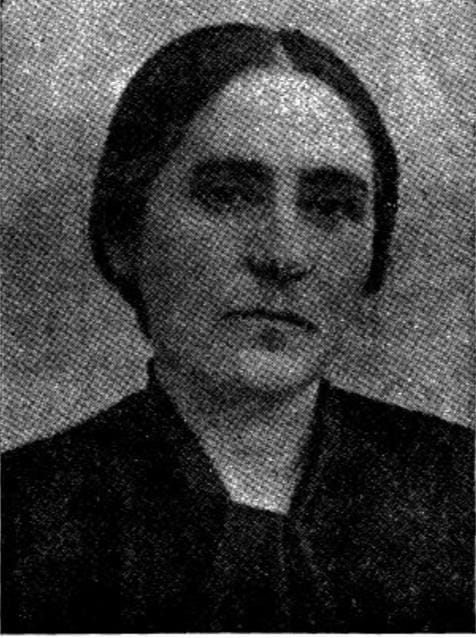

Introducing The ‘Tuers’: Translations from Doyres Bundistn, Part 3: Anne Braude-Heller

The doctor-activist is often publicly remembered for her heroism in the Warsaw Ghetto, and less for her political activity with the Bund before 1940.

This is part 3 of an ongoing translation series from Doyres Bunditsn, biographies of Bundist 'tuers' or 'doers.' The Introduction/Part 1 and part 2 of the series are available on our website.

Anna Braude-Heller – activist, doctor, scientist. In historiography, she is primarily associated with her activities in the Warsaw Ghetto, while little is said about her pre-war activities. Although the shift towards women's history and the work related to the development of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum (located in the building of the hospital to which she devoted her entire life) are changing this situation, we still have to ask ourselves why such an important figure, in the popular imagination, was for so many years merely a backdrop to the history of the struggle of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters. This entry from “Doyres Bundistn,” translated below by Sam Miller Hirshberg, is one of the few examples of Anne Braude-Heller's inclusion in the “pantheon” of Bund heroes.

Dr. Anne Braude-Heller was born in Warsaw on 6 January, 1888 as Chana Rywka Braude. While studying medicine in Zurich, she joined the Bund. She then moved to Berlin and Saint Petersburg, where she obtained her medical licence. She returned to Warsaw in 1913 and shortly before the First World War, she began working at the Bersohn and Bauman Children's Hospital. In 1915, she co-founded the Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Dzieci (Society of Friends of Children). She was also a co-founder of a school for paediatric nurses. In the context of the history of the Bund, however, the most interesting fact may be that she was a co-founder of the Włodzimierz Medem Sanatorium for Children and Youth in Miedzeszyn, which was made famous by Aleksander Ford's film “Mir Kumen On,” and a Warsaw councillor. She was also a physician for the Central Yiddish School Organization (TSYSHO).

In 1923, the Bersohn and Bauman Children's Hospital was closed for financial reasons. But thanks to Braude-Heller's fundraising activities, the hospital was not only reopened, but expanded under the auspices of the Towarszystwo Przyjaciół Dzieci becoming one of the most modern facilities of its kind in Warsaw. From 1928, Braude-Heller served as chief physician and head of the infant ward. As a result she is referred to as ‘Naczelna’ (Chief) in memoirs.

Her private life was marked by tragedy. In 1926, her son, Olo Heller, died at age of 5, after she failed to diagnose his appendicitis, despite her experience. In 1934, her husband, Elizer, also died.

After the ghetto borders were closed in November 1940, the hospital found itself inside. Braude-Heller and her team cared for thousands of young patients. Many of them, as her colleague Adina Blady-Szwajger recalled, came to the hospital only to be able to die in warmth, surrounded by people, and not alone on the street. After the so-called Grossaktion Warschau (the largest wave of deportations to the Treblinka extermination camp) in the summer of 1942 and the liquidation of the so-called Small Ghetto (the southern part of the Warsaw ghetto, where wealthier people lived and where the hospital was located), the hospital was moved to a branch location that had existed since October 1941, located at the corner of Żelazna Street and Leszno Street. From there, it was later moved to Stawki Street.

During the existence of the ghetto, Braude-Heller headed the Health Commission at the Warsaw Judenrat and conducted underground teaching in the ghetto. As Blady-Szwajger recalls, she was also the originator of the “Matronat,” (patronage) under which she instructed her employees to persuade well-off Jewish women to donate funds to the hospital.

The exact circumstances of her death are unknown, but she likely died with the rest of the staff and patients in the bunker at 6 Gęsia Street in April 1943 in unknown circumstances. In her post-war testimony, her sister Judyta Braude expressed the hope that Anna committed suicide using the bottle of potassium cyanide she was supposed to have had with her. Dr Polisiuk, her coworker, gives a slightly different version: he believes that Braude-Heller was in a group that left the shelter on Gęsia Street and, together with others, looked for another hiding place. However, Polisiuk does not know what happened to her afterwards. He saw her for the last time in May 1943. The author himself probably died on the “Aryan” side. Written in June 1943, the account was part of the underground movement's archives.

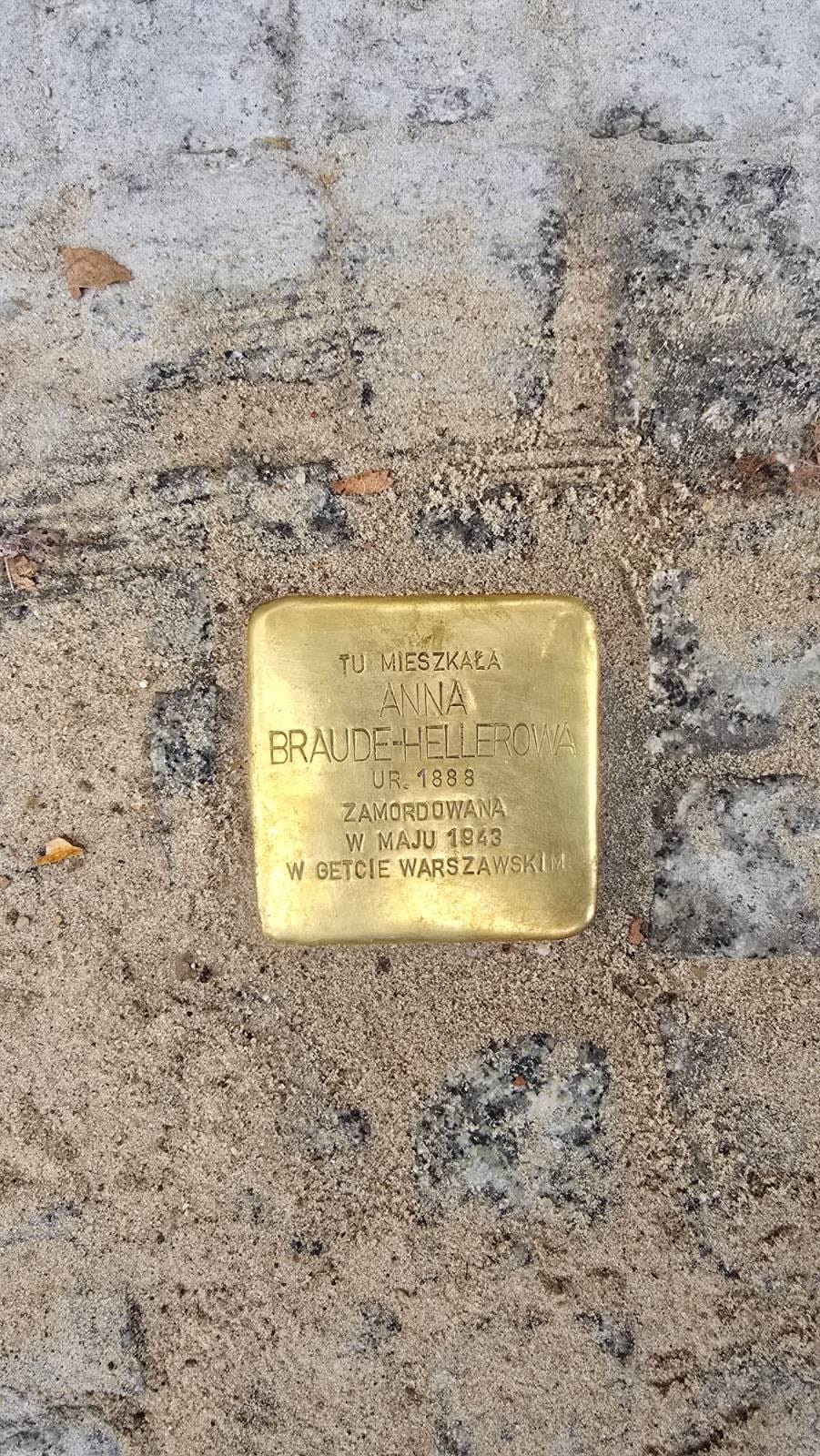

Anna Braude-Heller’s Stolpersteine in Warsaw. Image courtesy Ewa Nowakowska.

The symbolic gravestone and the Stolpersteine on Szpitalna Street 5 (the last address where Anna Braude-Heller lived before being moved to the ghetto) are the only permanent memorials to this remarkable figure. On the anniversary of the outbreak of the ghetto uprising in Warsaw in 2022, a mural commemorating 13 figures important to the history of the ghetto by artist Adam Walas was inaugurated. Among them was Anna Braude-Heller. Currently, the hospital building is being converted into the headquarters of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum. Its mission is, among other things, to popularise Braude-Heller’s story. However, there is still a lack of permanent memorials focusing on Braude-Heller's activities before 1940.

In fact, she is rarely mentioned in the context of the history of the Bund. We must ask ourselves why this is the case: Is it a result of the human tendency to commemorate martyrdom rather than heroic lives? Is it the result of neglect in researching Bundist herstory? Reading Doyres Bundistn, we can see that many women are mentioned in the context of their distinguished husbands and sons, as those who nurtured altruism in them. Following the biographies of Bundist female activists in the interwar period, we see that many of them (despite the declared equality in the party) were reduced to the role of rank-and-file activists who could only rise in the hierarchical structure in typically ‘female’ fields such as medicine or education. However, many of them remain anonymous. Perhaps this points to the need for more in-depth research into the history of these areas of activism.

That is why the following translation is so important. It is not only a reminder of the activities of activist Sofia Dubnow-Erlich (the author of Braude-Heller’s entry), but also of the biography of Anna Braude-Heller, which is constantly being rediscovered.

— Monika Nestorowicz

Dr. Anne Braude-Heller

Looking back, I see before myself a petite figure, her pitch black hair split with an even part, large shining dark eyes, shaded by long eyelashes. How many times did I watch her eyes strain — concentrating, scrutinizing a childish face reddened from fever… in those moments not just painful distress lived in her, but also an obstinate effort of will which was prepared to fight to hold that weak life in that small body in spite of everything and everyone, as only mothers can, as we never lay down our arms.

Anne Heller had already selected her profession in her youth. A daughter of a well-to-do Warsaw manufacturing businessman with the name Braude, she traveled abroad after finishing Gymnasium to study medicine, and dedicated herself to university work in Zurich and Berlin with diligence. Parallel with her profound interest in science, she began to realize that a good doctor could not avoid being a social activist. The young student became a socialist, an eager attendee of speeches and discussion-assemblies.

Brought up in the thicket of the Jewish quarter, in an environment where assimilation was foreign, she unwaveringly aligned herself with the Jewish labor movement. In 1914 she was arrested at a secret meeting. The young doctor was active in the Bund, especially during the First World War, when she would appear with lectures and speeches before great assemblies of Jewish workers. Together with her husband, engineer Eliezar Heller, a Bundist tuer since the time of the Tsar, she took an active part in Bundist cultural work. Later Anne’s social activity was not confined purely to party activities, as she maintained in actuality her association with the Bund as well as personal friendships with many of its tuers until the end of her life.

Already in the first years of her activities in Warsaw, Anne Heller became popular not only as a doctor of outstanding intuition and a warm motherly heart, but also as a talented organizer. Her favorite arena was the establishment of public medicine — hospitals, nurseries, consultation stalls, and child sanatoriums. At first she was dedicated to the popular children's institution Tropn Milkh [Drop of Milk], and then later the famous child sanatorium named for Vladimir Medem in Myedzeshin or some other institution — everywhere she served with insight and action.

In her last years she served as the head of a famous Jewish children’s hospital in Warsaw, a position which in the days of the German occupation became a dangerous fighting-position. She worked feverishly, drowning her undying pain for her lost tiny son in worry for the children of strangers. At that hospital on Śliska street people used to bring children together not only from all corners of Warsaw, but also from all the surrounding cities and small towns. The energy, self-sacrifice, and ardor of the head doctor infected the entire staff from top to bottom, and the anxious mothers of the poor capital streets as well as from other cities looked with hope at that great white house, where day and night a blazing struggle raged for the life of their children.

The hospital took top priority for Dr. Braude-Heller even during peacetime, but in the days of the siege of Warsaw it became her home. Throughout the night she personally stood watch at the beds of the children, and when artillery bombardment started fires, she together with her sisters transported the children from one burning building to another. Through the rustling and rumbling of falling bricks her steady voice rang out and her courage and self-assuredness was able to lift up even the most shocked and frightened.

The day-in, day-out fighting with people who had lost any mask of humanity proved to be much harder than fighting with the elements. In the first days of the Nazi occupation the sadist who stood at the head of the Medicine Office fought against the mothers of hundreds of children. Anne Heller refused to back down: When patients with a high temperature were taken and led into barracks for infectious diseases, she made an effort to save them through both truths and deceptions, dictating forged reports and hiding the most sick during surprise inspections. Once, she alone decided to enter the den of the beasts — the chief medical committee — in order to admonish the arbitrariness and cruelty of the office. A roaring satrap expelled her from the meeting with vulgar diatribes and the guard threw her through the door with a kick. White as chalk, lips tightly pressed together, she returned to the hospital and silently locked herself in her room, but when the time to examine the sick came she went out with a strong stride and went to undertake her usual duties.

The famous scholar Professor Ludvik Hirshfeld, who worked together with her in the Ghetto, later in his book The History of a Life [Di geshikhte fun a lebn] characterized her thusly: “Dr. Heller had reorganized the children’s hospital before the war. She was an admirable, thoughtful doctor and the embodiment of energy. Her wise voice and manner of speaking evoked many emotions in those that heard her.”

The indefatigable Anne worked, researched, and fought. After the Second World War a work of hers from 1942 was published–The Clinical Picture of Hunger in Children– in the collection Hunger-Illnesses [Hunger-krankheytn] which the Joint [Distribution Committee] published in 1946 in Warsaw.

The body count among the children grew each day. The fight with the brutal powers that be became hopeless. A female colleague of hers later wrote of her: “The head doctor of the hospital died a little with each child who her stubborn efforts were unable to save from death.” Friends wanted to take her to the “Aryan” side — she refused them. I still have work to do among the remaining Jews in the Ghetto, she answered.

We know little about her last days. But what we know speaks volumes: she was a ‘field-doctor’ in the Jewish-German Ghetto battle, in Spring of 1943. Together with the Ghetto fighters she died at her post, under the ruins of the last Jewish hospital on Gęsia street. Dr. Anne Braude-Heller was killed together with that Jewish Warsaw in which she was raised and where she knew every stone and crack in the pavement and to whose children she gave her life.