Organized Labor, Politics and Klezmer Musicians in New York Until the First World War

From the early days of the 1880s to the First World War, klezmorim were present at every twist and turn of immigrant Jewish radicalism and labor organizing, from strikes to union elections.

When klezmer musicians began arriving in New York City in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they experienced a deep culture shock similar to that of many of their fellow Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Although some had worked in cities in Europe, many of them went from being apprentices in family klezmer bands in villages to musicians for hire in a dense urban environment.

Klezmorim were one of the many traditional occupations that came to America with the waves of Jews from Central Europe – among them also rabbis, barbers, silk weavers, and shtetl inn keepers – and had to adjust to urban life. Some of these musicians continued to play Jewish weddings and communal events as they had in their previous lives, while others joined Yiddish theatre orchestras or played in restaurants and vaudeville halls. Some went respectable and joined classical orchestras or military brass bands, while others left the music industry as soon as they could.

These klezmorim also made up a small yet important part of the story of socialist politics and labor organizing in New York City. Like most people in history, few of them wrote anything down about their lives, and they did not receive much attention in the press. But what we do know is that these musicians joined unions and supported political movements. Their music accompanied strikes and marches before and after the turn of the twentieth century and empowered immigrant Jewish workers to feel like human beings again through dance and socialization.

Information about the lives of the earliest New York klezmorim is scarce and we can only piece it together through newspaper clippings, fictional portrayals and so on. Most likely, not very many klezmorim were in New York before the 1880s, even though the profession had a long history in Europe. By 1889, enough klezmorim had arrived in New York to organize a labor union, the Russian Progressive Musical Union No. 1, under the newly formed United Hebrew Trades, which had also organized cap makers, shirt makers, Jewish actors, typesetters and many other trades. The musicians’ union had about a hundred members after two years and continued to grow in the following years. Advertisements and articles in early Yiddish socialist papers such as the Arbeiter Zeitung and the Folksadvokat are plentiful; they organized concerts and played at picket lines and union marches, as well as more traditional settings like weddings and banquets.

Left: Flag of the United Hebrew Trades of the state of New York, presented in Anu Museum Tel Aviv via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Street scene on the East Side, New York, circa 1910. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Klezmorim continued to arrive from Europe in ever greater numbers in the 1890s. Among them was Wolff N. Kostakowsky (1879-1944), a violinist from Crimea who arrived in 1892 and worked as a music teacher, wedding musician, and composer. In 1916, he published the tunebook International Hebrew Wedding Music. Another was Abe Katzman (1868-1942), also a violinist, who arrived from Chișinău in 1897. He co-founded the Kishinever Sick Benevolent Society, a mutual aid society for immigrants from that city, primarily to help refugees who were fleeing the Kishinev pogrom of 1903. Like many klezmorim in New York, he developed a longstanding professional relationship playing for immigrants from his home region. (You can listen to some of his 1928 recordings here.)

The 1890s, and especially the early 1900s, saw the formation of thousands of mutual aid societies like Katzman’s Kishenever society. These societies offered benefits like sick pay and burial plots. The most common type, which was based around the town or region of origin of their members, was also known as landsmanshaftn. Others were organized around a family or religious congregation, or around a charismatic figure or trade. Many combined geography and politics, like the Kiever Revolutionary Branch No. 25 of the Arbeter Ring (founded in 1906) or the First Proskurover Young Men’s Progressive Association (founded in 1904). Klezmorim became members of these organizations along with workers in other trades and also developed longstanding relationships by performing at their social events — like masked balls, dances, and strawberry socials — and official functions such as the annual election of new leaders. As a Bialystoker landsmanshaft might recommend “their” barber and “their” butcher to their members, many also cultivated ties with “their” musician when it came to official events and members’ weddings and simchas. A similar dynamic developed around trade unions, which likewise regularly hired union bands for their marches, dances, and anniversary banquets.

The next large wave of klezmer musicians arrived around 1905; some were fleeing conscription in the Russo-Japanese War or the violence and pogroms that followed the failed 1905 revolution. This wave of immigration was notably more secular and political and included many more individuals who had been initiated into Bundist or revolutionary politics.

Most of the klezmorim who made commercial 78 rpm recordings during the First World War arrived in this wave, like the violinist Max Leibowitz (1884–1942) and the cornetist Alex Fiedel (1886–1957). Also among them was Abe Elenkrig (1880–1965), a cornetist and barber who arrived from Zolotonosha in 1907 and made the first American klezmer recordings in 1913. (They can be streamed here.) His sister Eva Elenkrig (1889–1984) was also an interesting character who was active in socialist politics. She had played in the family band in Europe, but in New York, women musicians were essentially excluded from playing in klezmer orchestras. So she made her living as a seamstress. Recitals and artistic performances were considered more acceptable for women. In October 1909 she played the balalaika at a concert and literary evening held at New Harlem Hall for the 5th anniversary of the socialist paper Der Arbeiter.

By the 1910s, many of the elements of the 20th-century American music industry were still in their infancy. Commercially recorded music and silent film orchestras were very new and, in some cases, changed the public’s idea of entertainment. Copyright and music royalty laws were still being tested with lawsuits, and musicians' unions did their best to keep up with all these changes. In this era, Yiddish-speaking Jewish musicians became increasingly involved in many parts of the music industry, and the need for a separate union declined. Local 310 of the American Federation of Musicians, founded in 1902, had grown important enough by the early 1910s that it started accusing the Hebrew Trades union of being a “dual union” that should be investigated. Probably as a business decision, many klezmer musicians opted to join Local 310, such as the clarinetist Naftule Brandwein (1884–1963), who became a member in 1913. By the time Local 310 was reorganized as Local 802 in 1921, the remaining members of the Jewish musicians’ union joined it and converted their former union into a mutual aid and burial society (the Progressive Musical Benevolent Society).

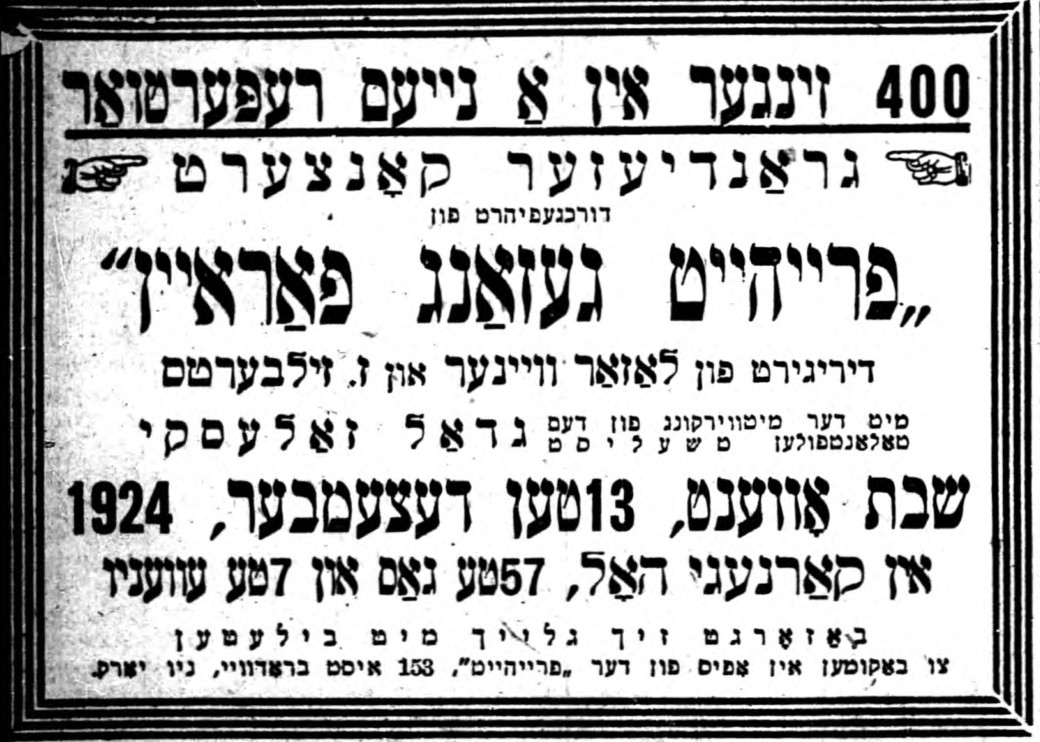

Another Yiddish socialist musical trend took root in this era: the secular Yiddish chorus and its instrumental counterpart, the mandolin orchestra. The first secular Jewish choir was created in Łódź in 1899 and the first American ones in Paterson, New Jersey and Chicago in 1914. The idea soon spread to other cities, although in New York the most famous of these singing groups, the communist-affiliated Freiheit Gezang Farein, wasn’t founded until 1923. These choirs also had parallels in many non-Jewish immigrant cultures in America, including in various Scandinavian and Central European ethnic groups. Their relative simplicity and accessibility in comparison to klezmer allowed a number of Jewish political and cultural organizations to found and operate them for their members. Musically speaking, they had little to do with klezmer, and klezmer musicians, for their part, seem to have had very little involvement with them, as most of the well-known choir leaders came from the art, music or classical world.

Left: Yiddish-language advertisement for the New York-based Freiheit Gezang Farein choir's concert, appearing on Dec 9, 1924, in Der Tog. Conductors given as Lazar Weiner and Zavel Zilberts. Right: Group photo of the Freiheit Gezang Farein chorus (a Yiddish-language communist choir), New York City, 1923. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The outbreak of the First World War in Europe, combined with new restrictive immigration policies, heightened the difficulty of immigration, and therefore few klezmorim arrived in New York in the second half of the 1910s. In some ways being cut off from Europe did give opportunities to klezmorim who were already in New York. For example, record labels could no longer travel abroad to record “ethnic” artists and began to seek out local talent to record for various immigrant markets. Klezmer musicians filled this niche and often recorded different repertoires for Romanian, Jewish, Ukrainian and Russian markets.

In 1916 Eva Elenkrig, who had played at the Der Arbeter anniversary back in 1909, reappeared in the pages of the Weekly People, the paper of Daniel DeLeon’s Socialist Labor Party. DeLeon had died in 1914, and Eva was hosting fundraising meetings with the Jewish Press Committee at her place on East 119th Street in an attempt to launch a new Yiddish-language newspaper, as well as the translation of DeLeon’s works into Yiddish. The violinist Jacob Gegna played one of the benefit concerts for this committee on Christmas Eve 1916.

Another political klezmer performance from this era was a Full Dress and Civic Ball held on September 29, 1917, by the Britshaner Bessarabier Young Men’s and Young Ladies’ Benevolent Association. Taking place at Beethoven Hall on East 5th Street, it featured the Fiedel Brothers Union Double Brass Band, with proceeds going to the People’s Council of American for Democracy and the Terms of Peace, an anti-war movement which was opposed to Woodrow Wilson’s decision to enter the war in 1917. Meetings and rallies of this group were regularly attacked by hostile mobs, disrupted by the police, and targeted by politicians.

In the years after the war ended in 1918, many musicians seem to have continued with their prewar professional and political orientations, whereas others became members of the Communist Party and increasingly oriented towards the Soviet Union. A few started to incorporate Zionist themes into their compositions, though support for Zionism was still a minority position among New York Jews at the time. The booming economy of the 1920s meant many of these musicians moved beyond the Lower East Side and into other parts of New York, and some, later, to Hollywood, where the immigrant labor radicalism they had been embedded in was no longer relevant.

From the early days of the 1880s to the First World War, klezmorim were present at every twist and turn of immigrant Jewish radicalism and labor organizing, from strikes, which would feature huge brass bands playing celebratory music, to union elections, when a march would be played as candidates approached the podium. This is not because they were uniquely radical; in fact, their own views are often poorly documented and unknowable to us today. But the presence of klezmer musicians at nearly every notable Jewish event seems to have been very important to people in that era. For many of these musicians, their integration into these labor spaces and movements also led to further radicalism and party involvement, driving them to continue supporting labor and communal solidarity throughout their lives.