Word on the street is…

An article by Philadelphia shul teacher Shloyme Davidman reveals the extent to which secular Yiddish shuls were embedded in in the everyday lives and struggles of the working class.

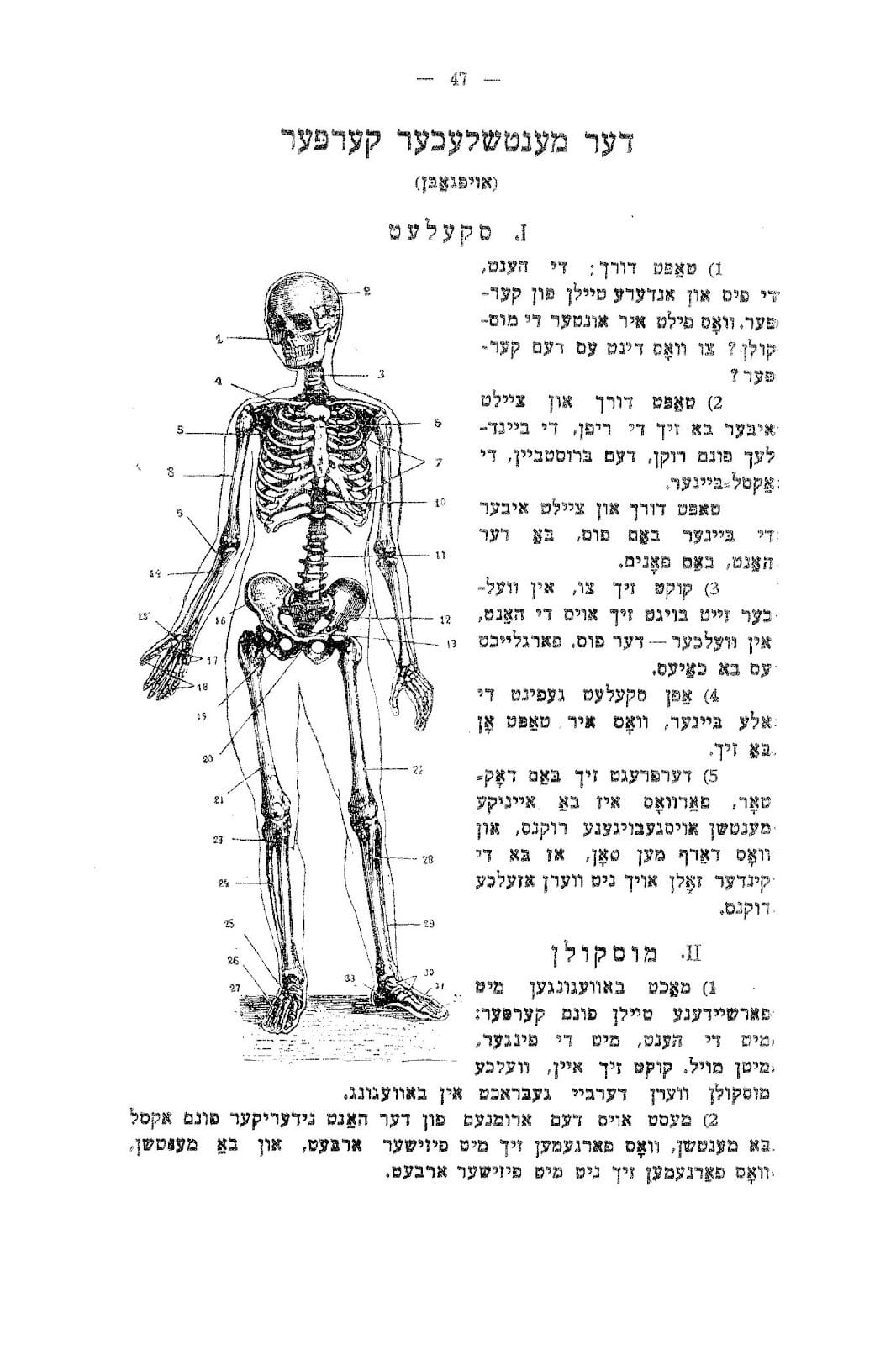

In the early 1900s, the first secular Yiddish shuls (schools) and education programs were founded in North America and Eastern Europe. In Eastern Europe, many Yiddish shuls taught the same subjects as other “national schools,” albeit in Yiddish and with an admixture of Jewish history and culture. This was especially true in the Soviet Union, where Jews were classified as a national minority group and where — despite the suppression of Hebrew — Yiddish was recognized as an official language by various Soviet Socialist Republics. Thus, in 1931, before the brutal suppression of Yiddishkeit under Stalin, over 160,000 students in the Soviet Union were enrolled in state-sponsored schools conducted entirely in Yiddish. Yiddish shul textbooks published by Eastern European and Soviet institutions like the Kultur-Lige often covered subjects like world history, health, science, geography, and math.

In the United States and Canada, most secular Yiddish shuls served, much like Hebrew Sunday Schools, to supplement students’ public school education with after-school lessons in Yiddish and Yiddishkeit. In the United States, the secular appropriation of the Sunday School format was suitable to a legal code that granted rights to Jews, not as a national minority, but as a religious group. Beginning in 1910, various mass organizations like the Jewish National Workers Alliance (Labor Zionist), the Workers Circle (Socialist), and the International Workers Order (Communist) sponsored Yiddish education programs and opened kinder-shuls (children’s schools), mitlshuls (secondary schools), and universities throughout the United States and Canada. In practice, these Yiddish shuls also transmitted their parent organizations' theories of Zionism, Yiddishism, Socialism, or Communism, that, much like Judaism and the languages of Yiddish and Hebrew, exceeded what students were taught in North American public schools. Indeed, even before they established institutions of secular Yiddish education, Jewish mass organizations like the Workers Circle and the Jewish Socialist Federation had sponsored Socialist Sunday Schools in English.

In the late 1920s, various linke (left wing) branches and shuls split from the Workers Circle and formed a loose network of “independent” Worker’s Circle branches and “umparteyishe” (non-partisan) shuls. In 1927, this milieu founded The Jewish Workers University in New York City, where linke shul teachers and labor organizers were trained. In 1930, following a convention at the Ex-Workers Circle summer camp, Camp Kinderland, the majority of these umparteyishe groups and institutions coalesced and formed a new organization called the International Workers Order (IWO). By the mid 1930s, the IWO’s Yiddish shul program had surpassed that of the Workers Circle to become the largest in the United States. At its peak the IWO enrolled around 7,000 students in its kinder shuls and mitl-shuls throughout the U.S. and Canada, and at the Jewish Workers’ University in New York.

During the Great Depression, when working-class parents could hardly afford food and clothing for their children, not to mention Yiddish shul tuition, the IWO grew its Yiddish shul program by entrenching it in the class struggle that its students, teachers, and parents were waging. Funnily enough, by adapting the Yiddish shul into a “worker-center,” where groups of all ages convened throughout the week to organize and learn, the IWO eschewed the Sunday School form for something more befitting of the term shul.

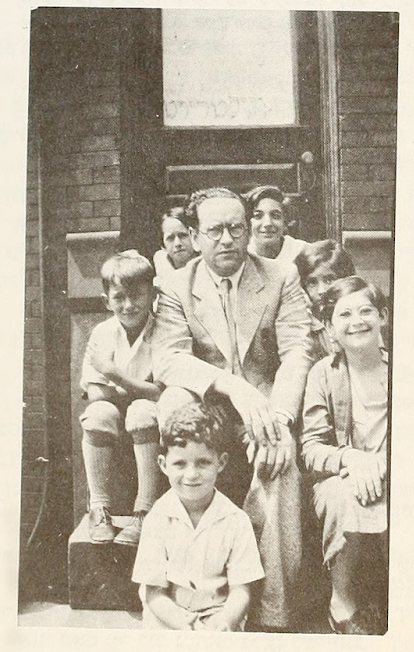

The article translated below, written by IWO shul teacher Shloime Davidman, was published in the Morgn Freiheit during this period, in March 1933. In the article, Davidman represents Philly’s IWO Shul No. 6 as the locus of a mobilization in its neighborhood against the eviction of a shul student and his family. I’ve translated the article’s title and closing refrain (in Yiddish veist shoin di gas, literally “the street already knows”) as “word on the street is…” The postscript following the translation provides further context into local struggles Davidman was discussing in his article.

As a new resident of Philadelphia, I have been especially interested in learning about the history of secular Yiddish education in this city. To that end, I have found myself drawn to Davidman’s vivid and impassioned stories, plays, and poems (!) about Philly’s IWO shuls, which strived to involve themselves, both locally and internationally, in the everyday lives and struggles of the working class. In a forthcoming article for Der Spekter, I will describe in greater detail the role that Philly’s linke Yiddish shuls played in the local class struggle. In that article, I will assess these shuls’ educational praxis, in light of various pieces of writing by their students and teachers.

Word on the street is...

(It's a street in Philadelphia - and the "reds" have holed-up there.) A report by Shloime Davidman.

(ווייסט שוין די גאַס, Morgn Freiheit, March 19, 1933. Translated by Cassie Bishop)

Seventh Street in Logan, Philadelphia, looks totally classy: clean, tidy, dressed-up with trees and lawns around the private houses. It’s as quiet on the street as it is inside the church, which stands on the corner, and the few who pass by nobly watch their steps, as to not arouse the buildings from their tranquil sleep.

In their seven good-golden years, business owners built brick houses here- little palaces, really. The world should think the people living here are millionaires, but in truth they’re toilers — toilers and well-paid workers.

When the Crisis saw such beautiful buildings, it was embarrassed to go in through the front door, so it snuck in the back. And then signs appeared in the windows, with red and black letters: "Rent," "Sale," "Rooms."

Quietly the toilers moved out of the little palaces, with their plush furniture and their radios, and went elsewhere among the poor streets and alleys downtown.

⸬ ⸬ ⸬

The Yiddish Children’s School Number 6 of the International Workers' Order moved into one of the houses, and the forces of the poor began to assemble a branch of Order number so-and-so, a communist unit, youth and children’s sections of the IWO, the International Workers' Aid, and more. The house became a worker-center.

Still, Seventh street stands quiet. People are afraid to go that way — the "reds" hang out there, the communists. They only come by the backstreets— by ones and by twos, quietly, bubbling with excitement, changing, moving, bringing newcomers. But Seventh street stands quiet.

⸬ ⸬ ⸬

Clinton, a young boy, age eleven, slinks very quietly into the shul. This isn’t his nature. His face is pale. He wants to tell us something, but he can't. Finally he spits it out: “They’ve had nothing to eat— tomorrow they’re going to throw them out on the street!”

All the children turn to him, one by one, thinking. The teacher takes questions from the class. The children organize.

⸬ ⸬ ⸬

All through the night a committee from the Shul Union runs around, from house to house: "they’re throwing a family out on the street!" In the evening the family’s house is packed with members of the Shul Union, the Order branch, and other organizations. People speak— they decide: "they won’t be thrown out!"

A committee goes to the leasing agent, who actually lives on Second Street. It’s nice and warm for him at his house. He sits in a plush chair with a thick cigar, listening to what "his" Roosevelt did to save the country. Suddenly there’s a committee at his house for him. He turns off the radio right away and plays the businessman. He flares his nostrils, smells the danger. He gets the picture in his head pretty quickly. He won’t let anyone throw a family out. You can be sure of that— he’s been an agent for 12 years, and he never threw any family out on the street. He calls the constable on the phone, then and there. The agent: “Stop the eviction!" The constable: "Yes.”

The agent actually sent his children around the neighborhood right away to announce that there would be no meeting in the house, since the agent had stopped the eviction.

Meanwhile the agent goes off to the family and whispers something in their ear. And now the family will move to some other street, discreetly…

⸬ ⸬ ⸬

But word on the street (the classy, dressed-up street) is, that if it weren’t for the Shul Union, the family’s house would be cold, they’d have nothing to eat, they’d be thrown out on the street...

But word on the street is, if you’re facing eviction, if your children are going hungry, you should report to The Jewish Children's School Number 6 of the IWO. Word on the street is...

A Tale of Two Shuls: Philadelphia’s Yiddish Shul No. 6 and Olney High.

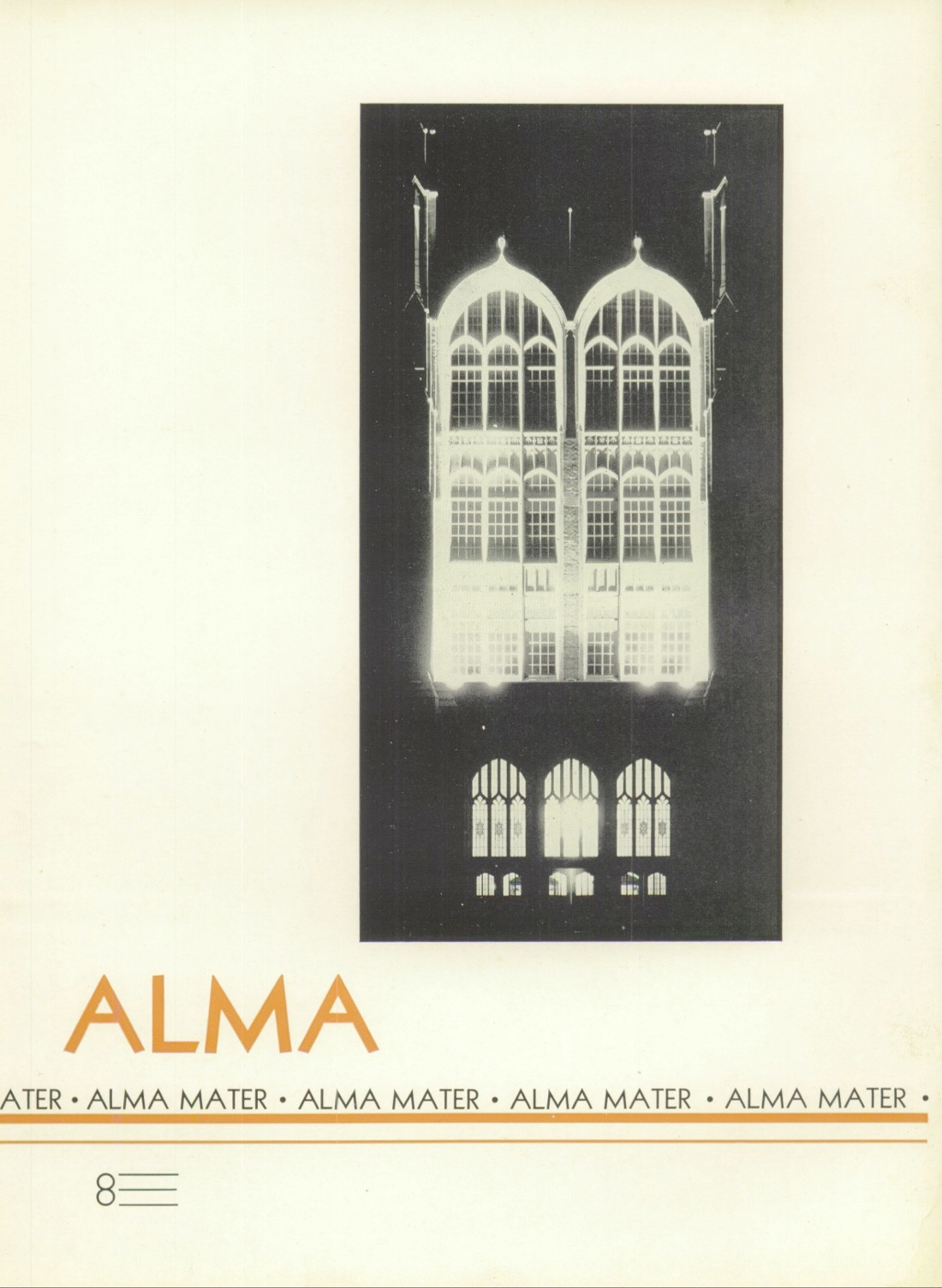

On September 1, 1928, Philly’s Broad Street subway line connected the Logan and Olney sections of Philadelphia to the city’s urban center, which lies six miles to their south. The opening of the Broad Street line precipitated a boom in capitalist investment in Logan/Olney that was bust, just a few months later, by the economic crisis of 1929, from which the Great Depression ensued. The result, as Shloime Davidman describes in this article, was a neighborhood full of expensive new buildings inhabited mainly by working-class people, including a large proportion of Yiddish-speaking Jews, many of whom were first or second generation immigrants to the United States. Among the expensive new buildings in Logan/Olney was the Olney High School, built between 1929 and 1930 in neo-Gothic style. After Olney High opened, all the students from three smaller local high schools were transferred there. In all likelihood, many students at the IWO shul No. 6. also attended Olney high.

In contrast to Davidman, who finds bitter irony in the coincidence of rich buildings and poor people, it would seem that the leaders of Olney High identified strongly with their school’s expensive, ecclesiastically-inspired architecture, given that Olney High’s silent marble stairs, empty vaulted halls, and airy cathedral windows were pictured ostentatiously in its early yearbooks. To that end, in a story published in his 1925 collection, “The War in New York,” Davidman had wondered: “Why is it that the teachers in the Yiddish workers’ shul talk about workers and revolutions, creators and revolutionaries, and the teachers in the public school talk about kings and palaces?” Indeed, the IWO shuls, like other socialist Yiddish shuls in North-America, often taught against the public school curriculum, which they interpreted as chauvinist and classist.

Like Davidman’s “Yiddish Children’s School Number 6,” the majority of North-American Yiddish shuls were established, not in purpose-built palaces, but in rented houses and appartments. Thus, true to Davidman’s account, the 1932 address of Philly’s IWO Shul No. 6 was given, in Kinder Freiheit (a special children’s edition of the communist newspaper Morgn Freiheit), as 4758 North 7th Street: a rowhome in Philly’s Logan/Olney section. Before moving to 7th street, Shul No. 6 was founded, in 1930, at 341 Wyoming St., another rowhouse in Logan/Olney.

In his semi-fictional story The Yiddish Teacher, translated into English by S. P. Rudens, Davidman writes about how one family hosted an IWO shul, among other events and organizations, in their Philly rowhouse. This was in the same period (1932-33) covered in “Word On The Street Is…”— a period of “tension, (...) unemployment, and hunger,” when "many children attended [shul] without tuition, and [the teachers] received a very reduced wage.” At the shul, the teacher Mordechai, a stand-in for Davidman, “told the children why their parents were without work, and why many people were starving.” To this, “the children asked many questions, Sammy above all others.”

“After the lesson,” Davidman writes, “Sammy often remains at school with his teacher.” Davidman continues:

Sammy has plenty of time for school. He does not have to go far to his home. He actually lives in the same building. The three-story house has many rooms, though no one lives therein. Only Sammy, his little brother, his little sister, and his parents live there.

The building is a meeting-place for all kinds of organizations for adults. Each organization pays some money into the common treasury and the house is maintained in that manner.

Sammy's parents are in charge of it. They keep the rooms clean, so that meetings may be held there, also various lectures and entertainments, and that Mordechai, too, might teach the Jewish children there.

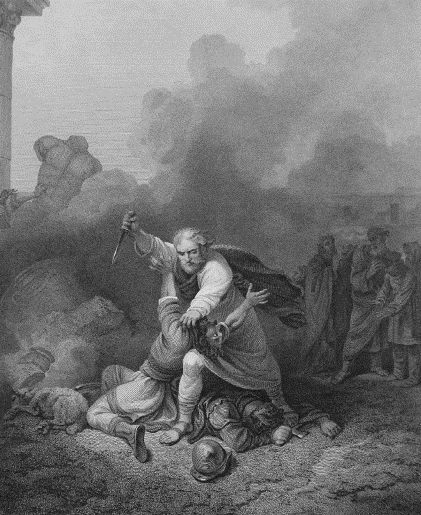

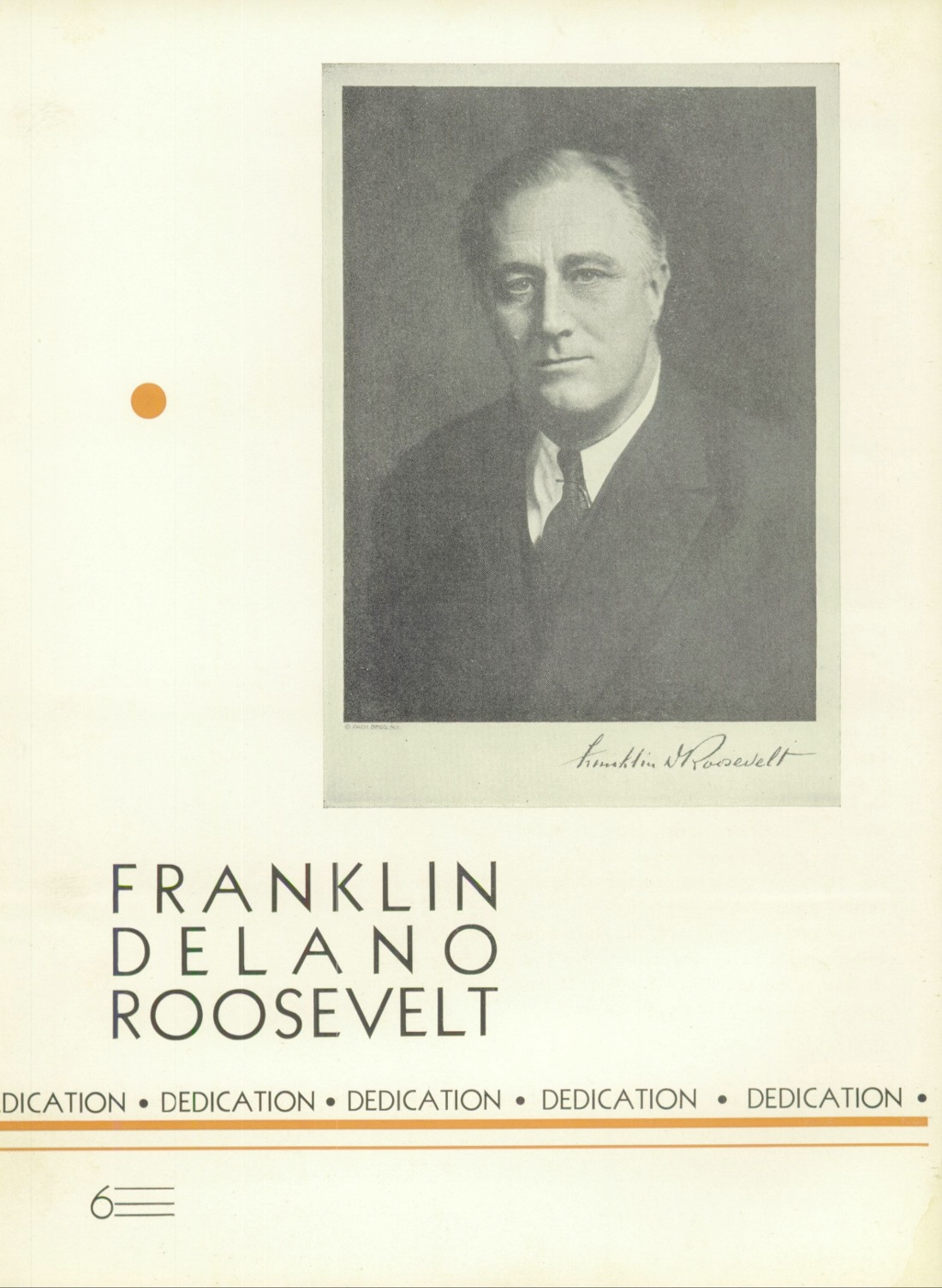

The different organizational and architectural styles of Olney High and the Yiddish Shul Number 6 reflected these institutions’ opposing political views. On that note, we might compare what Davidman’s 1933 “Word On the Street Is…” has to say about president Franklin D. Roosevelt with the words of “Dedication to F.D.R.” published just a year later in Olney High’s 1934 yearbook. In the Dedication, a group of “graduates of Olney High” thank President Roosevelt for rescuing America from the rising tides of revolutionary fervor, in which even the “most patriotic citizens” were nearly swept away. Thus, these Olney High graduates hail F.D.R. as “a new Moses (...), whose life work was to lead his people out of the Land of Egypt.”

In Davidman’s “Word On The Street Is...”, a leasing agent, enraptured by F.D.R.’s speech on the radio, gets a rude awakening when a committee of militant, working-class Jews marches on his home. Although, in the end, the agent concedes this committee’s demands and stops an eviction, he does so only to credit himself, and proceeds to displace his tenants more discreetly. In sum, while both pieces cast F.D.R. as a hero of the petite bourgeoisie, and as the peace-broker of a Jewish-coded, revolutionary rabble, only Davidman’s does so cynically. Whereas these representatives of Olney High sought to divide the working class like the waters of the Red Sea, Davidman and the IWO championed class struggle as the floodwaters in which new worlds are born. In that vein, in “Word On The Street Is…”, the workers’ boiling or “bubbling [over] with excitement” (in Yiddish, kochn zich iber) on their way to a meeting, seems to foretell a flood.

Above: Citation: 1934 Olney High School Yearbook via archive.org.