Daniel Kahn on Radical Yiddish Autonomy, Bundism, and Productive Provocation

The singer-songwriter sits down with us at Yiddish New York to talk about his new album and what it means to sing in Yiddish today.

Daniel Kahn is among the most prevalent, prolific and acclaimed songwriters of the contemporary Yiddish and klezmer music scenes. He has been writing, performing and releasing music in many languages over the last 20 years. His original songs, covers and ‘tradaptations’ (his term for translated covers, reworked contextually to apply relevant lyrical content to their secondary language’s audience) are broadly historically informed and speak eloquently to a very wide array of leftist, Jewish and internationalist subjects. He has served as many leftists’ entrée into Yiddish, and many Yiddishists’ entrée into leftism. As such, his music serves as a sort of backdrop to the modern Bund revival with his brilliant, educational and entertaining body of work. Kahn sat down with Der Spekter contributor and DMV Bund organizer Abe Plaut at the Yiddish New York festival in December 2025 for the following interview, which has been edited for clarity.

– Aaron Bendich, Borscht Beat

Abe Plaut: Thanks for talking with me about music and Yiddish music and your album. To start things off, at Der Spekter, folks aren't so sure if they've seen or heard your thoughts about the Bund revival and the resurgence of Bundist politics, and so folks are curious to know what you think of it.

Daniel Kahn: It's a question of which Bund Revival and what we mean by revival. I feel like for many years I've been floating around the fringes of Bundist continuity. Folks who bridge the various generations and time periods.

I traveled to Melbourne and was lucky enough to perform for the folks down there together with Psoy Korolenko many years ago. That was nine years ago. I had the honor of knowing some of the last old Bundists in Tel Aviv, and I performed at the Bund Hoyz there and got to know Yitzhak Luden and folks from Warsaw who brought their particular Bundism even to Israel after the war and kept Yiddish left newspapers going there. [I also got to know] folks in this scene who brought the cultural yerushe (inheritance) of Bundism into their work and into their performances and were able to express their own politics. Through that connection, through that inheritance.

And in terms of the resurgence of, I guess we would call it “small b bundism,” like as a political or ideological orientation for folks relating to people's non-Zionism or anti-Zionism, their left Jewishness these days. I support it. I am of it, but I also need more. I think that there's a tendency towards a kind of reductionist, even fetishized sloganeering, which, it's cool, I have a lot of friends who wear doikayt patches and have various doikayt paraphernalia. It's a word that I talk about a lot, but I try not to be too reductionist in that sense.

Abe: What form do you think this Bundism, lowercase or uppercase, should take? Especially to try to build energy, to actually be a real movement for change?

Daniel: It can't be a movement for change in isolation. I believe that in terms of Bundism, a “small-b bundism,” has to do with strengthening the already existing and growing cultural movement for diasporic Jewish culture and language. I think that there were a number of movements within the Bund in the past that didn't put so much emphasis on Yiddish language and Yiddish cultural autonomy in the name of a more general, revolutionary class struggle … It's no longer a mass movement insofar as we're talking about folks who are [just] into Yiddish and socialism.

Yeah, there's a lot of us. It's big for a scene, for a niche, but it's not the kind of mass cultural or class politics which we had in interwar Poland. If anything, it's a kind of language of signifiers, and it's a way of anchoring ourselves in our work and connecting with each other within a historical framework and within a framework of values that inspire us in a contemporary positive sense, building up a robust culture of diasporic art and activism that engages in solidarity with other movements, with other Jewish movements and other non-Jewish movements and other communities. Which is a difficult thing to do without becoming... to resist isolation, to resist that kind of tribal... I'm getting very theoretical.

Abe: Yeah, it's one of the threads I'm gonna pull on a little bit and also then bring it to your music. You mentioned that this isn't like interwar Poland.

Daniel: It's interwar everywhere.

Abe: It's interwar everywhere.

I think there are some who might think that Yiddish song and also this type of Bundist politics is maybe a bit over-nostalgic, or that trying to bring new life is futile because of how much the actual conditions of day-to-day life have changed.

It's with some exceptions. Most Western Jews largely consider themselves to be integrated into their societies, not confined to insular communities. Clergy and employers don't hold the same kind of sway; it's just capitalists writ large. The actual conditions that turned the Bund into one of the most influential Jewish movements, those particular conditions don't exist right now.

Against that backdrop, can you tell us what you think the value is of writing, translating, and recording new Yiddish songs?

Daniel: I think that one of the characteristics of our condition is a kind of willful flattening of the past and a willful erasure of the diversity of Jewish cultural history and Jewish cultural politics. So for me, finding these old songs through the work of folks like Adrienne Cooper and Michael Alpert and folks in our community was like coming to a Jewishness that was explicitly kept from me. I did not grow up with this background. I didn't grow up knowing about the mass movements of workers in Yiddish, of those songs, of those struggles. I was not given that as a mode of Jewishness. I came to it through my other interests as a mode of Americanness because I was into the Wobblies, and I was into Woody Guthrie and the Civil Rights Movement, and it was like I came at it backwards.

I had to go back to it, and I remember how lonely it felt in my personal politics when faced with the kind of hegemony of mainstream Jewish political orthodoxy. And by orthodoxy, I don't mean religious orthodoxy, [but rather] political Zionist orthodoxy, and discovering this alternate history, which feels so niche and suppressed but was so robust and vibrant and global, was an incredible source of inspiration and strength for me as a person and as an artist.

We may not have a massive Jewish proletariat speaking Yiddish, certainly not, although there's something to be said for the fact that the Hasidic world is a working-class community, but that's not my world. [But] I was able to find a reflection of the world in which we live. I was able to find songs that addressed those eternal struggles against tyranny and poverty and exploitation and hypocrisy and unfreedom, and so for me it was a kind of very slow, natural process of finding this material and finding other folks in several different generations in this community and finding how that material had something to say to the world around me, living as a foreigner in Berlin for so long and trying to find the right tools as a performer to address the world around me. And I found those songs of struggles and migrations and humor and all of that and failure, epic failure. They had something to say to the world, to me.

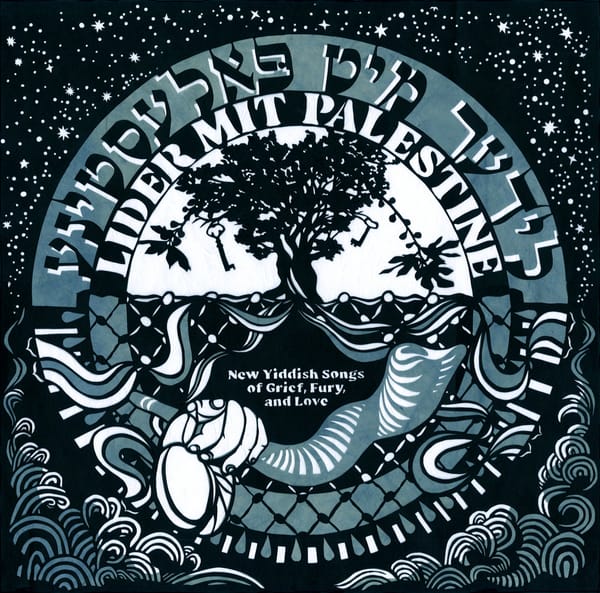

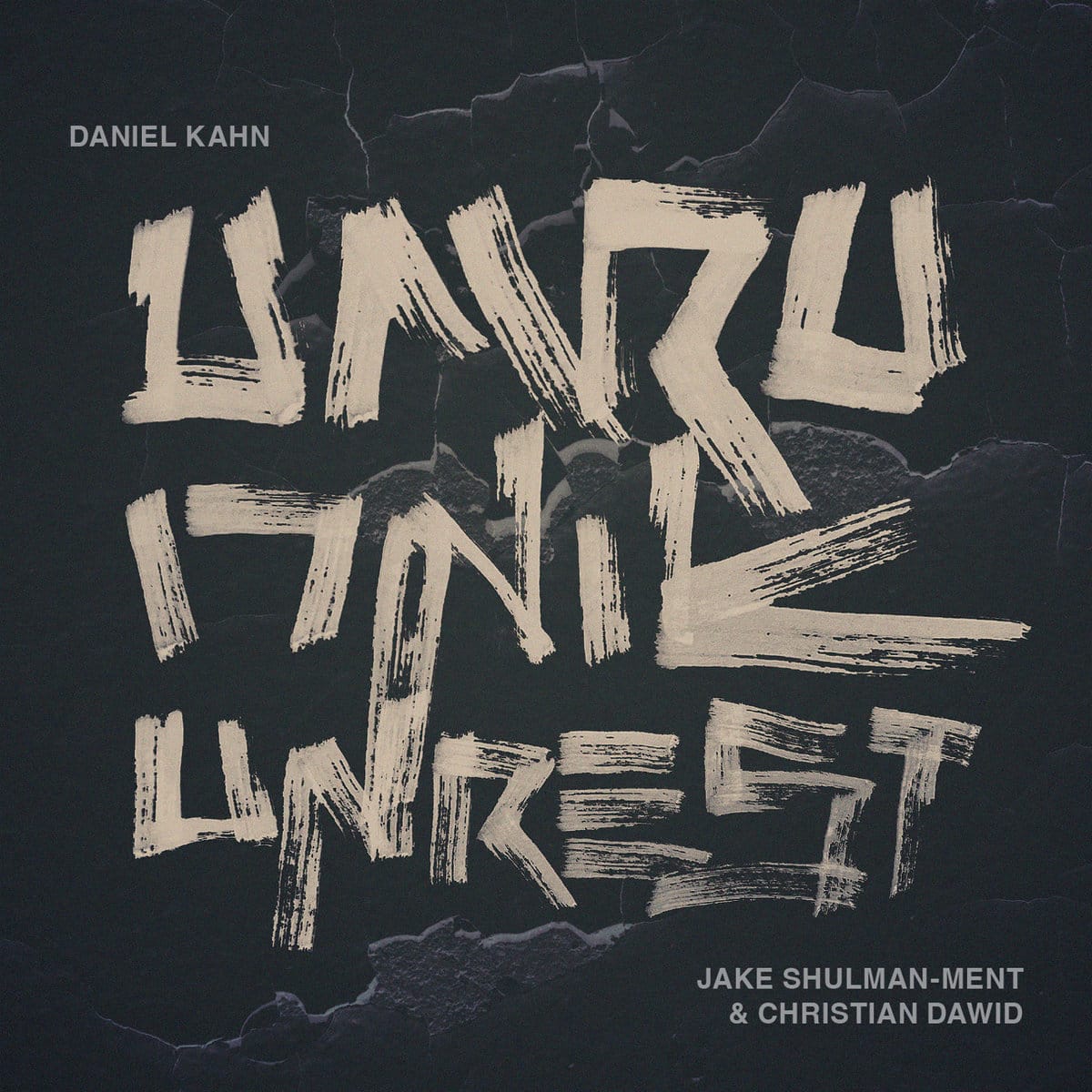

Abe Plaut: We're curious to know how “UMRU,” the new record, is a product of the current moment.

Daniel Kahn: We recorded it in 2024. So...it feels old. Yeah. The current moment feels [like] it's unbearably slow in arriving and departing. We're nowhere near halfway into the woods, it seems.

And on the record, there are songs which I had been working on and singing for a couple of years already. And the record itself is part of a trilogy of records that I made in this one studio starting in 2020. My solo record, “Word Beggar,” came out in [2021], and then Jake and I made “The Building and Other Songs” in ‘22, and that came out the next year. Then Jake and I and Christian Dawid had made this record in ‘24, [which] came out in ‘25. And all three of those records are very related. [In] this particular record, [and] the other records as well, [it’s about] the question of diaspora and exile and a multiplicity of allegiances and feelings of displacement and what I call the “displacement dichotomy.” If goles is about displacement, doikayt is about “this-placement.”

And that was almost a concept for the structure of this new record to have two sides: one being “nit heymish” (not homey) and the other one being “heymish” (homey). But certainly a song like “God Brother,” which is an old song of mine that I translated into Yiddish and then expanded, speaks to the current Cold War within the Jewish family, the deep seemingly intractable divisions within our communities. The question of Zion and nationalism and statehood and oppression and responsibility. And songs like “Nit Heymish,” the Georg Kreisler song, which is a kind of playful whirlwind of diasporic alienation, going everywhere and not feeling at home, only feeling at home in his old shtetl where now people look at him suspiciously and where we ask the question, who really loves that which they're not allowed to hate? Which I feel encapsulates a lot of the philosemitic alienation that we experience in certain contexts.

And then, some songs are really not about right now; they're about things that transcend the right now. Songs like “Proster Bronfn” is an old Yiddish folk tune/folk song and I wrote a new tune for it. Which is really just, the hearts of the bosses are cold as a stone. They think that the worker is something they own. This knows no moment, this dynamic. And like those other records, this record was just an opportunity to explore the various flavors of Yiddish. What it does to the meaning of a song by Tom Waits or Bonnie Prince Billy or Ewan MacColl — these are songs, which I know and love in other contexts — and to bring them into this context and into this language says something about what Yiddish can do, and it says something about what those songs mean.

Abe Plaut: The liner notes on the record said that UMRU was a call for radical Yiddish autonomy, a robust, independent Yiddish culture that stands transnationally against fascism and violence. Can you say more about that and what radical Yiddish autonomy means to you?

Daniel Kahn: It's maybe a bit of a clumsy way of making a slogan for what we're actually engaged in all the time in this community.

And to call for this autonomy, it's a tall order because, as a cultural community, we are in a particularly precarious position in our relationship to funding and institutional support in our relation to spaces in which our culture can thrive and grow. We're sitting here at an event (Yiddish New York) where you feel a very holistic sense of community and it takes a lot of work for that feeling to not just evaporate after five days because people go back to their various homes and their various countries. A lot of us live in places where there is no thriving context for our culture, for our language or for our politics. And we strengthen one another. This community really blossomed in the pandemic because it was already so interconnected and virtual most of the year. Then it wasn't about doikayt, it was about dortikayt (thereness), like we were all there somewhere else. And I don't know, who knows if this term has purchase or has legs as a radical Yiddish autonomy. Radical in the original sense of a radish, rooted to the root.

"[In] this particular record, [and] the other records as well, [it’s about] the question of diaspora and exile and a multiplicity of allegiances and feelings of displacement and what I call the 'displacement dichotomy.' If goles is about displacement, doikayt is about 'this-placement.'"

So I'm not talking about political extremism, but I am talking about a radical questioning of our political assumptions and our cultural assumptions, and that radicality is in the sense of us learning to support one another and ourselves in an institutional and positive, constructive way. And Yiddish in the sense of the language and the culture, but also in the sense that it's a mode of Jewishness, which is active and dynamic and progressive. It's both secular and spiritual and religious, and it's halakhic and it's [inclusive].

I don't want to create a position where it's about excluding cultural and political diversity within this community. That's not the point. I personally value the fact that there are people here with whom I agree about very little politically. I don't want to have to live under a hegemony of their opinions, which has been the case for decades. I don't want to feel like it's not a space where I can speak freely and openly about the questions and convictions that I have, but at the same time, I'm not about imposing a kind of orthodoxy of political thought that I agree with, which excludes other people. I do believe in the creation of spaces for encounter and productive conflict and dialogue. But what a lot of people don't realize is that for them to not be made uncomfortable by my feelings and opinions, we go back to an old model where my feelings and opinions and the feelings and opinions of a lot of folks are just silenced. And that's clearly not gonna be the case anymore, and a lot of people are losing their spaces and their work and their support because that can't be the case anymore, but the structures haven't changed. The funding hasn't changed. The donors haven't changed. The structural hegemony hasn't changed.

I'm not saying my idea, that spaces for progressive Yiddish culture are for open, progressive Yiddish culture, [can’t] be supported and be grown and be interconnected. The word “autonomy,” there's a long history of that word being used in different ways politically. We can all still fly to the Jewish Autonomous Oblast of Birobidzhan and not find much in the way of living Jewish culture, yet it is an autonomous Jewish zone, one of the only in the world. So that mode of autonomy is not necessarily what I'm talking about, but the kind of autonomy which grows out of connections and grows out of a community that supports itself and supports one another, and that has to do with our independence. Which isn't to say that we are unassociated with other institutional structures, but it would be nice to feel not so dependent on [them].

Abe: You hinted that the recordings for UMRU were made in June 2024 and that some of these songs were already in your repertoire. But I’m curious about how you landed at the songs that made the album. When did you start translating the newer translations? What was that process?

Daniel: The songs find me as much as I find them.

The beauty of working in this particular studio with these particular people ... it's the luxury of under-preparedness. With all three of these records I really went into the studio with some very loose arrangements of some songs that I had very recently translated or written or put together. There are a handful of songs that I've been playing for years. The 'For un Flie', which is part of this “Golus! Golus! Golus!” I've been doing that with Jake and with others for years and years, that's a Nazaroff tune. “Proster Bronfn” is a thing that I wrote 10 years ago. So you find sometimes it's like clearing out a drawer and finding a thing and you know you want to give it a home and you feel like it fits.

The Bonnie Prince Billy was a very fresh translation “'Nomadic Revery', 'Umetum.” I love Will Oldham as a songwriter I have for a long time. And there was something about that very weird song that I felt energetically and thematically related to the rest of the record in a very personal, almost psychosexual way, this theme of 'UMRU' and of constant motion and dynamism. I didn't want it to just be on the abstract political level. I want to talk about restlessness as much as I wanna talk about unrest and I feel like that song does that. “Nit Heymish,” the Georg Kreisler, I wanted to put that on the last record, but I was waiting for Isabel (Frey) to put it on her record because it’s her translation. And I feel like it fits with this stuff much better. And it was really fun to play.

“Dirty Old Town” I translated some years ago because I live in a harbor in an industrial zone of Hamburg and I love that song. “Time” by Tom Waits is just one of the best songs ever written. And when it opened up to being translated in Yiddish for me it was unexpected and I just love any excuse to put that in my set. So I love singing that song and I feel like it works in Yiddish. At least I hope it does.

We recorded a lot. We had a luxury of four days in the studio as opposed to the two that I had on the last two records. So we recorded a lot of other material as well, and in the end, we built the record that worked best as itself. But we also had a Quebecois song in Yiddish about the exile of Acadians being driven out of Canada [that didn’t make it onto the record].

We also have a German song on there that I've loved for many years, “Old Gray Highway.” I like expanding the theme to a broader cultural context. I like having those other languages there. There's a couple of songs of mine that are just my songs. I'm also still a songwriter. So I wanted to put one of mine on there, this song about a shipwreck (“Gone Aground”).

Abe: This next part of the conversation might get a little bit more music nerdy. But it's fascinating that you went in without so much really thoroughly arranged material. Especially because on “Nomadic Revelry,” with the violin entering on the first “Umetum” and then the poyk (drum) coming in, it's actually building in a way that the original record was just the same groove until that high intensity. It felt very thoughtful and intentional on those arrangements, and I guess there's a thought as a musician, surely that you're thinking about what you're doing.

Daniel: It is thoughtful and it is intentional. It's just not pre-planned. It's just the way those guys play and how we feel it. I have to give kudos to Will Oldham for his recording ethos also because I've actually heard him talk about the way he recorded that record. They worked out “I see a darkness,” I guess he did all those vocal overdubs in the middle of the night. So much of that song just had to do with the wacky freedom of the guitar player. We had to find the groove on that one 'cause we didn't want to play like post punk, rock on accordion and the violin. That one we did maybe three or four takes and that might have been the third. It grew. In the video you can see me reading the text off of my computer. I had never performed that song live before we recorded it. That's one that was really fresh. I remember translating it on the way down there to Stuttgart to, to the near Stuttgart and sending it to Asya Fruman, and she tweaked a few of the lines. It's a very weird song. It's weird in English.

I think of them like, not as jazz records, because we're not playing jazz, but I try to have the ethos of a jazz recorder of someone making a jazz session where the recording is not about some definitive, arranged, perfect version. There's nothing ideal about it. It's really about capturing the energy of a particular moment in a studio. It's about a particular performance. So in preparation, I made a Google Doc with one page per song, and the lyrics would be there, maybe I would have some notes about what the chord changes were. And somewhere else we had a spreadsheet of which instruments we want to have on which songs. But beyond that, there was no arrangement. It was all just by agreement.

Abe: On some of the tunes I heard what felt like a type of word painting, where the lyrics are a little bit self-referential to the music. It was with “Restless as a Wolf” or like this trio of klezmorim, and this is the trio record.

Daniel: Oh yeah, that's in the Halpern poem. We don't wanna be too literal about things. There's a bass in the drum to fiddle, right?

Abe: Or the bass clarinet maybe?

Daniel: Yeah, maybe. It's “Ikh bin der fidl, oykh dos paykl un der bas. Fun alte klezmer dray vos shpiln afn gas.” That's Moyshe Leyb Halpern, and that's a poem which I recited for a Halpern event that the Jewish Congress did in the pandemic years ago. And this poem just stuck with me. And then at some point I translated it and I tried to figure out how to set it. I had three or four different settings for it. And then at some point I just set it to this nign [Ashkenazi vocal melody] that Christian [Dawid] has shown us and we changed the rhythm. That song is a fever dream, too. Talk about a song about the dichotomies of identity, hereness, and thereness, and displacement. It's a haunted song — that song's got a specter.

Abe: So one of my colleagues or a fellow contributor at Der Spekter was thinking about how, not from this new record, but “The Jew in You” was like a favorite of your repertoire, especially because of how it inverts our people's social marginalization, flipping the particularity of our own experience. And it’s also a fun video. How does that song go over across different audiences?

Daniel: Oh, it goes over well. It’s long. I keep meaning to make a shorter version of it. Sometimes I'll break it up into two songs and put it into different parts of a set. It is a really effective way of addressing a topic without getting pinned down. I can't stress enough how playful and how much irony plays a role in this song.

I don't mean it as a kind of manifesto. It's got one tongue firmly in one cheek. But, at the same time, of course, it is a place where I deal with some important topics for me, and I think probably for a lot of other people, from what I've heard. Some of the lines that weren't even in the album version of it that I recorded in Israel on “The Fourth Unternational,” they're the last things that I wrote, and for me, they're somehow the most important to me:

“I grew up in a state where fate was something you could choose. While all around me, others were exploited and abused. My privileges were never noticed. They were only used. But history was haunting almost everything I knew and causing a division in the lessons that I drew.”

And that really is something that I haven't explored enough. The ways in which my particular take on Jewishness is entirely colored by my experience as an assimilated middle class white guy from America. That my position of privilege actually puts me in a very different place than a lot of Jewish folks in Europe, and my particular perspective is very much a component of my personal class and cultural background.

Abe: What is it like to be performing Yiddish songs in a place like Germany compared to like other places in Europe or the USA elsewhere?

"You're always gonna piss off somebody, and if you're not pissing off anybody, then you must be doing something wrong."

Daniel: It's hard for me to have any kind of comparison because I didn't really perform Yiddish songs before I was in Germany. Not as a focus. I arrived at the idea of performing Yiddish in Berlin in this community and in Berlin.

We could talk for another couple hours about shifts in the popular imaginary relationship to Jewishness in public in Germany in the last couple of years. That's a whole other topic that we really can't get into. It's very fraught. I feel like I've always been pretty good about being responsible for the terms on which I present myself. That's my luxury also as a singer because I can say whatever I want and I try to modulate the way in which certain things land. It's just a fact. People get less pissed off about something if you sing it, and you could accuse me of trying to be too diplomatic or too safe, but I also want to be effective as a performer, and I want to try to create, at least within the space of my performances, a mode of presenting ideas that when you just tweet about them, get just people acting insane.

I value spaces in which people are required to behave decently towards each other, and I do believe that you have a better chance of creating those kinds of spaces in cultural environments that are about expression. Nevertheless, you're always gonna piss off somebody, and if you're not pissing off anybody, then you must be doing something wrong.

Abe: Your music definitely doesn't shy away from politics, and my sense is that you frequently perform for more general Jewish audiences. Have political rifts in the Jewish community caused you to lose any opportunities, or create new opportunities?

Daniel: Yes. Certainly there are a handful of gigs where I could tell you, I didn't get that gig, or I lost that gig because of this, or that person who had this or that problem with this or that thing that I said or did. That has happened. I don't care. I need to eat and I have a family, et cetera, so the loss of work is no small thing. And we are dealing with a kind of de facto neo-McCarthyism, I think, in various contexts. And it's a very unfortunate thing.

At the same time, yes, there are certainly opportunities that I've had because of our communities and our movements. Mostly I don't know about the gigs that I wasn't offered. Which is a bliss, I don't want to know about the gigs I wasn't offered.

Abe: Related to that question, a colleague at Der Spekter saw Ira Khonen Temple and Michael Winograd, they were playing at the San Francisco JCC, like a West coast tour on Ira's new album, and they encored that performance with “Daloy Politsey,” which to this acquaintance who's in the audience thought that seemed like a little spicier for the generally older, whiter, wealthier, JCC audience members.

Daniel: The SF JCC is a little further to the left than most JCCs, which is saying very little, but I know good folks there.

Abe: How do those kinds of contradictions play out in your experience or in your audiences?

Daniel: I've been having those contradictions from the very beginning. We've had the power pulled out of our mics ... I believe in productive provocation. I believe that you can ask spicy questions and draw spicy comparisons and you can push certain buttons and I think that provoking people into questioning things can be a productive thing. And you can provoke one person and the person sitting next to them gets so offended that it shuts down everything and they just go into a rage. Ira is so fucking smart and Ira knows how to deal with this stuff and Ira knows how to take the right positions.

We played a Gaza benefit in Chicago a little over a year ago, and we all got so much shit we wanted to start a band called Traitor Jews, and I found the Trader Joe's font and made a little logo, it's one of my big unrealized projects. Ira gave an interview with Jewish Currents and they said something really smart, it was like, people who get upset about the choice of a word or, like singing something like 'Daloy Politsey', which, yeah, that's like calling for the like death of the Czar, and people who get upset at that kind of language in a song, they may just have a basic misunderstanding about art. Like what art is.

Singing a song is not the same as writing a resolution for some sort of an organization or writing an op-ed piece in a newspaper, or writing a pamphlet. Singing a song is a harnessing of invisible, ethereal, emotional ghosts. It's a harnessing of energies and humors. It's a kind of exorcising of our demons. We also sing murder ballads ... we sing really evil shit. We get shit out, and our relationship to the song is a very complex one. I have no love for Czar Nikolai. I also don't give a shit about Czar Nikolai, he's been dead for a hundred years. I'm interested in what that song says to us today about the current czars. And yes, let's say I'm gonna sing it about Vladimir Putin. I don't wish him anything ... a misa meshune, he should know a violent and miserable death. Does that mean that I'm gonna go and assassinate him? Or that I think that somebody listening to my song should? Not necessarily.

Somebody came up to me and Psoy once. We were playing in Russia, in a metal club in St. Petersburg and we were doing our Unternational material ... a Stalinist drinking song and a country song about Trotsky and all kinds of weird ideas and Zionist songs and anti-Zionist songs and, it was a kind of melange of ideologies, et cetera. And the sound guy came up to me after the show and he said, do you believe this, what you are singing, or is it art? And I didn't really know how to answer him, but I thought it was a great question.

I hope it's hard. I don't believe everything that I'm singing, but I believe in the singing of what I'm singing. Context matters. And as much as we are into Yiddish content, more importantly, I think we are into Yiddish context and creating contexts for these songs, which is, I think, even more important.

Abe: In an interview you did with another leading Dan in the Yiddish world on the Radiant Others Podcast, from that I understand, after studying theater and poetry — and you're in Ann Arbor, then to New Orleans — Patrick Ferrell, David Simmons, other accordionists encouraged you to go to KlezKanada. When and why did you land at the accordion though?

Daniel: Oh, that's interesting. I just gave a really banal interview about the accordion to the Jewish newspaper in Germany. They told me they're interviewing me in relation to the accordion, because I guess Germany has named it the instrument of the year for 2026.

So the accordion found me in a used guitar store in Ann Arbor in like 1997 or ‘98. Part of it was like my particular vibe, the songwriters I liked, being into Tom Waits and Nick Cave and Leonard Cohen, and for minor type of stuff. This was before I came to klezmer music. I bought that accordion, and I was also into New Orleans music, and I moved down there and I started playing accordion on the street. And, that's where I discovered klezmer music through friends like Patty and David and Michael Tuttle, with whom I played for 15 years in the Painted Bird. The accordion just became my travel companion.

"Our exchanges and contact between cultures is where culture flourishes the most, where it changes, on those nebulous borderlands ... Yiddish is itself a product of centuries of those exchanges that's baked into the structure of the language and the structure of those cultures and their migrations, and their multiplicities, and their intertextuality, their interlingual polyglot mess."

I think, coming up as a singer songwriter at that particular point in history of the late or the early 2000s, I felt like the world and I had reached peak acoustic guitar saturation, like playing open mic nights, there was a part of my brain that would just shut off when I saw or heard another white guy with an acoustic guitar. And this also came from playing in a lot of bars and a lot of coffee houses and a lot of clubs and a lot of streets where if you stand there playing an acoustic guitar, whether it's your song or Bob Dylan's song, people's eyes glaze over. This has been maxed out as a mode of social communication. And I found that standing there with an accordion, standing there with a ukulele, standing there with another type of instrument ... This was, in the depths of the indie folk alt country, pre-hipster, twee, like minimalist naval gazing poetry. It was very of its era — late nineties, early two thousands. I don't know, the accordion just went with me and it was my entreé into this community.

When I first went to KlezKanada, I was not into the Yiddish language. I was not into the songs. I was into the music, I was into klezmer, and I just wanted to study klezmer. I wanted to learn how to play this dance music and I wanted to get into my instrument in a new and deep way. I was doing that and then hearing folks like Michael Alpert and Adrienne Cooper really knocked me on my ass. I thought, oh, there's something to be done in this language. And it's no accident that I play an instrument that you can sing with. I'm not gonna be a trumpeter. You can't sing and play trumpet.

Abe: In what ways do you think accordion feels connected to the music of social movements? It feels not just like “guy with guitar” in the same way.

Daniel: “Guy with guitar” is pretty connected to social movements. The one time I made a riot cop laugh was at the RNC protests here in New York in 2004, when Bush was being reelected and there were huge demonstrations. I don't know if people remember the kinds of mass mobilization that went on around the Iraq war and around 2003, 2004. But I remember being down on the street, I guess it was on Sixth Avenue or something, and just an ocean of riot cops come storming by, and shit hadn't gotten really hot yet, but I was there with a bunch of folks and as soon as they came marching by, I started playing Imperial March (from Star Wars) on my accordion, and I caught a couple of them laughing, I made a storm trooper laugh.

Yeah, having an accordion on protests can be a robust physical protector. I don't know if it'll stop a bullet, but it might take a hit for you. That hasn't come to pass for me, thank God, because I wouldn't want anything to happen to my accordion. You probably shouldn't go to a protest with your best accordion. Accordions are alive. It's not a keyboard, it's a wind instrument. It breathes. It's one of the only instruments where there's a whole button that can just make it breathe. People used to think it had spirits in it. The idea that simply by letting air pass through a tube or over a little reed, that would make it sing, that this was an invitation to the evil spirits. In many ways the church organ was a kind of domestication of that. That it was a way of boxing up the devil and keeping it in the church, and the accordion lets the devil out again. I like that.

Abe Plaut: Lastly I'm just curious how you relate to other kinds of diasporic musical cultures, and maybe to bring it to the accordion specifically. Cumbia, mythically, is a product of self liberated Afro-Colombians who stumble on accordions from a washed up German ship.

Daniel Kahn: Yeah. The role of the accordion in Colombian music and all over the place. It's a real global instrument. And the bandoneón and the concertina, it's a seafaring instrument. In German, they call it a schifferklavier, a sailor's piano or a chest organ, or a quetschkommode, which literally means squeeze box.

But I like it in terms of kvetching, and it being a commode for my kvetches. The relationship of Yiddish diasporic culture to other diasporic cultures is a particularly interesting thing to me. A lot of this has to do with Berlin, so the ability to have music and theater projects, which bring Yiddish language and Yiddish music and history and perspectives into conversation with folks who are bringing Turkish diasporic culture, Palestinian diasporic culture, Brazilian and Irish and certainly post-Soviet culture where one could say that a certain type of Russian language culture exists in diaspora in a way in which it cannot exist within Russia, and that which is also of course related to Yiddishkayt.

Our exchanges and contact between cultures is where culture flourishes the most, where it changes, on those nebulous borderlands. That's how culture develops. That's how culture survives. That's how traditions survive: through mutation, through encounter, through exchange. Yiddish is not only very good at those types of exchanges. Yiddish is itself a product of centuries of those exchanges that's baked into the structure of the language and the structure of those cultures and their migrations, and their multiplicities, and their intertextuality, their interlingual polyglot mess. It's always a messy thing. And those borders — clear cut borders do not exist.

And Yiddish is ... I don't wanna idealize and say that it's all about openness and outwardness. Certainly this is a language of a culture, which is a lot about separation and isolationism, and havdole (havdalah), like drawing various and strong borders within the language, within the philosophy, within the theology, within the culture. But even those tendencies come up against radical universalism and solidarity and revolution and other goals, other values. And that tension there is also a productive one, I think.