How traditional Jewish grief ritual can serve us as radicals

I couldn't find Jewish grief resources that reflected my values, so I created my own.

The day my mom Deborah died in 2024, someone gave me a popular book on Jewish grief. Like most resources on Jewish grief, it was normatively masculine and heteronormative. The tome included a large section on whether women’s voices were too holy to participate (yikes).

But I desperately needed a resource that would instruct me about Jewish grief and what was expected of me. My friends and loved ones needed one too.

Thus, my graphic novel, “The Jewish Weirdo’s Guide to Grief,” was born.

In writing my book, I took inspiration from a long line of Jewish graphic novelists and cartoonists – Stan Lee and Art Spiegelman are two notable examples. The medium of cartooning has long helped us when words fail — especially when confronting difficult or subversive topics. Spiegelman’s "Maus," for example, recounts a chilling Holocaust grief story through comics.

My social justice sensibilities – solidarity, Jewish anti-Zionism, doikayt, queer values – are reflected in my book, which exists to challenge gender-normative assumptions around Judaism and grief. Traditional Jewish grief ritual, when freed to be expansive and inclusive, moves us to an insistent close-knittedness. Such ritual guides us weirdos in how to show up for each other in times of need.

Who is a Jewish weirdo? I claim this term for everyone like me who draws from the margins toward the middle, who enjoys inclusive Judaism.

"Traditional Jewish grief ritual, when freed to be expansive and inclusive, moves us to an insistent close-knittedness. Such ritual guides us weirdos in how to show up for each other in times of need."

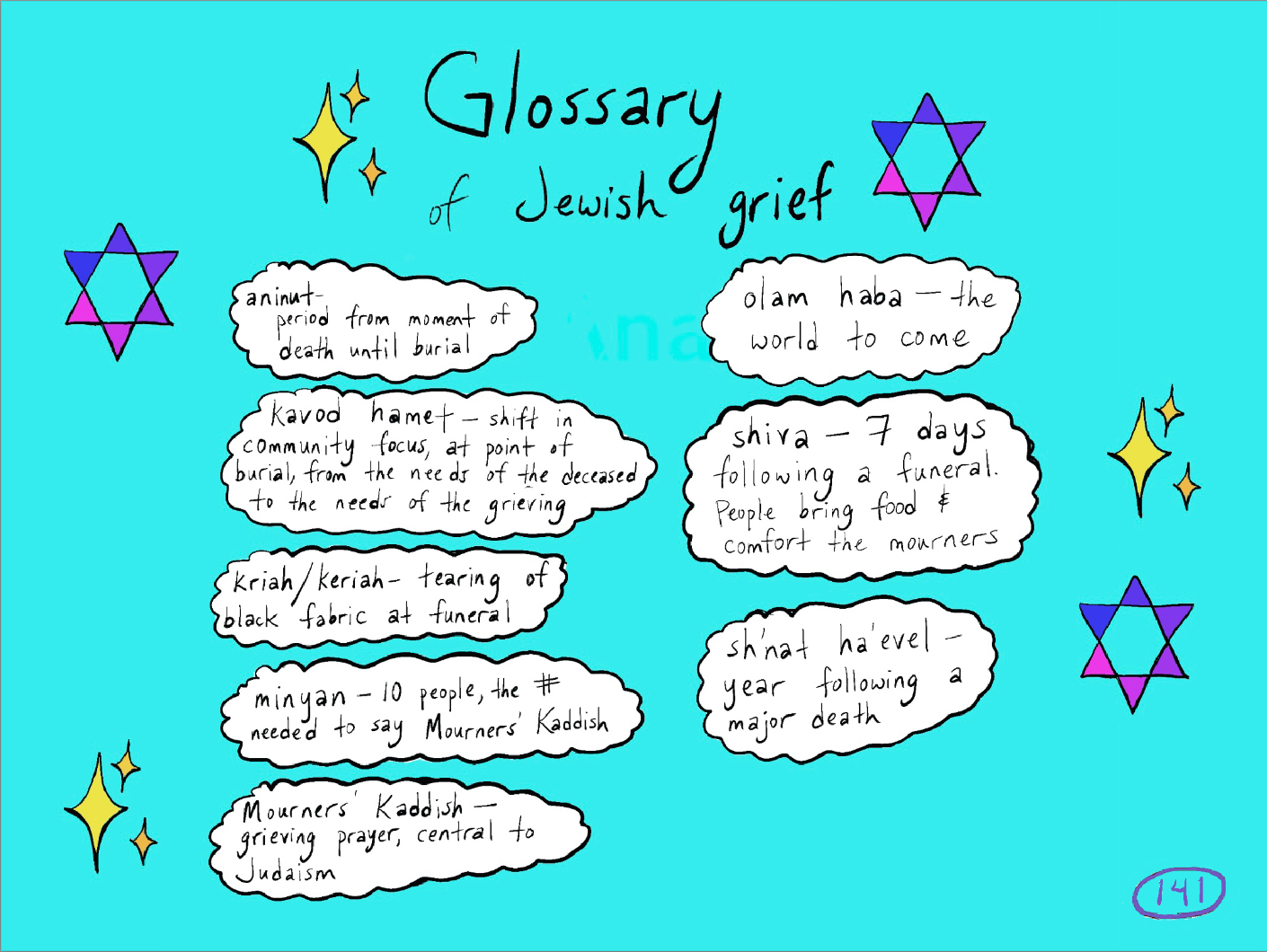

My friends and loved ones, who wanted to be supportive during the aninut (period of time between death and burial), shiva, and beyond, needed such a resource too. If you’re a leftist, Jewish or not, who wants to help someone grieve Jewishly, you’re enough of a Jewish weirdo for me.

Grief, publicly and privately displayed, is an indelible aspect of social justice. I spent a lot of the last few years as a Black Lives Matter organizer and activist in Washington, D.C. We come together for hip-hop dance parties in the street that often include grieving young Black people who have been murdered by the police.

Public displays of unimaginable loss and pain have a long American activist history. Emmett Till’s mother chose to display him publicly at his funeral, thereby galvanizing the civil rights movement.

In times of loss, Judaism has very clear ancient scripts for us to follow.

Shiva practice instructs us to stay close to each other for the first seven days of grief. “Show up and give them silence,” an ancient Jewish precept about shiva, is one of my personal favorites.

In the midst of grief, there may simply be nothing you can say. You can sit next to the griever and look into the crater where their life used to be.

We have to take care of each other, especially now. Our collective grief and hurt here in the D.C. area over intensified policing, ICE raids on our friends and neighbors, and general fascist oppression in our town is acute and can feel never-ending. This is the time to move toward each other in our collective grief.

The "Jewish Weirdo’s Guide to Grief" ebook is available at jewishweirdosguide.com. To support this project and get a physical copy on your bookshelf, email the author at recovery.chana@gmail.com to donate to the upcoming Kickstarter.