The Zionist War on Yiddish in Palestine

Editor's note: This is a version of Elia Ayoub’s Master’s thesis about the war on Yiddish in Palestine written in 2016, graciously abbreviated and adapted for publication in Der Spekter. Source citations have been changed to links for easier reading. To read the original full essay with citations, please visit and support Elia’s newsletter, Hauntologies.

In January of 1945, a well-known heroine of the anti-Nazi resistance in the Vilna ghetto, Ruzhka Korchack, was invited to a conference in what would become Israel to speak about her experience fighting the Nazis. Being a Jew from Lithuania, she spoke the language of Eastern European Jews: Yiddish. While her speech was well-received by the audience, another speaker came after her and complained of the language she spoke in, calling it “a foreign, grating language” in Hebrew. So shocked were members of the audience that that speaker was “prevented from finishing his speech by outrage in the auditorium.” This becomes all the more surprising when it is revealed that the man who seemed obsessed with an anti-Nazi Jewish partisan fighter’s choice of language, her native language and that of millions of Ashkenazi (of European origins) Jews, was none other than David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister. Even more troubling is the fact that Ben Gurion, born David Grün in Płońsk, Poland, was himself a native Yiddish speaker.

Ben Gurion wasn’t the only Zionist to have held such a negative view of the Yiddish language, or indeed even an exception.

In fact, Zionist hostility to Yiddish was the norm. So common was the conflict between the Hebraists, those advocating for the Hebrew language, and the Yiddishists, those advocating for the Yiddish language, that some scholars, like the Israeli-American literary critic Hillel Halkin, called it “one of the great Kulturkampf, the non-violent civil wars, of Jewish history.”

"Many of those involved in advocating for Yiddish as a recognized language of the Jewish people saw their opponents as those advocating Hebrew as the sole language of the Jewish people"

Halkin, in a 2002 article for Commentary, recounts how, in his youth, his father got angry at a Jewish woman because she was speaking Yiddish. Halkin later understood that his father’s bitterness was part of a “language war between Hebrew and Yiddish, itself part of the great cultural and political conflict between Zionism and ‘Diasporism’ that sundered the Jewish world in the first decades of the 20th century, and that ended only when an even greater conflict left the European Diaspora in ruins beside a newborn state of Israel.” He learned from his father that Yiddish, while “admitted to our home every morning with the milk bottles like a servant given the run of the house,” was his enemy despite the fact that multilingualism was a reality to most Jews in Palestine.

Language played a crucial role in defining the Zionist ideal. Many of those involved in advocating for Yiddish as a recognized language of the Jewish people saw their opponents as those advocating Hebrew as the sole language of the Jewish people, and vice versa. Given the context of pre-World War II politics, this also meant a certain intersection between these debates and debates on capitalism and socialism as well as diasporism, nationalism and internationalism.

Why choose a formerly ‘dead’ language, Hebrew, instead of the language of the majority of Jews before the Holocaust, Yiddish? And what of today? What does the language Kulturkampf mean for contemporary debates on Zionism? What do they allow us to conclude, and how are they, or how can they be, used by Jewish activists in Israel and, especially, in the diaspora in the West who are struggling for justice in Israel-Palestine today?

The Great Kulturkampf: Linguistic Fascism in the Land of Zion

The anti-Yiddish attitude prevalent among Zionists translated itself into what Israeli scholar Avi Lang called “linguistic fascism in the land of Zion.” Lang notes that “family lore in most Ashkenazi households in Israel will almost inevitably include stories of grandparents and great-grandparents experiencing discrimination whenever they spoke Yiddish in the streets of 1940s and 1950s Tel Aviv,” which included being “hit or spat at.” The American Yiddish scholar and translator Yehoash, who moved to Palestine in 1913, wrote in 1923 that “Yiddish [in Tel Aviv] is taboo. To speak Yiddish in public requires the utmost courage.” And a flier in (ironically) Yiddish distributed in the late 1930s read, “Learn Hebrew! Every Jew in Palestine, whether he has just come or whether he is a longstanding resident, must speak and conduct all his business in the old-new language of the Jewish people: Hebrew.”

Even more notable was the presence of organizations dedicated to enforcing the Hebrew language on the streets of Palestine, such as the “Battalion of the Defenders of the Hebrew Language” in the 1920s, the “Organization for the Enforcement of Hebrew” in the 1930s, the “Central Council for the Enforcement of Hebrew” in the 1940s, as well as the “Cultural Committee of the Jewish National Council.” As Hebrew and Arabic literature scholar Lital Levy asserted, “It was not even the state that created the language so much as the language that created the state.” Hebrew, seen through this lens, was not just a component of the Zionist state-building project but one of its fundamental tenets.

In such an environment, it is no wonder that Yiddish in Israel today is, in the words of Israeli scholar and critic of Hebrew literature Gershon Shaked, “a dead language, used mostly in homes for the elderly and as a literary language by a few Holocaust survivors.” While, indeed, Yiddish is kept alive in some homes in Israel and across the diaspora, namely religious enclaves like Williamsburg, New York, we can safely say that Yiddish today no longer holds the same centrality to (Ashkenazi) Jewish life as it did less than a century ago. The combined forces of the Nazi Genocide (up to 85% of the people killed in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers), Stalin’s persecution of Yiddish writers, the cultural assimilation of North American Jewry (less than 200,000 Yiddish speakers as of 2011 out of over 5,000,000 American Jews, 90% of whom are Ashkenazi and therefore descendants of mainly Yiddish speakers), and Israel’s language policies all left Yiddish in a very weak position by the 1950s.

Bundist diasporism versus Zionist nationalism

The conflict described as between Zionism and what has come to be known as “diasporism” can be traced to the early decades of the 20th century, when a dominant force within European Jewish politics was the largely Yiddish-speaking, largely anti-Zionist or non-Zionist Jewish Labour Bund, also known as the Bundists.

When examining Bundists’ attitude towards the Hebrew language, one thing comes across as striking: Bundists, American Jewish scholar Ezra Mendelsohn writes, were often “leftists [who] were likely to attack the holy language [Hebrew] as a tool of reactionary, obscurantist clerics.”

As a democratic socialist party committed to maintaining secular Jewish culture, particularly the Yiddish language, the Bund became one of the most important left-wing Jewish organizations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Bundist concept of doikayt, a Yiddish word meaning “here-ness,” was crucial in that it “called on Jews to foster Jewish culture wherever they live.” It can be argued that ‘doikayt’ was one of two ways of tackling the “‘Jewish question” — the question of European antisemitism at the time — that did not involve full assimilation. The “Jewish question,” the Bundists argued, should be solved “here,” where already we live, and not “there” — in Palestine or some other place where European countries could offload their “Jewish problem.” But other Jewish thinkers saw the answer to the Jewish question as one which cannot be “here.” Their advocacy of a necessary ‘there-ness’ came to be known as Zionism.

Highlighting Bundist-Zionist tensions seems all the more relevant given that both the Jewish Labour Bund and the First Zionist Congress were launched in the same year: 1897. The date is not coincidental: it came three years after the beginning of the now-infamous “Dreyfus Affair,” which lasted until 1906. The injustice imposed on Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer of Jewish descent wrongfully accused of treason, is credited as one of the factors that influenced Theodor Herzl, the political founder of the Zionist movement.

Herzl’s anti-assimilation position was expressed in his famous 1896 “The Jewish State” pamphlet as such:

“[I]f France – bastion of emancipation, progress and universal socialism – [can] get caught up in a maelstrom of antisemitism and let the Parisian crowd chant 'Kill the Jews!' Where can they be safe once again – if not in their own country? Assimilation does not solve the problem because the Gentile world will not allow it as the Dreyfus affair has so clearly demonstrated.”

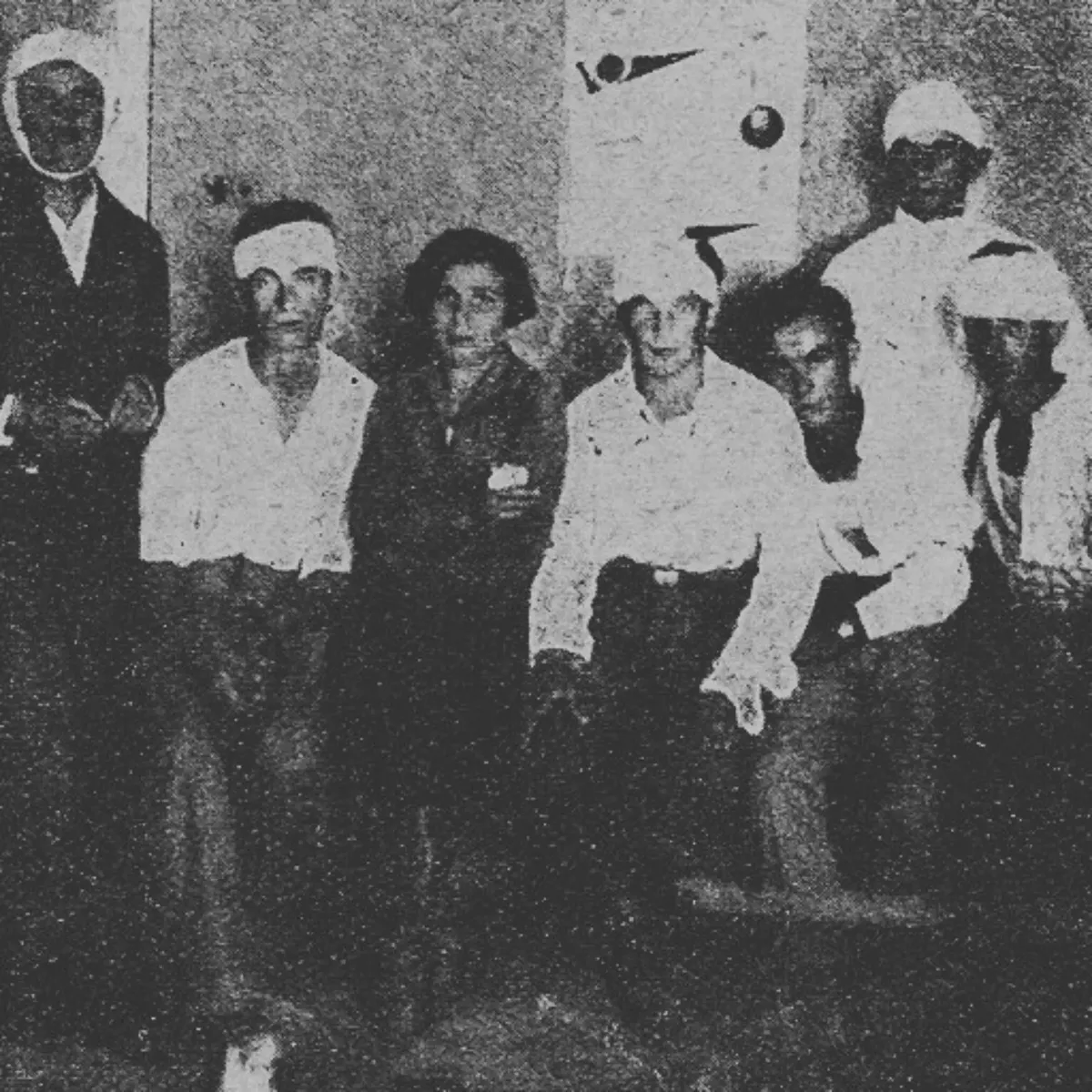

We see the differences between class-oriented Bundism and nationalist-oriented Zionism early on. For example, the Bund defended the Palestinian riots of 1929 as an “anti-colonial uprising, rather than as anti-Semitic, as had been depicted by Zionists.” Even the Bundists who ended up going to Israel-Palestine seem to have done so out of necessity rather than conviction. As a 90-year-old former Jewish Labour Bund member, Yitzhak Luden said in a Yiddish Community Center in Tel Aviv in 2012, “I came to Israel in 1948 not as a Zionist, but as someone fleeing war-torn Europe [...] and the few Bundists who came made clear our political position in support of Palestinians, and for a one state solution.”

Zionism: a nationalism unlike any other?

In its simplest form, Zionism is a political movement that emerged in late 19th-century Europe and sought to establish a Jewish state as an answer to European antisemitism, culminating in the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.

Polish historian Dr. August Grabski set out to list four elements said to define Zionism:

- “The primacy of the Jewish community in Israel over Jewish communities around the world;

- “The primacy of Jews over Palestinian Arabs within the borders of the former colonial mandate in Palestine;

- “The elevation of ethnic-religious conflicts over class conflicts;

- “Attributing to Hebrew the status of being the main or even only national language in Palestine.”

In Zionism, Benedict Anderson’s concept of an “imagined community” is evidently at play. Zionists sought to put forward the notion that Jews are a distinctive “people,” a nation, linked to one another through a common ancestry, as opposed to “just” a religion or an ethnicity. Thus, a French Jew is linked to an Ethiopian Jew, who is linked to an Iranian Jew. What “primarily” defines them is not their “French-ness,” or “Ethiopian-ness,” or “Iranian-ness,” but their “Jewish-ness.” This, Zionism shares with other contemporary nationalist movements and diaspora communities who perceived themselves as such. Jews were, in the words of British historian and political scientist Hugh Seton-Watson, a “diaspora nation.”

But Zionism also presented a unique feature that separated it from other European nationalist movements: the Jewish return to a former territorial homeland, as opposed to a struggle for liberation or territorial secession, an anomaly that prompted such Jewish thinkers as Hannah Arendt to describe Zionism as “the nationalism of those people who had not participated in national emancipation and had not achieved the sovereignty of a nation-state.” This is in addition to the fact that, for Zionist Jews, the “homeland” was not always well-defined; the “homeland” was something to escape to, an answer to a very European problem: antisemitism.

Zionism’s “other”: contradictions and paradoxes

The creation of a new Jewish identity under Zionism necessitated the presence of an identity that it could emulate or relate to and an “other” that it should discard. For Zionists the identity to be discarded was clear: the “diaspora Jew,” the Jew facing antisemitism in the West, who was viewed as “culturally stagnant, passive and backward.”

The European Gentile, the very source of the antisemitism that prompted Jews to turn to Zionism as a solution in the first place, on the other hand, became the identity Zionists wished to emulate. Putting it in a different way, the oppressor was to be emulated while the oppressed was to be discarded as a weak and dying breed. In its most extreme form, Zionists viewed Jews dying in the Holocaust as “sheep to the slaughter,” a memory that has endured in Zionist culture, and especially in Israel itself.

Confronting the perceived “weakness” of the Diaspora Jew was the idea of the “Sabra,” named after a desert cactus, the name used to describe all Jews born in Israel, representing around 70% of Israel’s Jewish population today. Instead of being “weak and effeminate” like the Diaspora Jew, the Sabra Israeli Jew would be “an ideal of Jewish muscular masculinity.” Some Zionists even suggested replacing the “weak” word “Jew” with the stronger-sounding “Hebrew man.”

Redeeming the Jews required an “other” through which Zionists could build and mold their own identity, not unlike how Europeans “othered” the “Orient” or the “East,” as explored by Edward Said in his seminal book Orientalism. That “other” varied with time but eventually succeeded in “Westernizing” all Jewish Israelis — whether they were Ashkenazi, Sephardic or Mizrahi — while orientalizing Palestinians.

Arab Jewish scholar Ella Shohat reflected on this contradiction inherent to Zionism: rather than the supposed centrality of a “return” to supposed Middle Eastern origins, the paradox embodied in the State of Israel is that it is “ideologically and geopolitically oriented almost exclusively toward the West.” In other words, rather than “‘end a diaspora’ characterized by ritualistic nostalgia for the East,” Zionism produced a state of permanent hostility towards the “East.”

Erasing Palestine and “Hebraizing” the Land: Building an “Image of Antiquity” with the “Old-New” Language

In creating the new Jewish Zionist identity, Zionists then needed to choose a national language, which brings us to the Hebrew-Yiddish debate and why Hebrew was designated the “true” language of the Jewish people.

Beyond its practicality as the lingua franca of a multilingual world Jewry, Hebraists argued that Hebrew would allow Jews to start anew. Since they are changing their lives radically in order to build a new one in a new land, wouldn’t it make sense to have a “new” language with it? And what could be more appropriate than the ‘old-new’ language of Hebrew, which can serve as both a link to a mythical past and the needs of the present?

“For early Israel,” Lang writes, “Yiddish stank of the ghetto; it was the demotic of the persecuted, the victim, the murdered” in contrast to the ‘strong’ Hebrew-speaking Sabra. In order to achieve this identity, “the Zionists needed to erase existing ethnographic textures, forget specific histories, and take a flying leap backward to an ancient, mythological and religious past,” writes Shlomo Sand in The Invention of the Jewish People. This did not just involve the hegemony of the Hebrew language as the sole language of the Jewish people, but it notably included the practice of archeology in the service of the nation-state.

In addition, the new identity had to be consolidated through the national education system. For example, the way Palestine is portrayed in Israeli schoolbooks is one in which the very existence of a historical Palestine is denied, which parallels the way in which archeology is used. In a 2012 study, Nurit Peled-Elhanan argued that the textbooks she studied “harness the past to the benefit of the Israeli policy of expansion, whether they were published during leftist or right-wing [education] ministries.” After analyzing dozens of textbooks, she could not find a single “photograph of a human being who is Palestinian.” Instead, all that can be found are Palestinians as “the problems and threats Israel considers them to be,” portrayed as “terrorists, face-covered figures; or as primitive farmers; or in racist cartoons,” Peled-Elhanan told AlternateFocus in a 2011 interview. This policy can be seen as part of the wider ethnic cleansing of Palestine from its inhabitants, which reached its peak in the 1948 “Nakba,” the date Israel declared independence and oversaw the mass expulsion of over 700,000 Palestinians.

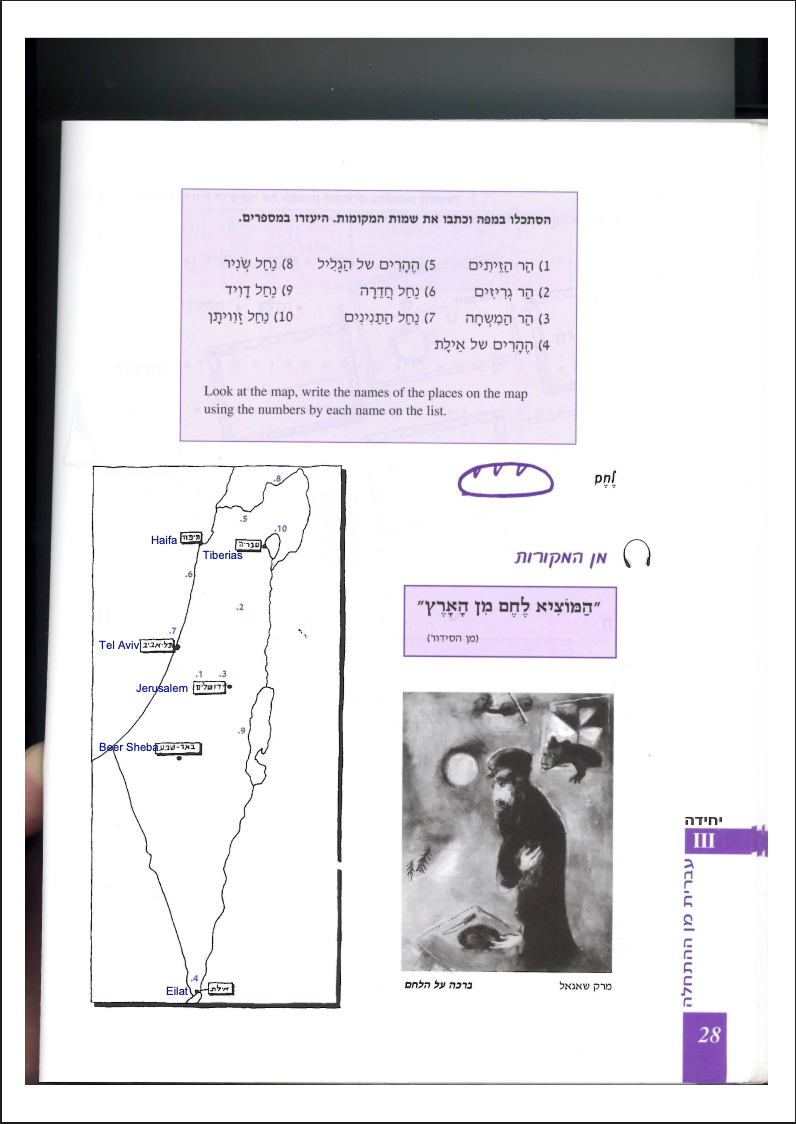

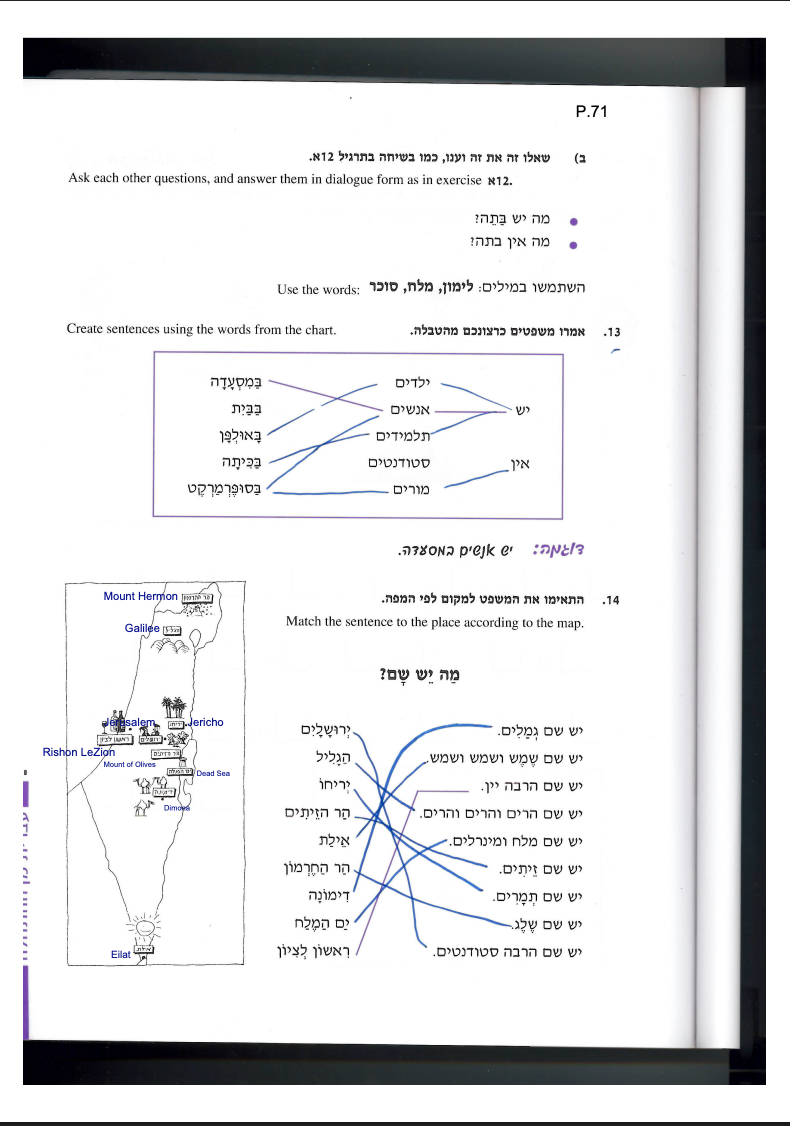

I can personally confirm Peled-Elhana’s assessment after taking an elementary Modern Hebrew course at SOAS in 2015-2016. Looking at the maps in the “Hebrew from Scratch: Part 1” textbook alone is revealing for the simple reason that, according to the Israeli Ministry of Education, schools choose textbooks only from an approved list, meaning the maps shown are government-approved. In the six instances in which the map of what should officially be the State of Israel and the State of Palestine is shown, the latter is completely absent. Later in the textbook, one can see Jericho and the Mount of Olives, both in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, as well as Jerusalem (no distinction is made between the Israeli West of Jerusalem and the Palestinian East) as part of Israeli territory, and the Gaza Strip is absent altogether. Indeed, the maps give the impression that Palestine never existed and, by extension, neither did Palestinians.

Pages from "Hebrew from Scratch: Part 1." Courtesy Elia Ayoub.

The need to deny Palestinian-ness should be understood as part of Zionism’s inherent obsession with demographics. This means that while the ‘product’ of Palestinian-ness can be utilized, it can only be done by denying its origins. To this day, we see the effects of this ‘Judaizing’ principle. For example, the Israel Land Fund, which erases both Gaza and the West Bank on its website, encourages purchasing properties in Arab-majority East Jerusalem “for the purpose of settling Jews there.” Carried out in tandem with Palestinian dispossession, these policies are further implemented through the renaming of places using Hebrew signage.

A New Kulturkampf? Zionism versus Diasporism Today

"For many, learning Yiddish is a political statement of defiance that has come to represent the opposite of what Hebrew has come to represent"

In 2009, the Moses Mendelssohn Centre in Berlin hosted a conference entitled “European Jewry: A New Jewish Centre in the Making?” in which two possible futures for Western Jews were listed: Diasporism or Cultural Zionism. We can say that these two competing alternatives represent a modern Kulturkampf, though not by any means the only one. Fundamentally, the two positions differ greatly on the relationship between Jews and non-Jews. Avraham Burg, former speaker of the Israeli Knesset, recently wrote, “I maintain that [...] [Diaspora Jews] created a situation in which the goy can be my father and my mother and my son and my partner. The goy [in the West] is not hostile but embracing. And as a result, what emerges is a Jewish experience of integration, not separation. Not segregation. I find those things lacking [in Israel]. Here the goy is what he was in the ghetto: confrontational and hostile.”

Just as Zionism had to embrace a number of contradictions to survive in uncertain conditions, so do many Jews rejecting Zionism today. Just as Hebrew became synonymous with Zionism and the creation of a ‘new Jew’ in what ended up becoming the only Jewish state, so did Yiddish come to represent the language of anti-Zionism and Jewish diasporism, often entering the realm of internationalism. So what Yiddish really ‘is’ is not as pertinent as how it is perceived by a growing number of young and disillusioned left-leaning Jews.

This is why, for many, learning Yiddish is a political statement of defiance that has come to represent the opposite of what Hebrew has come to represent. As Avi Lang describes, “Hebrew is the language of power, Yiddish is the language of pacifism, and where Hebrew stands for Zionism, Yiddish stands for internationalism.”

The growing rift between Israel and American Jews

The recent phenomenon of (non-Orthodox) Ashkenazi Jews learning Yiddish is in many ways the result of a growing rift between the Israeli government’s policies and the politics of primarily young American Jews, the country with the largest population of Ashkenazi Jews (exceeding Israel’s Ashkenazi population). If we compare trends in Israeli politics with the progressive tendency among young American Jews, we notice striking differences. A 2021 Pew Research Center study showed that 37 percent of young American Jews (18-29) believe that the United States is far too supportive of the Israeli government, as opposed to 22 percent of all Jews, and only 35 percent of Jews in the same age bracket said caring about Israel is “essential” to their Jewish identity as opposed to 45 percent overall.

While its domestic policy is often criticized, it is Israel’s occupation of Gaza and the West Bank that has provoked the largest Jewish opposition. Indeed, Netanyahu’s government is now commonly called the “most right-wing nationalist government” in the state’s history, and includes notorious politicians such as Itamar Ben-Gvir, leader of the Kahanist anti-Arab party Otzma Yehudit (“Jewish Power”) and a former defense lawyer for suspected Jewish terrorists. The same 2021 Pew study indeed found that less than half of American Jews had a favorable opinion of Benjamin Netanyahu, and this trend has only continued since the start of Israel’s genocide in Gaza in 2023.

A striking point illustrating the growing rift between American Jews and Israel is how often ads produced by the Israeli Ministry of Immigrant Absorption are criticized by the American Jewish community. In 2011, the ministry released an ad “intended to tug at the heartstrings of Israelis living outside the Jewish state,” which instead provoked outrage for its hostile depiction of the relationship between Jews and non-Jews. The ad showed a girl talking to her grandparents in Israel in Hebrew when her grandmother asked what holiday it is. To everyone’s disappointment, she replied “Christmas” despite having a Hanukkah menorah in the background. The message is clear: Israeli Jews outside of the state of Israel forget what it means to be Jewish and can only be reminded by going back. This belief is perfectly exemplified by the word used to describe Jews immigrating to Israel, namely aliyah, which means “ascent” in Hebrew. Jews who leave Israel to settle elsewhere are said to make yerida, or “descent.” Taken literally, this would mean that any Jew not living in the land of Israel is at a lower level than those who do. When comparing this hostility towards the Jewish diaspora with Burg’s statement that in the West, the goy is embracing, the difference is striking.

This anti-diasporism was further explored in a documentary by Israeli-French director Eyal Sivan entitled “Izkor, Slaves of Memory,” an excerpt of which is available on YouTube. Sivan takes us through the Israeli education system from the very young up to the time students graduate and join the Israeli army. Throughout their education, we see the constant presence of a fear that is being reproduced in each history class: the fear of the state of diaspora. The teacher featured in the excerpt tells her students that only by “ascending/immigrating to Israel can Jews find freedom.” Here, we see history being used to serve the purpose of nation-building by going back to this ancient, mythological and religious past.

Diasporism and the potential for radical politics: the case of alternative Hebrew schools

A group I would argue is aware of the politics of the Hebrew language and is attempting to struggle against what it views as its current dominant oppressive dimension is the Tel Aviv-based ‘This is not an ulpan’ (TINAU) group. The name itself is revealing, given the fact that the ulpan, an institute or school dedicated to the intensive study of Hebrew that, for Jewish immigrants to Palestine, “acted as a first step toward navigating their way through a foreign country and integrating into a new society” according to a 2016 article, a role it still serves today. Indeed, according to the group’s website, “we don't learn Hebrew, we learn in Hebrew.” What they mean by that is that they advocate learning Hebrew as a language stripped of its usual compulsive ideological component. When I interviewed one of TINAU’s co-founders, Daniel Roth, he explained that this simply “refers to the idea that each of our classes is 'about something else.' So, for example, we will learn about Israeli politics in Hebrew, thereby learning about politics and gaining experience listening, reading and debating in Hebrew.”

These Hebrew-language schools challenging the Zionist narrative are relatively new, which explains why scholarship on the topic is still light. But the phenomenon has been picked up by a number of publications and websites. In June 2016, Roth told the Israel-based +972Mag that he was looking for an alternative to the typical ulpan method of learning Hebrew because “they were not critical at all towards nationalistic narratives or what’s happening in the society. We wanted to shape society and not just the learner.” TINAU itself adopts a critical pedagogic approach that involves “small classes, anti-authoritarian teaching, and critical content” inspired by “postmodern linguistics.”

Interestingly, TINAU also offers classes in Arabic, one of which is a course named “Navigating Jerusalem,” which is “inherently political, partly taught while walking through the city.” Roth and the other teachers and students at TINAU emphasize the importance of postmodern linguistics and, namely, the impact it has on revealing the politics of language. As Roth told me, “Learning Hebrew, Arabic and about the cultures of this place and the peoples who call it home through a critical lens necessarily means challenging and breaking down the frameworks for education and society that diminish human potential, freedom, and equality, while raising up the frameworks for education and society that make us all more free.”

This critical pedagogic approach is also used by the London-based, TINAU-inspired language school Babel’s Blessing. I spoke with Daniel Hayeem, a Hebrew teacher at Babel’s Blessing in 2016 and a member of the Jewdas collective, who described it as “first and foremost a radical language school that seeks to be a space where languages can be taught in exciting and unorthodox ways.” Hayeem explained the school’s methodology in the following way: “Our approach emphasises critical pedagogy, inspired by the likes of Paolo Freire, where education is not simply the dictating of information to students who are supposed to be mere receptacles of knowledge passed down from on high, but rather an active participatory process involving both teachers and learners on an equal playing field. The aim, as always, is for people to learn new things in a manner that instills a critical consciousness.”

Babel’s Blessing, Hayeem says, started by asking a number of crucial questions: “Could a space be set up where Hebrew could be taught in a way that is neither wedded to the standardised, bureaucratised language that is taught in Ulpanim - and thus bound up with the Israeli state’s nation-building needs and other assorted raisons d’état - nor just another course geared towards religious training? Beyond this, what does it mean to tap into the rich diasporic history of Hebrew, divorced from the state of Israel, where it regularly interfaced with other languages, whether through the medieval Cairo Geniza or the formation of a plethora of Hebrew-influenced languages, from Yiddish to Judaeo-Malayalam? And finally, how can language learning be an act of decolonisation?”

So can learning Hebrew be a different experience if learned in a diasporist, non-Zionist context? When Hayeem hears Palestinians speak of Hebrew as “the language of occupation,” he “can only nod in agreement, for this is their lived experience of a language that was forced on them,” and when Jews say that they want to learn Hebrew in a different way, “they are expressing their critique of Zionism and interest in diasporic Hebrew culture, which very much can go hand in hand.” But when studying Hebrew in a context like that of TINAU or Babel’s Blessing — “outside of the realm of its participation in erasure and dispossession in Palestine,” as Hayeem puts it — Hebrew can become the language of those wishing to push back from within, a sort of “linguistic resistance.”

Both Roth’s and Hayeem’s answers were echoed in a discussion I had with five students taking part in Ot Azoy 2016, the London-based Jewish Music Institute’s (JMI) week-long Yiddish language, music and cultural immersion course based at University College London. One comment by Paris-raised Joshua Margulies particularly stood out. When I had mentioned that many of the activists I had researched were negotiating ways of looking for alternative ways of identifying as Jewish without Zionism, he agreed with that sentiment, saying that he prefers learning Yiddish over Hebrew and felt much more “himself” when studying Yiddish.

“When you speak Yiddish, you always think about the past, [whereas] when you speak Hebrew, you think about the present. It’s a very ‘everyday language,’” Margulies said. “Yiddish is the language which got fixated in the past with the Holocaust, and there is always this longing of going back and thinking about going in the past, in the shtetl and all of that. Hebrew doesn’t capture this longing for the past.”

Hayeem saw something similar among his students: “I find in many cases that when Jews learn Arabic, Yiddish, and Hebrew in a decolonial, diasporist context, as well as with anti-authoritarian teaching techniques, it not only correlates with them having views that are critical of Zionism but also facilitates exploring their own Jewish identities from different angles and in new, stimulating ways.”

What connects both Hayeem and Margulies is not necessarily the language spoken, although both speak Hebrew and Yiddish, but rather how that language is taught: stressing the importance of a diasporist framework. Given that so much of today’s attempts to celebrate Jewish diasporism is done in the context of a critical reappraisal of the politics of Israel and Zionist nationalism in general, the resulting opening up of a new political space, as we have seen above, can greatly facilitate the transition from a more ‘specific’ identity politics (being Jewish while rejecting Israel’s supremacy over Jewish identity) to a more ‘general’ solidarity-based internationalism (supporting Palestinians).

The very act of deconstructing Zionist hegemony is in itself an act of rebellion, as gender theorist Judith Butler, who defines themselves as both queer and Jewish, explains: “[by] showing that there are not only bona fide but imperative Jewish traditions that oppose state violence and modes of colonial expulsion and containment,” one succeeds “in affirming a different Jewishness than the one in whose name the Israeli state claims to speak.” While none of the scholars, or indeed the activists and journalists, I spoke with believe that Yiddish will claim again its centrality to (non-Orthodox) Ashkenazi Jewish life, what is evident is that an alternative radical Hebrew culture is developing out of the same frustrations with the Israeli government’s politics.

Yiddish and the politics of gender

Another point, which Margulies made during our exchange, relates to the politics of gender. He mentioned how common it was to see Yiddish associated with the female body, in contrast with the ‘strong’ masculine Hebrew body, in Israeli literature, which I would add is also present in Israeli cinema.

This opens up a new space for those resisting Zionist hegemony from a specifically gendered perspective. The growing tendency for Queer theoreticians such as Butler to link American LGBTQ opposition to the Israeli occupation with the concept of intersectionality is allowing those exploring alternative ways of being in a patriarchy-dominated space to form alliances with those exploring alternative ways of being in a dominant Zionist space, as can be observed in the growing American Jewish and/or American LGBTQ opposition to pinkwashing. As one Queer anti-pinkwashing activist and ‘Jewish Voice for Peace’ member put it, “Pinkwashing erases queer Palestinians or uses them as props for a narrative in which Israel becomes a savior while intentionally distracting from the oppression, violence and racism all Palestinians face.”

At its heart, this movement comes from a growing awareness of how, in Butler’s words, “those who are subjugated nevertheless find means for resistance. We can see such actions as attempts at what African-American activist and scholar Angela Davis described as practising “intersectionality of struggles.” While Davis was writing more specifically on the growing African American-Palestinian solidarity, one can apply the same principles to Queer opposition to Israel’s oppression of Palestinians. And one should note that this intersectionality of struggles in practice was launched in Israel itself with groups such as “Black Laundry” and “Anarchists Against the Wall” as well as, crucially, the activities of Queer Palestinians within both Israel and the Occupied Territories.

It is as if the Kulturkampf took a different, unexpected turn: rather than it being strictly about the favored language, it morphed into a larger struggle between nationalism and diasporism, both largely in Hebrew, a belated ode to the earliest Kulturkampf between the Yiddishist Internationalists and the Hebraist Nationalists/Zionists. Israeli poet Mati Shemoelof wrote in August 2016 of the growing alternative Hebrew culture outside of Israel, attributing its ascendance to diasporic culture. This discourse, Mati Shemoelof writes for +972 Magazine, “is not defined by the physical location of the writers, but rather by their consciousness, which is the product of diaspora. In the global age it is difficult to feel obligated to national borders, the borders of language, or the borders dictated to the citizen by his nation.”

This fits well with the position argued by those proposing a ‘post-Zionist’ framework, people like the Israeli-American historian Daniel Boyarin, himself an anti-Zionist, who argue that Jewish culture itself was “initially constructed in the diaspora” and can therefore recreate itself in a post-Zionist space. A diasporist framework, Butler argues, can also serve as an alternative challenge to the “hegemonic Ashkenazi definition of Jewishness” for the simple reason that “Moses, an Egyptian, is the founder of the Jewish people, which means that Judaism is not possible without this defining implication in what is Arab,” hinting at even wider implications of the diasporist framework to include Palestinians as well.

One can argue that Zionism “won” the Yiddish-Hebrew Kulturkampf. But we can see that another one is already taking place today. Rather than the inherent hostility towards the non-Jew associated with Zionism, a more inclusive attitude is being proposed by anti-Zionists and post-Zionists advocating diasporism, itself in many ways a belated ode to the concept of “doikayt.” There is a conscious effort to promote Jewish diasporist identity, which, in practice, means rejecting at least two of the four principles of Zionism as defined by Grabski: “The primacy of the Jewish community in Israel over Jewish communities around the world” and “attributing to Hebrew the status of being the main or even only national language in Palestine.” Whether the third principle, “the elevation of ethnic-religious conflicts over class conflicts,” is being challenged, and therefore linking diasporism to a more class-conscious internationalism, will depend on whether the rejection of Zionism is always coupled with an explicit politics of solidarity with Palestinians oppressed by the State of Israel. If so, this would mean the de facto rejection of Dr. Grabski’s last principle of Zionism: “the primacy of Jews over Palestinian Arabs within the borders of the former colonial mandate in Palestine.” In any case, the Kulturkampf continues.

Elia Ayoub is a Lebanese writer, researcher, and podcaster offering his observations on the Mashriq (Lebanon, Syria, Israel-Palestine) and the world from an anti-authoritarian perspective. He is the founder of the podcast The Fire These Times, co-founder of the From the Periphery Media Collective, and publishes the Hauntologies newsletter.