Introducing The ‘Tuers’: Translations from Doyres Bundistn, Part 2: Ephraim (“Frank”) Zalman Atran

Translator’s Introduction:

I am pleased to be continuing my series of translations from Doyres Bundistn, “Introducing the ‘Tuers,’” with the entry of Ephraim (“Frank”) Zalman Atran. While this installment only features one individual, his story presents a great deal to dig into. A barricade fighter who was shot three times in 1905, an anti-Bolshevik Bundist who fled the Cheka in the early days of the Soviet Union, a businessman in France, and eventually a multi-millionaire ‘champagne Bundist’ philanthropist in America, the strange arc of Atran’s life takes us all the way from Smila, Ukraine in 1885 to 1950s New York. On a smaller note, the entry contains interesting turns of phrase such as ‘the United States of North America’ which is oddly reminiscent of terms like ‘USAmerica’ today.

In addition to Jacob Sholem Hertz’s typical historical narration, the entry quotes at length from papers in the Bund’s archives, and publications like the Forward, Der Tog, and Undzer Tsayt. The range of publications included speaks to the interaction between the Bund and the labor movement in Europe and the United States, as well as the influence of Atran specifically on the landscape of American Judaism beyond the Bund’s sole purview. The quotes from Franz Kursky’s letters are also of particular interest. Kurksy was the keeper of the Bund’s archives for a time and one of the most significant tuers within the Berliner Gruppe Bund.

Individuals like Atran provoke questions of what it meant to be a Bundist and a businessman; Raphael Abroamovitch grapples with this question in his reflection on Atran after the former’s death (also quoted at length below). Atran’s life was full of change and contradictions, from his youth as a young man from a religious household caught in a secularizing wave, to his time as a revolutionary and an anti-Bolshevik, until his return to business after fleeing the Nazis, unable to fully leave behind the labor movement.

You can read the first installment of Tuers here.

Introduced and translated by Sam Miller Hirshberg.

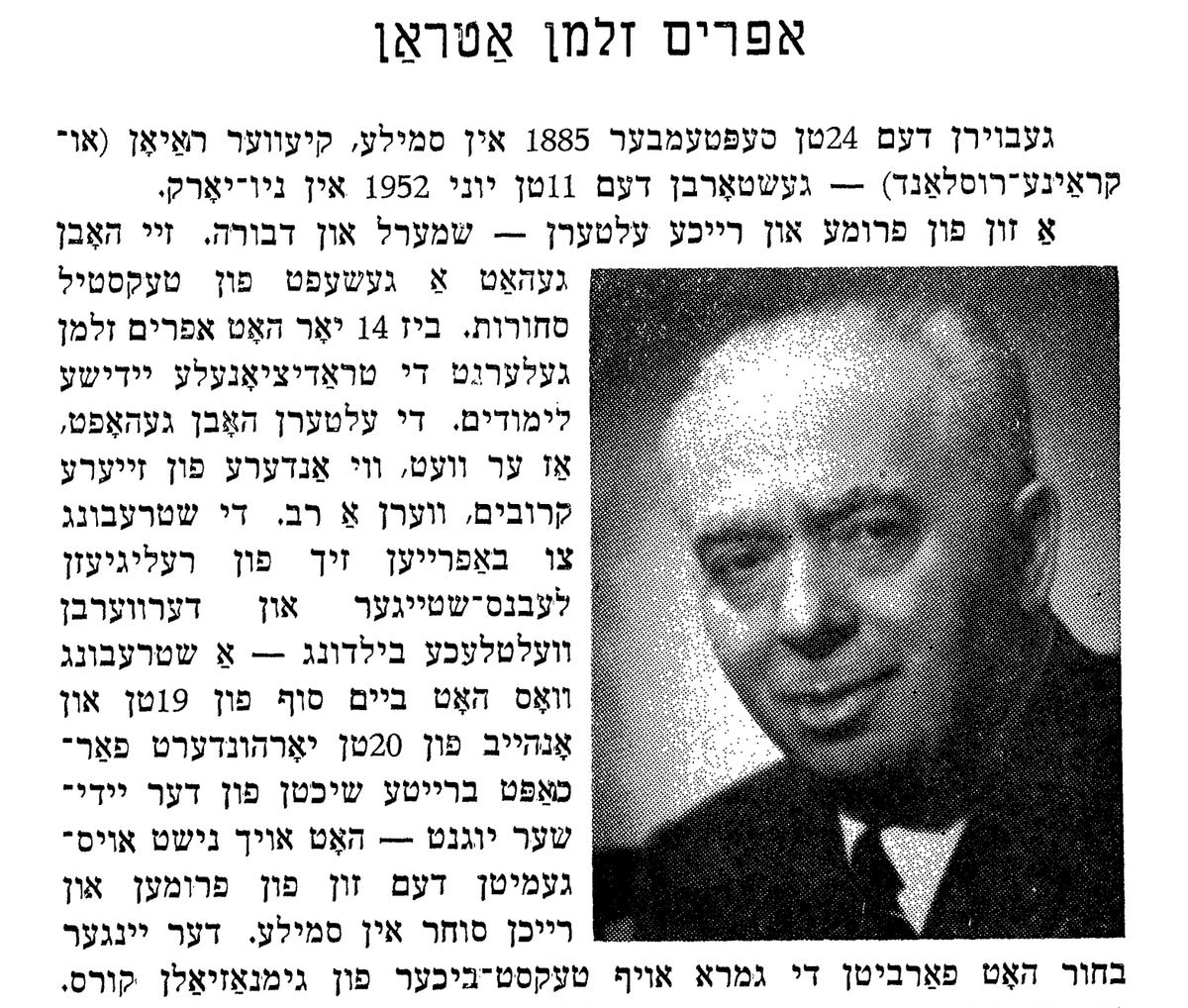

Ephraim Zalman Atran

Born on the 25th of September 1885 in Smila, Kiev region (Russian-Ukraine) – Died the 11th of June 1952 in New York.

A son of religious and wealthy parents– Shmerl and Dvoyre. They had a textile goods business. Until the age of 14, Ephraim Zalman was taught traditional Jewish subjects. His parents hoped that, like some of his other relatives, he would become a rabbi. The struggle to free oneself from a religious life-style and acquire secular education – a struggle which had by the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century seized wide swathes of the Jewish youth– had also succeeded in reaching this son of religious and wealthy merchants in Smila. The young bocher exchanged the Gemara for textbooks from a gymnasium course. As an unmatriculated student, he studied for the exam which would allow him to attend university.

To see his plan through to completion, he decided to abandon his small provincial town and settle in a large city. He chose the factory-town of Łódź, in Poland, where an uncle of his lived as a textile-merchant.

In Łódź, his plan of study collapsed. Atran came to work in his uncle’s business. He set his textbooks aside and gave his attention to the textile goods trade and in doing so exhibited good business skills. It wasn’t long before he was a partner in the business. The path of a merchant career was open to him. Yet he did not go far down this path.

The Jewish labor movement, led by the Bund, expanded widely throughout Łódź in the first years of the 20th century. Thousands of weavers and workers of other trades revolted against the oppression of tsarism and against the established antiquated order of Jewish life. They lived through a social and national awakening. As a rule, merchants and manufacturers were enemies of the revolutionary socialist movement. However, in the case of the practical young merchant, Ephraim Zalman Atran, dry calculations and business plans emerged parallel to Atran’s purer idealism. The self-sacrificing struggle of the Jewish worker allowed him no peace. In 1904, at the age of 19, Atran took a further radical step: he joined the Bund.

The revolution came in 1905. Atran left business and threw his heart and soul into the Bundist movement. The proletariat of his large factory-town stood in the front ranks of the revolutionary struggle against hated Tsarism. The workers paid a price in blood and life in the struggle for freedom. Atran also gave his share. He was a participant in various revolutionary uprisings and he did not avoid the enemy’s bullets either.

In the summer of 1905, stormy demonstrations and a bloody barricade fight occurred in Łódź. During the barricade fight (in the second half of June 1905), Atran was wounded in both feet. Friends carried him away from the battlefield and hid him, so that he would not fall into the hands of the Tsarist police.

He was taken to Berlin, where he was to be operated on to remove the three bullets which remained in his feet. A letter which Franz Kursky wrote on the 27th of August 1905 in Berlin to the Foreign Committee of the Bund in Geneva reads: “With a comrade from Łódź, who travelled here to have bullets removed, who I was already acquainted with. A person after my own heart. Two bullets in one foot, one in the second. The bullets will stay. An operation is not necessary. The bullets are not harmful. In the course of a month he will be well. Two bullets are from a soldier, one from a revolutionary, ours (!), due to a mistake.” Kursky writes further: “He dictated to me and I wrote a true account of the first two days of the Łódź uprising.” (The description was printed in the Berlin newspaper of the German Social Democrats– Vorwärts).

In the interest of caution so that the Russian Police’s spies would not find out about him and report him to the Ukhrana [Russian political police; probable forgers of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion], he was admitted to a Berlin hospital (Königliche Charité) under the false name Beno Rozen. They operated on him, but one bullet was not removed and it remained in his foot until the end of his life.

When Atran was released from the hospital, he returned to Łódź. He was confined to crutches for a rather long time afterwards.The reaction had worsened and it was dangerous for the wounded revolutionary to stay longer in Łódź. This sent him back to his hometown, where he was active still in the local Bundist organization. When Tsarism finally succeeded in choking the revolutionary movement, Atran returned yet again to trade in the textile business.

The revolution came in the year 1917. Atran liquidated his business a second time and threw himself with full force into the Bundist and Social Democratic movement. He built organizations, participated in congresses, was active in the worker-councils, in the election campaigns, and in various other actions. He was active in Kiev, Moscow, Samara, and other places.

After the Bolshevik coup, Atran found himself in the camp of socialists who saw the coup as a calamity. He himself narrowly avoided arrest at a Bundist meeting in Moscow, which was attacked by a detachment of the Cheka. At the meeting Atran talked about an anti-Bolshevik uprising in Samara—the reason for his having left the city. While the Chekists attacked the hall, Atran and two other comrades happened to have gone out to drink a glass of tea and therefore were saved while the other Bundists were arrested at the assembly (the meeting took place on the premises of the professional party of printer-workers, which was in opposition to Bolshevik power).

For about 8 years Atran lived under the Bolshevik regime. He saw it for himself up close, as well as the suffering and the denial of basic rights to the popular masses. He could not make peace with it and he could not adapt. He began to think about leaving Russia, leaving in 1925.

In Berlin he was connected with an international sock company: Etam. He became a partner and set up a number of textile enterprises for the company in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg.

In 1940, when Nazi German armies took Belgium and France, Atran left for the United States of North America. Here, he became known as Frank Z. Atran. At the end of the Second World War he returned to Europe, where he took back the factories and businesses the German Hitlerites had stolen. Afterwards he returned to America. Here, as in Europe, he continued to lead his large businesses and became a multi-millionaire.

Despite his great wealth, he never forgot his origins. He continued to hold onto his ideological connection with the Jewish and Russian socialist movement. He never cut the threads of friendship and connectedness with the ideals to which he had dedicated his youth and for which he had spilled blood. The great fortune never blinded him and was never capable of leading him away from his humility. People used to see him often at different great undertakings of the Bund and other socialist organizations in New York. He never fought for a seat at the head of the table. For many years he also materially supported the organizations, to which he felt an ideological closeness. In New York he became a member of the Bund Organization, the Erlich-Alter branch of the Worker’s Circle and other organizations.

In the last years of his life, he decided to give away great sums of his fortune to social causes. He did this through the Atran-Foundation which he had established in 1945. It continued to give away great sums after his death and continues to do so to this day. In 1950, the foundation gave a million dollars to the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York to build up a laboratory for medical and scientific research. In January 1952, the foundation bought a house in New York for 200,000 dollars especially for the Jewish Labor Committee, Bund, Jewish Culture-Congress, and related institutions. In February 1952, the foundation established in Columbia-University (New York) an endowed professorship for the Yiddish Language, literature, and culture and contributed a quarter million dollars towards this aim. During these years the foundation divided significant sums between dozens of organizations and institutions – Jewish and non-Jewish.

In December 1926 Atran was married in Kovne (Lithuania) to Zhenie Dimentshteyn, a daughter of lawyer Leopold Dimentshteyn.

Ephraim Zalman (Frank Z.) Atran died after a long illness on the 11 of June 1952 in a New York hospital. His wife – a few years later.

After Atran’s death R. Abramovitsh wrote about him: “In the capitalist world, a minor employee, a Bundist, does not become a multi-millionaire just like that, simply by chance.” … “In modern society, to struggle and succeed in amassing a great fortune—and this also means great power—a young person must have special abilities: a lot of dreams, intelligence and above all a strong and steadfast character, an iron will and an extraordinary amount of energy. It was certainly not the aim of the ‘Bund’ to raise future businesspeople, successful manufacturers, future great merchants, doctors, professors and engineers, but unintentionally we in the ‘Bund’ had in those years awakened a whole stratum of Jewish people to social life and nurtured the best and most able with social energy. A powerful storm stirred up the ocean of humanity, and even decades after the storm, small human waves still vibrate and swirl—each with their own path, continuously loaded with energy which they had absorbed from a great, liberating storm. In those years, thousands of people within the movement mastered how to contribute with their own talents and gifts. They understood their power, their influence on other people and society.”

“So it was that we had, unintentionally and unknowingly, nurtured a generation of future civic and even business talents. The late Atran was one of them. He had a superhuman energy, really a dynamo-machine, who unceasingly worked with full force and carried other people with him. He possessed every personal magnetism, which is immensely important for success in life. People found themselves drawn to him. He had aside from this a lively and sharp interest in politics, and entirely and correctly understood confusing political and strategic problems.” (Forverts, 17 June 1952)

It can also be added here that with Atran, the multi-millionaire, our social conscience stayed awake. This pressured him to create his foundation, and for several years before his death, he used to say: “I remain at least 50 percent socialist.” He never lost the idealism which had in his younger years guided him to the ranks of the Bund and to the barricade fights of Łódź.

Bibliography: Manuscripts of the Bundist Archive. Tsviyen: Forverts, 12 January and 15 March 1952, New York. A. Glants: Der Tog, 12 March 1952, New York. P. Berman: Forverts, 30 March 1952. R. Abramovitch: Forverts, 17 June 1952. E. S.: Undzer Tsayt July-August 1952, New York. A. Y.: Yearbook of the Cemetery Department – Workers Circle 1953, New York. Workers Circle builder and tuer, New York 1962.

J. S. Hertz.

Trans. 2025 Sam Miller Hirshberg