For a Bundist Chanukah (the Best-Worst Jewish Holiday)

We can think of the struggles that might have been left out of history, so that new struggles can make history today.

Chanukah is, ritually speaking, the best Jewish holiday. Fried food, open flames, gambling games, sometimes even presents. That makes it all the more painful that, from the perspective of political theology, it might be the worst. Or it might not. It’s complicated.

It’s complicated because there are at least two Chanukahs, a story known by all and a history it would be nice to forget.

The story of Chanukah denounces an emperor who, in his lust for power, suppressed religious freedom and forced his gods on the Jews. It celebrates a band of partisans who, against terrible odds, waged heroic battle, triumphed, preserved the Jewish people and set a precedent for all peoples to worship as they wish. The mystical miracle of the lamp that burned for eight nights represents the military miracle of the liberation, which was impossibly won. This is a festival of cultural autonomy and of the miracle that all hope needs. Its burning candles remind us that in politics, if not in physics, miracles really do happen.

This story is stitched together from selective memories. Another Chanukah emerges from the unselected and often forgotten moments of its history. Which is possible because Chanukah, unlike most other Jewish holidays, is based on historic events recounted by annoyingly reliable sources. If we can know something of what really happened, are we permitted to ignore it in favor of better stories?

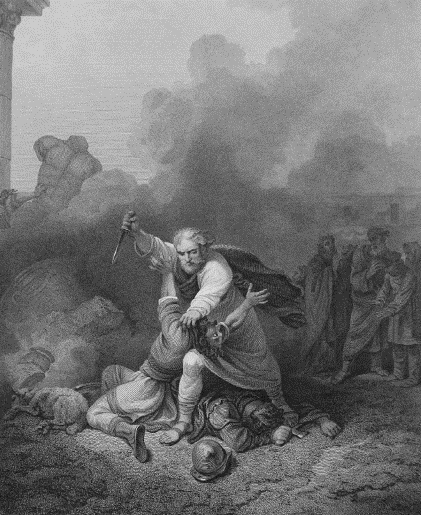

On the 25th of Kislev 3598 (164 BCE), when the insurgent Maccabees consummated their liberation of Jerusalem by rededicating the defiled Temple, they were emerging victorious from what most scholars believe began as a civil war among Judeans. On one side: the cosmopolitan, Hellenizing strata who were then spreading out along the Mediterranean coast, worshipping the Israelite God but also developing an appreciation for speculative philosophy and muscular sculpture, exercising naked in public gymnasia, tolerating the worship of Olympian gods in their midst, accepting the suzerainty of faraway rulers, and ignoring the poverty of the uneducated masses. On the other side were Aramaic-speaking laborers in the cities and cultivators of the rocky land, attached to their Semitic language and their ancient rites, bristling under the power of empire and appalled by fashionable urban culture and classy foreigners strutting along their cities’ streets.

It’s impossible to say with precision whose provocations really triggered the conflict; while 2 Maccabees emphasizes the inept exploitation of Judea by the imperial rulers (either at the behest of many Hellenized Jews, or with their passive acceptance), 1 Maccabees tells of charismatic traditionalist leaders who fomented righteous terror against their cosmopolitan countrymen, calling them blasphemers and renegades who “hated their own people” (1 Mac. 11:24). Eventually, the emperor Antiochus IV intervened on the side of the Hellenized Judeans, aiming to destroy the power base of the pious insurgents, and the civil war among Judeans increasingly became a war of Jewish liberators against Greek oppressors.

Does it sound familiar? Progressive liberal elites and mobile middle classes pitted against resentful lower classes and traditional families; lovers of diversity-within-empire against inward-looking xenophobes; enthusiasts of hegemonic culture against national separatists. On one side, those who would protect Jewish tradition by reducing it to private worship and making sure it doesn’t challenge anyone’s power or way of life. On the other side, those who would protect Jewish tradition by making it the all-encompassing ideology of a definitively Jewish and independent state. The victory commemorated by Chanukah was won by national-conservatives over proto-liberal assimilationists. The radical Diasporist position is left out of the story.

But Diasporism, by that time, already had a long heritage. When the canonical form of the Bible was compiled in the wake of the Assyrian and Babylonian deportations of Israelite populations, the notion of exile was taken beyond history and made into a myth of humanity exiled from paradise. After Babylon gave way to Persia, and the Temple was rebuilt under this new foreign sovereign, Exile became a condition of Jewish life everywhere. After Alexander conquered Persia, Jews entered a new period of “Greek exile” without needing to move a cubit from where they were — as under Persian rule, they weren’t forced to leave their homes, and they were allowed to freely settle in the territory that was sometimes called “Israel.” But Jewish life thrived in places like Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria.

Hellenizing Jews began translating the Bible into Greek, and through a clever mistranslation of Deuteronomy 28:25, they transformed the negative concept of Exile into dialectical conception of diaspora. God had declared that if the Israelites disobeyed Him, they would “become a horror to all the kingdoms of the earth”; or so thought the Deuteronomist historians. But in the Hellenizers’ words, God said, “you will become a diaspora,” a scattering of seeds. The horror of being a foreign element in someone else’s land became a moment in a process of travel and growth. For the Deuteronomist historians, the following verse (Deut. 28:26) had been meant to emphasize this horror: “Your carcasses shall become food for all the birds of the sky and all the beasts of the earth.” But if we are a diaspora, then our carcasses are seeds.

The ideas were there, but as so often happens, the proto-liberals only pursued them halfway. They embraced Diaspora but also empire. They built a Temple of Diaspora in Alexandria to rival the Temple in Jerusalem, but it was a temple of elegance and international high culture, not a refuge for the outcasts of the earth. The imagining of a Diaspora that fought for cultural autonomy and equality among all peoples and strata—an idea that had already begun to take shape in prophetic and apocalyptic writing—was held in check by the Hellenizers’ acceptance of cultural hierarchies and by their failure (as far as historical evidence reveals) to address the grievances of the poor.

It was the national-conservatives who rose up — first against their moderate coreligionists, and then against the empire that supported the moderates and ended up alienating the entire Judean population. The Maccabees, thanks to their organizing skills and decisive action, forced the political scene to divide along terms set by them. In the ensuing battles, there was no autonomist-socialist party to support, at least none powerful enough to make it into the historical record. Then, as now, it was the conservatives who drew the battle lines and took the leading role in a fight they picked. Then, as now, our position was left out.

But that was history, and holidays are about stories, not history.

We can tell a story of Chanukah as a victory of militant separatism — and it was this story, the founding myth of the Hasmonean dynasty (140–37 BCE), that the early rabbis declined to include in the definitive canon of the Hebrew Bible. Looking back on the revolt after independent Judea’s defeat and Rome’s eventual destruction of the Temple, they were trying to construct a kind of Jewishishness that could survive without a Judean kingdom, and without rulers whose only claim on power was their military prowess. (It wasn’t until the modern moment of renewed separatist militancy that the holiday gained its contemporary importance.)

We can also retell the story as the Prague Maharal did, when in his book Ner Mitzvah (written ca. 1590–1600) he reinterpreted this war of one nation’s liberation as a war against all earthly empires, which represent the “lack” or imperfection of the world. The true unity of the world will only come with the arrival of the Messiah; then the empires’ “rulership ends, so the world will indeed become complete.” In the meantime, it is up to “Israel” to show that it has “merit” by showing that the rule of its overlords is incomplete.

We can also tell a story of Chanukah as a reminder that unless we fight for it, our position will be left out. The historical victors were conservative particularists, but the story also transcends history. The Maccabees won a battle fought with iron, but when they came to the Temple, a miracle entered the memory of events. When they crossed into sacred space, history became story and the particular became universal. A struggle won by some people and lost by others became remembered as a symbol of struggle as such. We can acknowledge the courage of those who fought for dubious causes, if it reminds us to fight for something better.

We can think of the struggles that might have been left out of history, so that new struggles can make history today. For the two centuries after the Maccabean Revolt, Judean society was a hotbed of competing sects, defenders of popular worship and of priestly privilege, imperial lackeys and fighters for cultural autonomy, zealots and political assassins and dispassionate bookworms, communalists and hermits and street agitators, reformers and propagandists of the deed and social revolutionaries, communities of converts and farmers and freed slaves. No one can prove there were no Bundists avant la lettre among them. We can celebrate the Bundists who should have been there and now can be here.

We can give new content to the celebration of struggle, to make the struggle our own. We might be weak now, but the history of struggle is a history of astonishment, of events as unexpected as miracles.