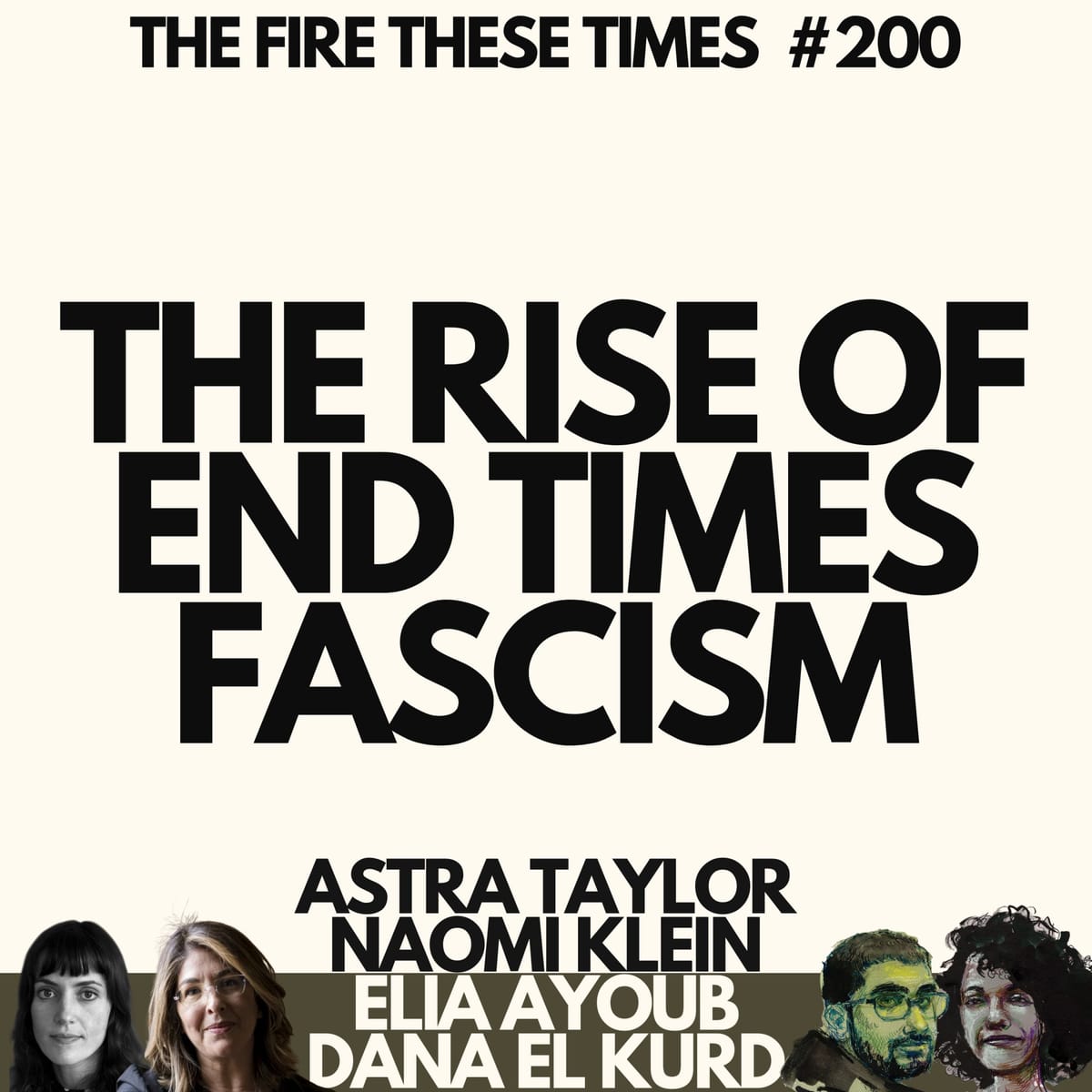

The Rise of End Times Fascism w/ Naomi Klein & Astra Taylor

"These people are traitors — they are treasonous to this world and the wonders of this world. They’re not traitors to nation; they’re traitors to creation."

Der Spekter thanks Elia Ayoub and the Anditode Zine for allowing us to republish the transcript of Elia and Dana's incredible interview with Astra Taylor and Naomi Klein. We encourage you to find The Fire These Times podcast at your favorite podcast app, listen, and subscribe.

Transcript via Antidote Zine:

This is an opportunity for us, because they’re scared of how untenable this is. I’m a little bit obsessed about that, because it’s also beautiful: we have to help people fall in love with the world again.

Dana El Kurd: Hello everyone, and welcome to The Fire These Times. My name is Dana El Kurd and I’m co-hosting this episode with Elia Ayoub. Today we are joined by Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor to discuss their recent essay in the Guardian, “The Rise of End Times Fascism.”

Naomi Klein is an award-winning, best-selling author of many books as well as professor of climate justice at the University of British Columbia. Her latest book, Doppelganger, was released in September 2023 and won many awards, including the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction. We have an episode where we discuss Doppelganger at length with her.

Astra Taylor is also an accomplished author, has written many books, including Democracy May Not Exist, but We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone, The Age of Insecurity, and many more. She is a documentary filmmaker as well as a writer, an activist, and co-founder of the Debt Collective.

They join us today to discuss their essay and the implications we can derive from it. They talk about what the billionaire class is up to, the dangers of AI, and all the challenges we’re going to see in the near future (and that we’re already seeing) — our conversation looks further than that: how are we equipped to fight this? What is the power of our narrative?

What binds together this weird Frankenstein coalition of Bannonite hypernationalist xenophobes and the billionaire space colonizers is basically an acceptance that we are at the end of whatever this project is, and we may as well get ready with our various bunkers

Thank you both for joining us and for making time.

I enjoyed — or, was mostly horrified by — the essay in the Guardian, but the themes y’all brought up are important to talk about. The first basic, broad but simple question is: the Trump administration and its billionaire backers are attempting to break everything; it’s this critical juncture where change can happen, where ideas that emerge will shape the trajectory of that change, so do we think the left (broadly defined) is prepared with the right ideas to present in this moment?

Naomi Klein: The left is more prepared, from a policy perspective, than it has been in earlier moments in the neoliberal economic project when these tactics of exploiting a state of chaos to push through a radical corporate agenda, which I call the “shock doctrine” — there have been moments when the left has been caught much more flat-footed in terms of having its own ideas. In the past decade, a fair amount of progress has been made in taking ideas and policy more seriously that are not just defensive, not just saying, Stop the cuts!

I grew up in the “stop the cuts” era, as opposed to a Green New Deal, abolition, the work Astra does with the Debt Collective, putting our own radical visions on the table. We are readier with policy ideas and grand political ideas — but that’s not the same as being ready, from an organizational standpoint, to advance those ideas, or even ready from a narrative/affective standpoint.

The apocalyptism on the right is really marshalling the power of the most potent myths in our culture — not just to advance policy, but really to get fire-and-brimstone on all of this and tap into that narrative power. We are still weak on that, on the left, and that’s part of what Astra and I get to in the latter part of the piece: if what binds together this weird Frankenstein coalition of Bannonite hypernationalist xenophobes and the billionaire space colonizers is basically an acceptance that we are at the end of whatever this project is, and we may as well get ready with our various bunkers, that should push us to think about what our grand narrative is about. I’ve found the Bundist idea of “hereness” a really powerful one. We quote friend of the pod Molly [Crabapple] in the piece.

So there’s different parts of it: there’s the policy piece, where I’d say yes. But a point Richard Seymour has made, talking about disaster nationalism, is that we’re not going to fight the end-times fascist fire with heat pumps for all! Heat pumps are good, but that’s not going to capture people’s imagination.

Astra Taylor: I love what Naomi just said. Policy is important, but there has to be a prophetic element to it as well; we need that prophetic sense that we have a cause that’s bigger than ourselves. That’s really important.

Just to dig into the power problem: we don’t have the power. We’re not organized at the scale we need to combat the right, for lots of reasons. And we’re in a period of actively being divided and conquered, so that makes this terrain difficult. Some of those fissures — Gaza was a huge issue breaking liberals and leftists; also the Trump administration further criminalizing dissent (not that they invented that as a tactic). In that sense we’re on pretty challenging terrain.

Our policy vision was a huge step; when I was twenty, Naomi was the left. The left was so weak.

NK: That’s such a sad statement.

You don’t get beacons of liberalism like international human rights frameworks and the basic welfare state without an underlying framework of socialism, economic equality, and those kinds of commitments

AT: That’s why you were so important and still are. Now the left has ideas; we know we’re kind of popular. But that’s being actively erased by the “abundance” agenda, by these liberal ideas that are almost acting like the Green New Deal never happened, that the idea of free college for all and the end of student debt wasn’t on the table, that there hasn’t been a movement demanding healthcare for all for years. That erasure is something that’s working against us, and we have to be really vigilant against it and push back.

Green New Deal advocacy posters. Courtesy of Poster House

DK: It’s good you mentioned Gaza; that was going to be my follow-up. In the wake of the genocide that we’ve seen and that’s continued, many people in the progressive or leftist space who may have held out hope in some aspect of our institutions and some aspect of our international system are coming down on the side of, “actually the entire edifice is rotten, so let’s break everything and start anew.”

There is an element of the left that may in fact not be sufficiently outraged when Trump and his billionaire backers break these institutions, because some of these institutions are garbage. One example is USAID (I’m not saying everything that institution did was garbage). What do you think the leftist response should be to this breaking of what was clearly a biased and deeply problematic, imperfect global system?

AT: I have an emotional response to your question, which is Yeah, I get it. I get the anger that people feel at broken institutions. One of my previous books was called Democracy May Not Exist, but We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone. We can make progress — it’s never perfect, it’s hard-won — but things can go into reverse. International human rights is a nice idea; we should try it!

One point, according to my leftist philosophy, is that you don’t get beacons of liberalism like international human rights frameworks and the basic welfare state without an underlying framework of socialism, economic equality, and those kinds of commitments. Cheering the breaking of broken things is a risky place to be. I’ll be specific about student debt cancellation and higher education: I’ve been fighting for student debt abolition for the last ten years, and right now the Trump administration is taking the student lending system and making it even more punitive, disastrous, and punishing for working-class people, taking that apparatus and not abolishing it but abolishing the helpful parts and keeping the parts that extract wealth from working- and middle-class communities.

Now we’re in a tension where we have to say, “Stop! Protect this thing we wanted to eliminate before! so we can have a better chance building a movement that fights for our big vision of democratic higher education.” That’s just one of those tensions we have to inhabit as organizers who want to have a real impact and improve people’s lives. It can feel shitty to have to defend something that is imperfect — and imperfect doesn’t even describe it; sometimes aspects of these institutional structures are actively harmful.

But it’s one of those laws of the universe that it’s easier to destroy than to build. We’re working against that. It’s tough, and right now I’m really feeling that in my own arena of work. We’re having to do this dual movement of trying to protect and defend while also saying, This was never adequate.

NK: I don’t think there’s one answer. It really depends on the thing that’s being broken. USAID is not a monolith — there are some good things that happened in USAID. There are some things that DOGE and Trump are destroying that are unequivocally going to make people’s lives far more miserable and shorter — just spreading death.

This week, RFK Jr. announced that pregnant women are no longer going to be recommended to get the COVID vaccine; that is going to kill babies. It’s incredibly ironic because all these folks are so “pro-life,” but a basic understanding of what happens to an immune system that is pregnant — this combination of recommending that kids don’t get the vaccine and that pregnant mothers don’t get the vaccine is just going to mean death. That’s just one example. That’s a straightforward thing.

I feel very fortunate not to live in the United States. I live in Canada; my parents left during the Vietnam War, and I’m grateful to them. One of the things I’m focused on is what our responsibilities are in places that are not living under Trump, in terms of making good on some of the bullshit liberalism that our governments are still spouting. What does that mean in terms of how we can do a better job of exploiting this anti-Trump discourse that we’re hearing? Right now Canada has a double central banker as its new prime minister, and he’s doing this “elbows up” fighting Trump, but he’s just going to do Trump-lite in Canada — that doesn’t mean we don’t have opportunities to make good on some of the anti-Trumpism that’s being unleashed.

That’s very true in the multilateral arena. US influence — whether it’s Democrats or Republicans — in multilateral spaces, almost without exception, is terrible. More things will be possible now that they’re gone. But we have to organize for it across borders. I’m thinking about it in terms of the climate space: the only thing the US government has done in the climate space has been water down agreements, make them meaningless, make them non-binding, put in shitty market mechanisms, and leave them. Now that our governments outside the US don’t have that excuse, what are we going to do with that?

DK: That divergence is an opening.

NK: Maybe, if we organize for it.

AT: The last thing we want to do is get stuck in something where we appear [to be] — or by default are — defending the status quo, which is broken. That is the trap liberals and the states fell into: We must save our democracy!

NK: Astra, how did you feel when Trump said he wanted to take the money from Harvard and give it to trade schools?

AT: The reality is — when I said they’re overhauling the student lending system, they are creating a field day for for-profit, predatory trade schools. These aren’t even schools! They are companies that purport to offer skills and are sometimes private-equity-backed Wall Street firms. So it’s the right words, but when you look under the hood, it’s just the worst oligarchic, destructive version of it.

NK: Is it an opportunity to be like, Yeah, community colleges should be one hundred percent free? I’m thinking out loud. Sometimes when people lie, it’s an opportunity to hold them to it.

DK: You can push them.

AT: One hundred percent. And a lot of it contains truth, because he’s right that there’s a vast injustice in the endowment possessed by Harvard and in the resources going to these schools. We have to build the power to call the bluff and put something else on the table. It’s a lot of work to do that, but it is our obligation to turn these crises into an opportunity. They’re not just opportunities — we have to make them into that. That’s the moral imperative of this moment.

DK: Especially in an environment where these “opportunities” are apparently never-ending.

Elia J. Ayoub: The example that comes to mind for me is: you ask most Palestinian refugees, and they have more than enough to complain about any UN agency, especially UNRWA — but you take UNRWA away, and things are so much worse. It’s not because UNRWA was this amazing thing; it’s just that there are no alternatives. That is why the Israelis have used attacks on UNRWA as part of this genocide; otherwise they wouldn’t have bothered.

NK: Coming back to thinking about what the betrayals of Palestinians have contributed to the weakness of any kind of coalition that could respond to these accumulations of crisis: I really think we have to spend time on it. We have to think about what repair would mean. Even just using words like “apocalyptism” and “end times” — the end times and the apocalypse is here; it’s just unevenly distributed, like all aspects of the future.

When you have a lot of American liberals going, We’re about to have fascism! We’re about to have an apocalypse! There’s a whole generation going, “Where have you been?” And if we don’t try to bridge those two worlds and understandings of where we are and temporalities of where we are, we’re going to stay static.

EA: The framework of “It could happen here” is that there are places where the “it” has already happened. There is an entire conversation to be had, understanding and decentering ourselves when the “it” feels like it’s “happening here.” In Lebanon, 2020 felt like the apocalypse with the pandemic but also with the Port of Beirut explosion. It felt like, this is it. Now when I talk to friends in Lebanon, it feels like we’re talking about the post-apocalypse—we’re not talking about the apocalypse anymore; this is the day after.

This doesn’t mean that things can’t get worse, of course, but it’s allowing ourselves (or trying) to inhabit multiple political temporalities at the same time. It isn’t easy, but it needs to be done. The conversation I had with Maram Humaid, a journalist in Gaza, is an extreme example—but it’s also not. Right now, her day-to-day is what it is, and it is very difficult to imagine. She has to adapt to what is happening; she doesn’t have a choice; she has two kids, she has to think about them.

We recorded, my friend Israa’ and I, and we said good-bye to Maram, and then it was just me and Israa’ — we had to take an hour break to do the introduction because we were out of words. We didn’t know how to even express things, because the urgency in her voice — in my mind, I don’t have this urgency on a day-to-day basis, but I had to inhabit that urgency while talking to her in order to empathize and make sense of it all, as much as I could.

I worry eternally that we mistake mobilizing and people going into the streets for power; it’s a critical point...power takes infrastructure; it takes strategic focus, more than going out in the streets. When people come to the mass Zooms we do, when people go to meetings I attend, it’s like, I’ve been to the protests—what else are we doing to build power, to really change things?

DK: M. Gessen has a piece out today in the New York Times about how we normalize these crises. It seems like a disaster, but you can always metabolize it; you can always get past it. It’s a human impulse to try to adapt and continue living, but it doesn’t blunt the urgency of the moment, and it blunts the urgency of our ability to mobilize effectively.

That’s a good segue to what I’ve been thinking about related to mobilization, specifically in the United States post-(second-term)-Trump. We’ve talked about Harvard, but the Crowd Counting Consortium at Harvard has been collecting data on the level of mobilization across time and space; they have a whole research project on the pro-Palestine protests, which has been very interesting to follow over time. But their findings show that in the first few months of 2025, people mobilized in the United States more than in the entirety of 2017.

How do we absorb that information, given everything we’ve talked about? Both in terms of the urgency but also how people can normalize these crises? Are people starting to understand that these are “end times” and there’s a nihilistic vision here? Or is this mobilization being used ineffectively?

AT: That’s a big question, and something I’m living with every day as an organizer trying to figure out how we can do better as the left. I was heartened by that data that said more people were turning out and going into the streets; I’ve been part of the protests since the second Trump inauguration. But I worry eternally that we mistake mobilizing and people going into the streets for power; it’s a critical point.

This is a both/and; it’s not a dismissing of protest. Protests are social proof that there are other people who care; they can be enormous demonstrations of discontent. The presence of the protests of this administration changed the media narrative; there was a sense of “Well, he’s legitimate this time! He won the popular vote! He has a mandate!”

But power takes infrastructure; it takes strategic focus, more than going out in the streets. When people come to the mass Zooms we do, when people go to meetings I attend, it’s like, I’ve been to the protests—what else are we doing to build power, to really change things? To win the Green New Deal, to win free college, to win an economy that’s not controlled by the billionaires? That’s tricky.

We also need to grow the tent. Mobilizing tends to mobilize the people who are already on your side. On this note of temporalities, people are in different places in their political journey, and I have to remind myself of this because I’m human and I’m an introvert and I get annoyed with people all the damn time. But we’re trying to build power to change the political system, to change our societies, to change the world—that requires a faith that people can change too, that people aren’t set in stone.

In this moment, it’s so frustrating — we were telling you what Gaza meant, that this wasn’t just something “out there.” But we have to walk people through a political awareness to understand the connections more deeply. This is a really powerful moment to say, The movement for racial justice after the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor — what we were saying about structural racism hurting everybody? Look at this! They’re using DEI to gut environmental protections and the welfare state, to unleash corporate power!

White supremacy is apocalyptic for everybody, it turns out. I live in western North Carolina, where we had a big hurricane last year. I was just reading in the paper about all the AmeriCorps people who were just kicked out of work as “waste, fraud, and abuse” by DOGE, and what struck me was that these people, who are in their twenties and are cleaning people’s basements and cleaning out the forests so there will be less risk of forest fires in the future—they were working for three hundred bucks a week and a per diem of $6.10 to eat. In the United States.

This is the “waste,” but they’re being disposed of because of DEI and “wokism.” This is a moment where there’s an opportunity for political education. Do you see that this racism is not something that just affects other people who aren’t your community? It’s in the hills of western North Carolina; it’s across the country.

DK: I saw that very normie, liberal, white professors are now talking about abolishing ICE. That felt heartening, I’ll say.

This doom-and-gloom, this hopelessness (which is not the same as pessimism)—I have found it exhausting and self-defeating. And this might sound a bit mean, but it’s sometimes a bit of a cop-out. It’s a way of avoiding the fact that this is very messy and requires work.

NK: The thing that gets me down is that I’m not sure we are engaging in the kind of introspection a lot of us were hoping was going to happen after the election. Astra and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and Chenjerai Kumanyika and I have these periodic mega-Zooms with Haymarket Books, and we had one right after the election and one a few weeks later — and it was definitely feeling like an opening. Part of what happened here was that we were irrelevant in this election — whatever we were doing as the left was easy enough to vilify, was not connecting with people, was experienced as censorious and scolding and exclusive and elitist enough that it was possible to turn away more working-class people, including a lot of young people and people of color who had not voted for Trump before.

There was definitely a feeling of, We have to look in the mirror, and we have to do better. Keeanga used this word — We need a “welcoming” left. That word “welcoming” is really important. It’s not a dogmatic word. But a natural part of feeling under siege is your horizons shrink, and then it once again becomes, How can I make the most maximalist demand of the smallest group of people? I don’t know; a few things have happened that have made me wonder whether we are learning that lesson. And we really have to learn that lesson.

Part of what we’re doing with the “end times fascism” framing is we’re connecting the dots between the Christian Zionists who believe in the literal end times in Palestine — and that’s part of how they not just rationalize but welcome the genocide — and part of how that connects with the attacks on trans bodies is all about a hatred of the corporeal, but then that rhymes with the fantasies of AI and uploading your intelligence into the AI singularity. It’s all about abandoning this place.

Part of what we are trying to think about is: is there a meta-story that could galvanize us? Excite us? Have that prophetic vision about really committing to the animate world?

I really do believe that what is happening with AI is something we all have to pay a lot more attention to, because this is something we can work with and peel away a lot of people who we lost. I’ve never seen anything like the hypocrisy of the populist right around the world claiming they’re going to fight for the working class and then immediately turning around and backing this technology that is going to do away with jobs (and already is doing away with jobs) on an unfathomable scale. It’s an absolutely vampiric technology, in the sense that it is draining the very lifeblood of the animate world—water, energy, the habitability of communities—in order to build these disgusting data centers so that they can…what?

No one is asking for this; it is all being foisted on us. Every search we now do — you don’t have to ask for AI; they foist it on us, and they burn the energy, and they suck the water to do it. I think this could be a kind of reset for the left.

AT: Not a “Great Reset”!

NK: I walked right into the right-wing conspiracy! You have to be internationalist to know what we’re laughing about, but the right believes we want a “great reset.”

DK: Our audience will get it.

AT: It’s amazing the right has built this coalition where there’s “You will not replace us” ethno-nationalists and “You will be replaced by AI” techno-enthusiasts — and you will love it!

This is your terrain, Naomi, but the reason Bannon goes on and on about AI is because this is not something that speaks to people on a gut level. This is not what they want for their kids.

NK: Bannon is deeply full of shit. He knows he needs to say that he’s against this, because his base is so against it. But he’s in bed with all these tech companies; he was in bed with the Mercers in 2016, who were early adopters of this, foisters of this. He’s saying just enough so that his base doesn’t rebel against him.

This is why I’m saying it’s an opportunity for us: because they’re scared; they’re really scared of how untenable this is. I’m a little bit obsessed about that, because I think it’s also beautiful. We have to help people fall in love with the world again.

AT: Just to reiterate: the left sometimes has the tendency to be like, It’s about being righteous and right. And I think what Naomi is saying is there’s a task of re-enchantment that’s as important as having the arguments or the right position on something.

There’s so much to wonder at! Research on the internet shows that what gets people to click is either outrage or awe. We need to have both in our mix as we’re trying to appeal to people’s sensibilities. They’ve been destroying this awe-inspiring world.

DK: For them and for their children.

NK: For what? For AI slop. This is the thing. Think about the amount of energy that this is requiring, and also the attacks on democracy that are happening. They bundled into this mega-bill that states and municipalities are literally not allowed to regulate AI. It’s wild.

AT: For ten years. They’ve preempted any regulation (ed. note: the final bill removed the provision).

NK: So they can use as much water and as much energy as they want. They’re building this in a lot of red states, very red areas. The opportunities for coalition are really broad. You can spin it however you want, but if people are turning on their taps and they have no water pressure because a massive data center down the road is sucking all their resources, it doesn’t actually matter what Steve Bannon says.

The entire Zionist narrative is a narrative of exceptionalism: that the Holocaust was entirely exceptional from other genocides, and that therefore rationalizes an exception from the postwar international humanitarian legal consensus.

EA: I find myself a bit at odds at times, because I find a lot of this weirdly hopeful. I make the distinction between “hopeful” and “optimistic”—I’m not optimistic, but I try to be hopeful. There’s a lot of contradictions in what they’re trying to do; we’ve listed a lot of them here. One of the examples you make is Musk being obsessed with colonizing Mars and clearly not having any love for the planet that he is living on, that we are sharing with him. Here, I’ll just quote a bit:

“Our task is to build a wide and deep movement, as spiritual as it is political, strong enough to stop these unhinged traitors. A movement rooted in a steadfast commitment to one another across our many differences and divides and to this miraculous singular planet.”

I’ve been going back to this from time to time, even in conversations that aren’t necessarily about that: we have a lot of tools at our disposal—and I don’t want to downplay the actual damage being done every day, but we also tend to downplay or underestimate what we can do. Also, as importantly, when we do succeed in achieving something, there is a tendency to immediately move on, not actually taking stock of the fact that we have achieved something and that is important.

There are a lot of things that even the right has basically adopted from the left, and that is not a victory, but it is worth reflecting on when we are successful in shaping the culture, in shaping how people think about what is possible—those are lessons in and of themselves; we are not reinventing the wheel. I’m not expressing this as well as I could, but this doom-and-gloom, this hopelessness (which is not the same as pessimism)—I have found it exhausting and self-defeating. And this might sound a bit mean, but it’s sometimes a bit of a cop-out. It’s a way of avoiding the fact that this is very messy and requires work.

On Gaza — people who give up on Gaza — it pisses me off. It’s not something that we should allow ourselves to feel. Feeling tired and exhausted, burned out, needing to take a break — all of that is normal and fine. But to accept (which is essentially what it is) the end goal of what the Israelis are declaring they want to do… I don’t know how people have accepted what they’re saying, that they want to ethnically cleanse ninety-five percent and put everyone in a concentration camp in the south.

How horrible is it? Of course we complain about it, and we call them genocidal Nazis and so on (and whatever, we can do that), but it doesn’t mean it’s inevitable that they manage to do that. It doesn’t mean there aren’t pressure points. This is more in-depth in other episodes that we do, but this comes to mind time and time again — of course Gaza is always on my mind now. That’s just an example I’m using, but it can be applied to so many other topics that we’re talking about.

Canceling debt could happen. We could actually manage to do that. Even with the worst people in power. There are certain mechanisms that we can use to apply pressure. I’m ranting a bit, but giving up is something I’ve gotten more angry about in recent weeks, as things have gotten worse in Gaza. People in Gaza do not have that luxury, that option, in the first place, so I don’t know why we should pretend like we do.

NK: I’d be interested in Dana’s take on this as well, because this is something we’ve talked about before, but we both don’t have the right to give up — nor do we have the right not to examine our own tactics and not try to come up with new tactics if our old tactics haven’t worked. Both of those are duties of the atrocities.

Part of the work of being in solidarity with Palestinians under genocide, or under occupation and apartheid, is the work of de-exceptionalization. The entire Zionist narrative is a narrative of exceptionalism: that the Holocaust was entirely exceptional from other genocides, and that therefore rationalizes an exception from the postwar international humanitarian legal consensus.

When we de-exceptionalize, whether we’re doing it with historical de-exceptionalism and tracing continuities from settler-colonialism to the Holocaust (which isn’t the same as saying it’s the same, but it is placing the Holocaust in history), part of what is fertile about understanding the apocalyptism of the narrative and the connections between different aspects of the right is that it is a re-frame. It is a way of understanding what is happening in Gaza within the context of a broader war: not just on the future, but on the Here.

There’s a difference between a war on the future and a war on the Here. Walter Benjamin warned that people are more motivated to avenge their ancestors and the losses and the martyrs than they are to fight for an amorphous future — but people are very motivated to protect this place, this Here, the hereness of this planet. Which also means avenging and “redeeming,” in Benjamin’s term, the defeats of our movement ancestors.

I just think it might be helpful, too. I want to stress this isn’t about “moving on from Palestine.” Somebody who really helped me understand that is the singer Anohni, who I had the opportunity to interview, and I asked her about what she saw as the connection between the attacks on the Earth, the anti-climate policies of the Trump agenda, and the anti-trans agenda. And her response was that they are both attacks on the body, and they are both part of the narrative of the Rapture. It’s all about trying to be free of the body, whether it’s the physical body or the world-as-body.

That was so helpful to me, to understand Zionism.

EA: I had written a piece on punishing the land. They’re harming Gaza as land as well, in addition to killing and harming human beings. That has been part of the project in the first place, this obsession with what is existing right now, what is Here — it’s not that we can just take it; no, we have to destroy it first. We have to rebuild anew.

I had a recent episode with Amos Goldberg, an Israeli historian of the Holocaust, and he’s one of the most vocal Israelis who have called this a genocide. The reason I’m bringing him up is he had a very interesting passage in a paper he wrote last year that took me aback a bit when I read it. In the field of comparative genocide studies — that’s what he does; it’s his academic field — he found that a number of the historians of the Holocaust who previously (before October 7, 2023) were saying the Holocaust is unique and cannot be compared to anything else were very happy to compare Hamas to the Nazis and say that Israel is fighting the new Nazis. They broke their own rule, effectively.

Whereas it’s people like him in this field who, from the beginning, had no problem saying, “This is not Auschwitz, but it is still genocide. This is not the Holocaust, but it is genocide. There are other ways in which it can be genocide.” We had a conversation on that, and it spoke to the urgency of the moment.

Dana and I have also had conversations, including on this podcast, about the problems that come when the Palestinian cause is exceptionalized and even fetishized. Dana and I are both Palestinian, and she also grew up in Jerusalem, and this is something that we found harmed the cause, even before the genocide, in making connections with (for example) the Syrian revolution or with Sudanese — and I’m just talking about the region here, let alone the broader world.

It has been more the problem of non-Palestinian spaces that are pro-Palestine than of Palestinians, although it is still a problem within our spaces as well.

DK: While I think you’re right, this is an issue that non-Palestinian spaces in solidarity with Palestine have, also in Palestinian spaces — there’s a disconnect between the diaspora and people in the region, but speaking from my positionality in the United States, for the sake of maintaining a “correct” tactic or line, a “pure” line on this issue, they’re almost willing to sacrifice Gazans or Palestinians to more genocide.

I think people don’t fully recognize that the Israeli state’s narrative is this ethno-nationalist, singular narrative of what this conflict means, both to them and for us, so de-exceptionalizing not only our understanding of what’s happening right now — not because we want to move on from Palestine but because Palestine is one part of the broader struggle against end times fascism — but also to de-exceptionalize the future we can imagine will mean expanding our narrative to include more richness of human existence that the ethno-nationalist, singular narrative wants to flatten.

Because of the genocide, and because of the fractured left to some degree, people have fallen back on more limiting narratives and exceptionalize the issue, fetishize the issue. I understand where it comes from; especially if you’re in the diaspora, you just feel disempowered. But there’s a medium- to long-term problem with that track that sets up the Palestinians — and a lot of people — for more violent outcomes.

Solidarity is about reaching across difference, finding commonalities without erasing differences, so we can find allies and build that future where nobody has to endure a genocide.

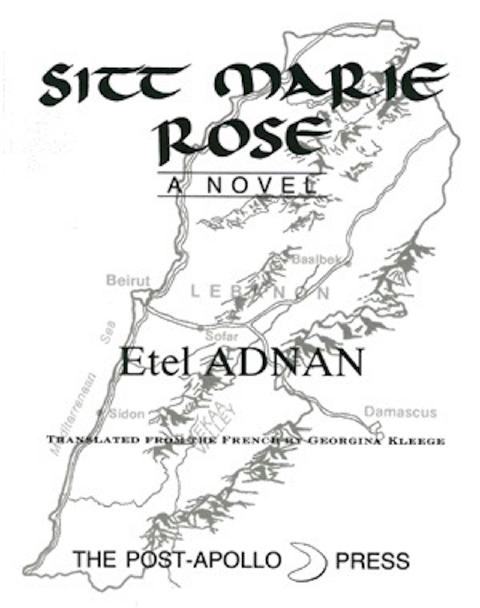

I want to recommend to listeners a novel by Etel Adnan called Sitt Marie Rose. It was written during the Lebanese Civil War, and already back then she was writing in these terms. She was saying there are these narratives that are causing so much mass violence. There was a line from the novel: “God, whoever you are, protect the future generations from the genocide that awaits them.” This was written back in the 1970s.

Etel Adnan & Sitt Marie Rose cover. courtesy of Wikicommons Media and Post-Apollo Press

EA: Etel was a pretty well-known Lebanese feminist and openly queer novelist and painter. Pretty remarkable person.

AT: I want to hear Naomi’s response — what you both said was so incredibly powerful. I just wanted to put it in the language of the end times fascism piece, because that piece is all about bunkering and how, in response to the recognition on the right that climate change is real, that the industries that create their wealth are Earth-destroying, population-destroying industries — AI, fossil fuels, the military-industrial complex — they’ve decided to bank on destruction. Literally, because it increases the amount of money in their bank account. But they also, of course, want to survive it, whether that’s in a literal vision of the Rapture because they’re religious, or if that’s a secular version, or if it’s going to be in their luxury bunker. The bunker is a major theme — the “bunker nation,” sovereign citizens bunkering.

What we’re talking about is the bunkering of stories. That’s what exceptionalism is. My story is separate from yours. Hearing you reflect, there’s a narrative dimension to this severing. And solidarity doesn’t thrive under those conditions. Solidarity is about reaching across difference, finding commonalities without erasing differences, so we can find allies and build that future where nobody has to endure a genocide.

These people are traitors — they are treasonous to this world and the wonders of this world. They’re not traitors to nation; they’re traitors to creation. That should fill us with righteous fury, a rage at the desecration of that project, and a fierce love for everything that is on the line — which is everything.

NK: Building on what Astra is saying, what surprised me in the research for the piece was that people in Silicon Valley, who are not primarily Zionists and might have no relationship with Israel whatsoever but are really interested in this bunkering project (sometimes they want to create their own private cities) — some of them refer to it as “tech Zionism.” They see the parallel very clearly.

Then there are people like Alexander Karp, who is the CEO of Palantir, who’s building all kinds of weapons for Israel and who clearly sees he is both a Zionist and a tech Zionist. It’s such an international project, and it is so porous in terms of the people we’re up against. We’re used to talking about it in a very linear way: These people are Zionists; they’ve adopted these policies because they want Israel to exist as it is. But we’re seeing it’s more than that: they actually want many Israels. This is how they bunker, and Israel is the ultimate bunker. And that’s why October 7 is the ultimate shattering shock, because it means the bunker is not holding, so they all lose their minds completely.

One doesn’t cancel out the other; it doesn’t mean Zionism isn’t an incredibly powerful ideology that is animating the project. But it’s important to also understand what Israel represents as a high-tech fortressed state “surrounded by enemies,” and if you can survive that, then you can survive the future. That’s their vision of what the future is going to look like.

The only other thing I was going to say in response to you, Dana: I understand it emotionally that if you’ve been subjected to the Palestine exception your whole life and been surrounded by people who claim to believe certain things — with an asterisk next to it, and that asterisk is you — it would make sense to respond to an exception with an exception.

DK: They’re sequestering themselves.

NK: It’s also an example of this mirroring and Doppelgangering we were talking about last time, which is just a trap.

EA: It’s a good segue, because I wanted to talk about bunkering—in the movie World War Z that came out some years ago, part of the plot is there is a zombie apocalypse; it’s an apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic world, and at some point this CIA officer and Brad Pitt go to Jerusalem and work with the Mossad and the IDF, because there is an invasion by zombies that are threatening to overtake Jerusalem. What the Israelis do in Jerusalem is create a fortress around it to keep the zombies out.

It’s not rocket science to see the metaphors, given there is an apartheid wall in Israel-Palestine in the first place. But this image: They are coming from the outside, these invading hordes, and what we need to do is ‘protect our own’ (and what they consider “our own” gets smaller and smaller). One thing that baffles me: it’s probably not good for my mental health, but I spend way too much time looking at what Peter Thiel’s bunker is supposed to look like and what these people have in mind for these underground bunker cities. Reading these and seeing the illustrations of what they imagine it would look like, the only thing I can think is, This will not work. This cannot function in the world rationally, objectively.

All my emotions aside, there is nothing in what they are building that is remotely meant to last.

DK: Or be human.

EA: Yeah. Even in their bunkerization, even when they think of future-proofing, they’re not doing a good job of understanding what makes a human human. The fact that they seem to have these difficulties in imagining what the world could look like in ten, twenty, thirty years, beyond a zombie apocalypse (just without the zombies) — weirdly enough, I find some hope in that. If their projects are doomed to fail, it gives me some mental space to think of what we can do in the meantime and not drag myself down too much in believing what they are projecting, what they think the world should be like.

I take it for what it is; it is a danger and a threat because of how it is affecting our world. But I don’t accept their conclusions as a given. For me personally, it allows me to have some mental flexibility or mental space to think: What can we do in the meantime to accelerate their decline, make them more irrelevant in the long term? What are the structural things we need to change? And what are the things that we need to create as an alternative regardless of their bunkerization?

NK: It’s very true, and it’s why it’s worth remembering what Astra was saying before: that this is first and foremost about the bank. It’s about the fact that their business models are incredibly profitable, and they’re addicted to this level of wealth accumulation, and they’re terrified — and I think there’s a way in which they can’t believe they’re getting away with it.

One of the things we came across in the research was the fact that Peter Thiel has said repeatedly that he believes the Antichrist is Greta Thunberg — which is a wild thing to say. But he has said it multiple times, and he explains that it’s because if Greta is right about what she’s saying, that we all need to ride bicycles (which isn’t what Greta is saying, but what he claims she is saying), this would require a One World Government that would be so repressive that that is what is foretold that the Antichrist is going to do.

Really all this is a window into the way his mind works. I really think they can’t believe they’re getting away with it, and they’re sort of waiting for us to stop them. I guess it’s another way we could try to find some hope: I really don’t think they believe that we’re not coming for them, which is why they’re coming up with these ever-more-bizarre fantasies about how they’re going to get away from us. We’re the zombies in this story.

DK: We’re always the zombies.

AT: They need to hide from the pitchforks in those bunkers, and they need an AI doctor because they don’t even want to risk having a real human physician. Naomi shared this amazing piece that was advertising one of these future shelters that would be equipped with a whole concierge service, including your robot healthcare.

EA: Good, good! Let them have the AI robots. That’s a good thing for us. They will not survive.

AT: We’ll see where it goes. But you brought up inevitability in your question just now. First you talked about inevitability on the left, the sense that we’re losing in advance, that things are inevitably getting so bad. We need to push back on that, because movements don’t happen overnight; we can look back on history and say there are lots of points where if people had just given up on the abolition of slavery or the enfranchisement of women, that would have looked like the rational thing to do. Where would we be today?

But these guys use inevitability in a different way. Part of the Silicon Valley marketing has always been: This stuff is happening, and you can’t stop it, and if you’re someone who’s trying to regulate it, you’re a Luddite and you’re anti-progress, because this is it! The locomotive of history is moving forward! And that’s bullshit. It’s not inevitable. It’s not inevitable that our destinies are to click on their ads all day.

Naomi invoked Walter Benjamin earlier. One thing he said was basically, “A revolutionary pulls the brake on the locomotive. We’re not doing this. It’s not inevitable. AI is real, but it’s also not what they’re saying it is.”

NK: I want to reiterate it’s not something anyone is asking for. It reminds me of the globalization debates in the nineties. They had to tell this story that would make people okay with the fact that the factories were closing in huge numbers and all the jobs were leaving. The story was there was going to be so much growth and the markets were going to expand and everybody was going to get rich. But they can’t tell a story like that about AI. They can’t, because we’re too cynical; nobody believes that. Nobody believes Sam Altman wants them to have a life of leisure where they’re going to get paid to make art. Why would they make art anyway? AI is making all the art.

This is why we try to bring some fire and brimstone to our article — to shake people a little bit. These people are traitors — they are treasonous to this world and the wonders of this world. They’re not traitors to nation; they’re traitors to creation. That should fill us with righteous fury, a rage at the desecration of that project, and a fierce love for everything that is on the line — which is everything.

DK: And each other.

NK: If this can’t wake up the left, I don’t know what can, honestly. We’re all tired, I get it. But it’s go time, like adrienne maree brown said. This is it. This is what we’ve all been preparing for, is this moment.

EA: What you just did is give me the perfect excuse to end my intervention with [James] Baldwin. He talked about how he cannot afford to be a pessimist. If someone like him (Octavia Butler, same thing) — he was literally the grandson of enslaved people and still managed to see through that and understand that the problem was not him; the problem was the society that was imposing this white supremacist vision of the world on him.

He said he cannot afford to lose faith — and even if you only know a handful of people who haven’t given up hope, that is still enough, that is still important, and you shouldn’t erase those people. Otherwise it would be a betrayal of many people, is how he put it.

What are certain things that do make you hopeful about the current world? If not specifically what is happening right now, are there concrete potentials coming out of the cracks?

AT: My answer is humble, in the sense that I take a lot of hope (to use your word) — I like the Mariame Kaba quote that hope is a discipline. It’s something you have to do every day; sometimes you’ve got to seek out your source. For me it’s the daily work of being part of the Debt Collective and seeing all these people — who I have a lot of respect for, who could be doing other things (some of them could be making a lot more money in other fields) — organizing every day. They’re trying to bring people in; they’re trying to build that welcoming left and to invite people in the door of our movement.

There are many days when I’m like, I don’t want to get on the damn Zoom. I would rather just doomscroll or eat soup. But I almost always feel better afterwards. This is why I think it’s so important for people to find a political home. Sometimes that daily glimpse of other people being good and doing good, and having that optimism of the intellect and of the will — actually putting that into practice — to me, that’s my source.

Every time I see people doing the work, I feel a bit better.

NK: I felt really hopeful when I was just at the Jewish Voice for Peace national membership meeting. It’s the first time they’ve had a national membership meeting, definitely since before the pandemic. There were two thousand people there, and it felt really defiant in the face of repression and criminalization, and it was about organizing in coalition for a breakthrough, and there were so many amazing people there. It felt strong.

I get a lot of hope from these kinds of unearthings — Elia, maybe you would call them hauntings — of the work of people who are uncovering lost histories so that we have more company, so that we’re able to draw on more sources of strength.

I also take hope from the fact that we have a richer diversity of voices than at any other point in human history to draw on. We’re drawing from the past because of this amazing time-travel research and unearthing that is happening in both traditional histories and also art, excavating buried art forms. When I was interviewing Anohni, the trans musician, she said, “At no other point in history would I have had a platform to be able to say these things. I would have been burned at the stake.”

I sometimes think about the fact that there are a lot of people now speaking who would have been burned, institutionalized, shut up, kept out. The work that you do with this platform is part of that. I don’t think it’s magic, I don’t think it happens on its own without the hard work of organizing, but we’ve never had more ingredients to throw in the pot.

AT: In the witches’ cauldron, it sounds like!

To your point, Elia, of appreciating progress even if it’s not the whole thing we wanted, and not always just pointing out the flaws and the lack and how far we have to go, but how far we’ve come — and thanking those ancestors who did this, who got us here — and building on it…

EA: I’m happy to plug a podcast that Margaret Killjoy does called Cool People Who Did Cool Stuff. It’s the answer to Behind the Bastards by Robert Evans (they’re part of the same network). It’s everything from alter-globalization movements, Zapatistas, to random heroes from two hundred years ago.

AT: I would love that.

NK: As a podcast addict, I can attest it’s great.

DK: Sorry to keep talking about this novel, but Sitt Marie Rose, as I said, written in the Lebanese Civil War — it was depressing to read, because we know what happens, we know these dynamics persist. But it was also gratifying to see somebody from across time recognize the same struggles that we are fighting and frame them in the same way. She even talks about how the fascist vision for the world, or for Lebanon in particular in this example, is one of making people disposable.

All the ways she articulates those things — it actually feels gratifying, empowering. It feels like you’re recognizing an ally across time, part of the unearthing you were talking about, Naomi. People should read that novel.

NK: Can I plug a novel? I’m a third of the way through it, and I’m loving it so much already. It’s Madeleine Thien’s The Book of Records, which is also about time travel and excavations. It’s an incredible book.

EA: If we’re plugging fiction, I have a podcast on Star Trek that we launched yesterday called Resistance is Fertile with carla joy bergman, who’s also a good friend and an amazing author.

AT: Oh wow! Say hi to her for me.

EA: Will do.

It’s a play on words that’s thematically relevant to what we’re talking about, because one of the alien species in Star Trek, the Borg, says “resistance is futile,” as they absorb other civilizations. We’re going to explore Star Trek episodes; it’s very much a conversation about the political importance of storytelling, and anarchism, and fun stuff in between.

DK: I’ve got to catch up on Star Trek. I missed the boat on that one.

EA: That’s okay.

Astra, Naomi, thank you so much for being on the podcast.

AT & NK: Thank you.