The Bund and Colonialism - The Perspective of Wiktor Alter

Writings by Bundist leader Wiktor Alter and a 1931 resolution endorsed by the Bund shed light on Bundist political thought on imperialism and colonialism.

As part of the renewed interest in the Jewish Labor Bund, much attention has been given towards the examination of its attitudes as they might relate to the contemporary context of Israel-Palestine. Much of the Bund's pre-1939 criticism of Zionist movements was directed towards their damaging effect on Jewish culture and communities in Diaspora, as well as in what would become later the State of Israel. Alongside this, however, there is also an undeniable historical record of Bundist writers arguing for the rights of the Arab-Palestinian population. This has led to further curiosity regarding the Bund's general attitude towards the rights of peoples under foreign or colonial rule, particularly beyond the European context. Following the recent blatant imperialist actions of the Trump regime in Venezuela and similar threatening behaviour towards other countries, the issue has become even more immediate.

Of the limited available materials on the subject, the easiest to find is a resolution adopted in 1955 by the 3rd World Conference of the Bund, which I transcribed and introduced last year in Der Spekter. (Conveniently, it was originally published in English). As the Bund chose to unequivocally align itself with the Western powers in the Cold War, it perceived the communist movements in Korea, Vietnam or China in the same way as it perceived communist governments in Eastern Europe: unpopular and based on foreign occupation. This Europe-centred lens did not allow room for the fact that the communists in these countries may have been leaders of anti-colonial popular revolts supported by the majority of the population (particularly in Vietnam) or that anti-communist forces may have been more brutal, more dictatorial, and more foreign-backed than the communist forces were — or at the very least, equally so.

You can read more of my contextualisation of the Bund's stance in my introduction to that piece. Given the personal experience of many Bundists present in Montreal at the time that resolution was passed, I would caution Khaveyrim from making too harsh a judgement on this resolution, and also take into account the explicit condemnation of pro-Western dictators and the call for "the liquidation of all remnants of capitalist colonialism […] to assure freedom, prosperity and social justice for the many hundred millions of people in the undeveloped countries of the world." If there is any particular shame that was brought to the name of the Bund in this regard in this period, then the best example would be the French Bund's refusal to condemn the French government's war on Algeria, which is covered in detail by David Slucki in his book on the Bund after 1945.

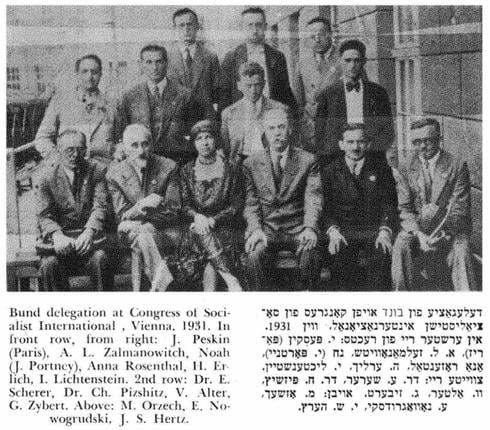

I wish to bring to light a lesser known document — one written by the Bund in an earlier and stronger period of its existence. Exactly one hundred years ago, Wiktor Alter, one of the leading writers and activists of the interwar Bund in Poland, later executed on Stalin's orders, published a short book titled "A Fighting Socialism” (“Socjalizm Walczący” in Polish, “Der Sotsyalizm in Kamf” in Yiddish). Alongside many of his other works, such as “When Socialists Come to Power” (1934), “Unity and the Plan” (1935), and “Man in Society” (1938), it has been scanned in recent years by the Polish National Library, uploaded online, and left in the public domain. All of these works are extremely enlightening on the political thought of the Bund and deserve to be fully republished in Polish and translated into English. Leaving that aside for now, “A Fighting Socialism” contains within it a chapter on various aspects of the “the National Question” including a small subsection on “the Colonial Question.” I have translated it in full and it can be found below. Additionally, I also translated a small excerpt from a resolution sponsored by the Bund at the 1931 Congress of the Socialist International (full credit to Monika Nestorowicz for finding it in the Polish State Archives). Its perspective on imperialism and colonialism resonates strongly with Alter’s writings; unsurprisingly, he was a Bund delegate at the Congress.

Alter also published an account of his travels in Mandatory Palestine in 1925, titled “Der Emes Vegn Palestine” (“The Truth About Palestine”). Since Molly Crabapple has looked at this work in detail for her forthcoming book, (I will write more about Palestine in my Bundism Today series), I will focus on Alter's general attitude to colonialism beyond the Palestinian context.

In the limited space he dedicates to the subject in “A Fighting Socialism,” Alter's criticism of imperialism and colonialism is brutal and clear-cut. He is particularly harsh towards what we would today distinguish as settler colonialism. The fact that his prediction on the tragic complete elimination of Native Americans and other indigenous peoples did not fully pan out leaves some interesting room for discussion on how the Bundist framework should approach modern discourse on “reparations” or “land back.” Alter also sees right through the facade of supposed liberalisation of colonial rule through mandates, protectorates, and preferential trading rights — something still highly relevant today in the endurance of neocolonialism — and the absurdity of Europeans embarking on “civilising missions” through barbarous oppression. Like many other socialists of his time, he also saw imperialism as a result of capitalist desire for growth and a significant contributing factor to the First World War.

Most important, however, is Alter's insistence that even the sincerest form of outrage is not enough. This stance, reminiscent of Henryk Ehrlich's criticism of Lenin, indicates the Bund's clear antipathy towards demagoguery and adventurism. As part of trying to re-shape reality, a clear policy-based political vision was needed. Doing that, in turn, required recognising important nuances. On the one hand, Alter is clear about his unambiguous support for liberation from colonial rule being the duty of every socialist, which is reflective of the Bund’s general stance on the matters.

This sentiment was echoed by future generations of Bundists, Slucki writes, including Dina Ryba, a Bundist based in France in the 1950s, who heavily criticised the French Bund's official stance on Algerian independence, arguing that it stood “against the tradition and spirit of the Bund, which has throughout its history always stood straight and openly on the side of oppressed peoples in their struggle for liberation” (emphasis in original).

Alter does make it clear, however, that this stance should not translate into blind support for any individual or political movement claiming the mantle of anti-imperialism or anti-colonialism. Instead, European socialists should support socialist movements in colonial countries on a partnership basis, just as Polish socialists should support socialists in other European countries without calling into question the political independence of any country.

To further illustrate his nuance, Alter also argues that the liberation of colonised peoples will practically and directly benefit the struggle of the European working class. Supremacist systems do not benefit the working classes of the ethnic, religious, racial etc. groups at the top of the supremacist pyramid. From an intersectional perspective, we can understand, for example, that the oppression faced by white workers makes their oppression systematically weaker than that of workers identified as lower in the racial hierarchy, but that they will still benefit from the overthrow of white supremacy.

There is one big elephant in the room regarding the piece: some of the terms used by Alter to describe certain people of colour. While they can be contextualised given the time and space they were used in, that should not be equivalent to dismissing any interrogation of their use. The Polish terms "czerwonoskóry" and "murzyńskiego," referring respectively to Native Americans and Subsaharan Africans, are considered outdated today, at least in contemporary and developing progressive discourse in Polish society. I decided to keep the translation as faithful as possible, believing that "negro" is a more faithful translation of the original than "black," despite some disapproval this may create from certain Polish linguists.

More grating still is the fact that while Alter notes that European claims to "civilise" colonial peoples should be taken with a massive grain of salt, he also speaks of countries such as Morocco or Syria as being of a "lower cultural level." While this contradiction could be understood as originating within a Marxist interpretation of pre-capitalist feudal societies, the lack of an outright anti-racist clarification is an unfortunate oversight at best and evidence of racial bias at worst. A similar criticism of ambiguity can be made of Alter’s statement that the future of all European colonies is in question, “except those inhabited by the black race” (emphasis added to highlight the outdated language).

More damningly, perhaps, is that even though the Bundist youth education stressed the importance of racial equality in its materials, there is at least one notable incident where such high standards were not kept in the slightest. A 1931 pamphlet of the Tsukunft (youth organisation of the Bund) titled “Komunizm Iz Nisht Der Veg” (“Communism is Not the Way”) claimed that communists in one Polish town had been so brutal towards the Bund that their methods can only be compared to those of Chinese communists or those organising “within other backward peoples.” Notwithstanding the brutal violence with which certain Communists acted towards the Bund (such as the attack on the Medem Sanatorium which took place the same year) the use of such language should have been criticised at the time as racist and inconsistent with the ideals of the Bund.

Overall, I believe that the piece (and the accompanying 1931 Resolution) are relevant and eye-opening perspectives into the Bund's approach on colonialism and imperialism. Alongside other works, such as the educational materials of the Medem Sanatorium, it shows the longstanding roots of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist thought in the Bund. Where it falls short, it should be further elaborated and discussed by our generation of Bundist writers and tuers.

There is plenty more that could be written regarding how Alter's writings tie into the attitudes of his socialist contemporaries towards colonialism, particularly socialists of colour; as well as the specific aspects of racial identity and colonialism in Interwar Poland. I would personally recommend the highly readable (if you read Polish, that is) "Bzik Kolonialny" by Grzegorz Łyś for some more insight into the latter. For now, though, I leave you with the words of Wiktor Alter.

Zach Mojsze

Wiktor Alter - Socjalizm Walczący (Drukarnia I.Hendlera, Warszawa, 1926) - s. 90-94

Wiktor Alter - “A Fighting Socialism” (1926) - pp. 90-94.

Colonial Policy

Finally, the matter of colonial policy. An extremely intricate and complicated matter.

Here, too, it is easiest to formulate a negative, critical position. The exploitation practised by larger and smaller European countries towards the populations of the countries of Asia and Africa is a glaring injustice. The unprecedented trampling of human dignity and life in all sorts of colonies is a disgrace to humanity. The ‘civilising’ actions of Europeans in the virgin forests of Africa are imbued with a savage barbarism.

The sincerest form of outrage, however, is not a political response, and we are primarily concerned with the matter of politics.

For many years, colonial policy boiled down to a policy of colonisation. In places where the climate and soil were not very different from European conditions, the white race systematically, deliberately, and with unprecedented cruelty exterminated the indigenous population. Today, the final act of this tragedy is being played out.

There are still remnants of the former Mongolian population in north of Siberia, of redskins in America, and of negro tribes in Australia. But these are already the “last of the Mohicans,” whom European “civilisation” (vodka and infectious diseases) will soon wipe off the face of the earth. The mass murder is being carried out amid the general silence of the graveyard, without a single loud protest.

When lands for colonisation areas became exhausted, colonial policy took a different turn. Attention was turned to countries where Europeans could not live a la longue, or where there are no prospects of exterminating the natives. The first group includes most African countries, while the second includes Egypt, Morocco, India, China and others. Initially, the aim was almost exclusively to collect tribute – through a legal route (through taxes) or through outright robbery. After that, new markets for domestic production were sought there. Recently, attempts have been made to invest there forms of capital which yielded significantly higher returns than in the metropolis (mainly due to low labour costs). The most valuable colonies became ground for transplanting capitalism and all its accompanying phenomena (the creation of a proletariat, the stimulation of the population to active political life, etc.).

The possession of colonies became a measure of the power and wealth of European countries. England was in the forefront, its prosperity being largely based on the income squeezed out of its colonies.

Other countries followed its example. All efforts were directed towards obtaining new opportunities for expansion, new colonies. Against this background, inevitable friction arose between individual countries. Against this background, the last world war broke out.

After the war, colonial policies underwent some changes, becoming more “Europeanised.” Instead of brutally and cynically imposing their power, the colonial powers invented “mandates,” “spheres of influence,” a kind of “protectorate” (Egypt), appropriate “trade agreements” (China). The goal remained the same: to reap the greatest possible profits for the “civilised” rulers of Europe, to find an outlet for their excess productive forces, both goods and capital and people.

But the situation became more complicated due to the growing desire of many colonial peoples to put an end to this state of affairs. Japan has proven that the “natural” supremacy of Europe is a fiction, that it is enough to have the will and strength to free oneself from uninvited guardians. Turkey recently achieved liberation with one powerful effort. China, India, [and] Egypt openly proclaim their desire to throw off the shackles of foreign oppression. Even countries with a lower level of culture, such as Morocco and Syria, are rebelling against the invader and demanding freedom with weapons in their hands.

One may have a thousand reservations as to the worth of the governments of Abd-El-Krim or Zhang Zuolin. But the “Europeans” Horthy and Mussolini are not worth much more than them. The question of the attitude of the working class or socialist states towards bad governments in other countries is a very serious one, but not necessarily relevant to colonial issues. As long as the independence of present-day reactionary Hungary is not called into question, platitudes about Europe's “civilising” mission towards the peoples of Asia and Africa will remain a hypocritical slogan, concealing the most ordinary capitalist greed for others’ property.

Thus any socialist who swallows this bourgeois rhetoric would be making an unforgivable mistake. All the more so because his efforts to save Europe's current possessions on other continents would be doomed to failure from the outset. The era of European domination over its richest colonies is coming to an end. It may be sooner or later, but the outcome is a foregone conclusion.

"It is the duty of socialists to help colonial peoples in their struggle for freedom. This lies in the direct interest of the working class. For the bankruptcy of the current colonial policy will further expose the rottenness of the current system."

And let no one be misled by talk that it is not the twilight of colonial policy that is approaching, but that Soviet Russia wants to grab juicy bits of Asia for itself. The subjective appetites of the Russian government are irrelevant in this case. What matters is the result. In this respect, the example of Turkey is convincing. After its victory, achieved with the help of Soviet Russia, it hanged the entire central committee of its Communist Party. This did not prevent it from re-establishing an alliance with the Soviet government over [the question of] Mosul.

All European colonies are in question, except those inhabited by the black race. We will not touch here upon the interesting negro question. Let us only note that these colonies are among the poorest and, in terms of climate, the most harmful to the health of Europeans.

It is the duty of socialists to help colonial peoples in their struggle for freedom. This lies in the direct interest of the working class. For the bankruptcy of the current colonial policy will further expose the rottenness of the current system. When the stream of gold flowing from their colonies to the metropolis dries up, when Europe has to live off its own labour, when capitalism has to further restrict the use of society's productive forces, the question of social reconstruction, the question of the end of capitalism, will arise with redoubled force.

And when socialist states are established, they will be faced with a question in all its entirety: What to do and how to act to accelerate the victory of socialism in countries still under the yoke of capitalism? Both in Europe and America — in Asia and Africa.

That is no longer a matter of colonial policy, but of the general policy of victorious socialism.

Resolution of the Left at the Vienna Congress of the Socialist International (1931)Submitted by the Jewish Labor Bund (Poland) and the Independent Labor Party (UK)Addressing Agenda Item 1:

THE STRUGGLE FOR DISARMAMENT AND AGAINST THE DANGER OF WAR. Part 4 [out of 5]

The Congress declares that imperialism maintains a constant threat to peace. The Congress recognises the right of every nation to independence, considering the realisation of this right to be the only basis of a true internationalism. Saluting all peoples standing in the fight against imperialism, the Congress expresses its satisfaction to the people of India for their heroic efforts to achieve political freedom, recognising their demands for self-government, including the right to independence. The Congress welcomes in particular the growing strength of the proletarian forces within the Indian national movement and rejoices at the resolution passed at the Indian National Congress in Karachi, demanding a minimum wage for the whole country and the socialisation of key branches of industry and transport.

The Congress expresses its sympathy and readiness to help the peoples of Egypt, the Middle East, Palestine, the Dutch East Indies, Africa, China and other parts of the world in their struggle for political and social liberation, calling on the socialist parties of the imperialist countries to support these peoples by all means.

Aware of the growing danger of economic imperialism to peoples who have hitherto been nominally politically free, the Congress stands in solidarity with their efforts to free themselves from the shackles of foreign capitalism. The Congress sends greetings to the peoples of South and Central America, who are fighting for the right to exploit the natural resources of their countries without the interference of foreign capitalists.

Source:

AAN, Ogólno Żydowski Związek Robotniczy "Bund" w Polsce 1900 - 1948

1214/2/30/II-7

s. 80